Tommy Pearson is a pioneer in the production of film screenings with live soundtracks and film music concerts. As the founder of Big Screen Live, renowned for its world-class productions in major venues around the globe, Tommy has continuously pushed the boundaries of live film events delivering experiences that are both world-class and high-impact. His latest endeavour, “The Death of Stalin in Concert”, held at the Barbican in March, showcased the exceptional score by Christopher Willis. Using Dorico as his notation software of choice, Tommy prepared the score for the live event, which was performed by the BBC Symphony Orchestra under the baton of conductor Matt Dunkley. In our recent conversation, Tommy offered insights into his involvement in the project as well as his overall approach to preparing film scores for live performance. Keep reading to find out more.

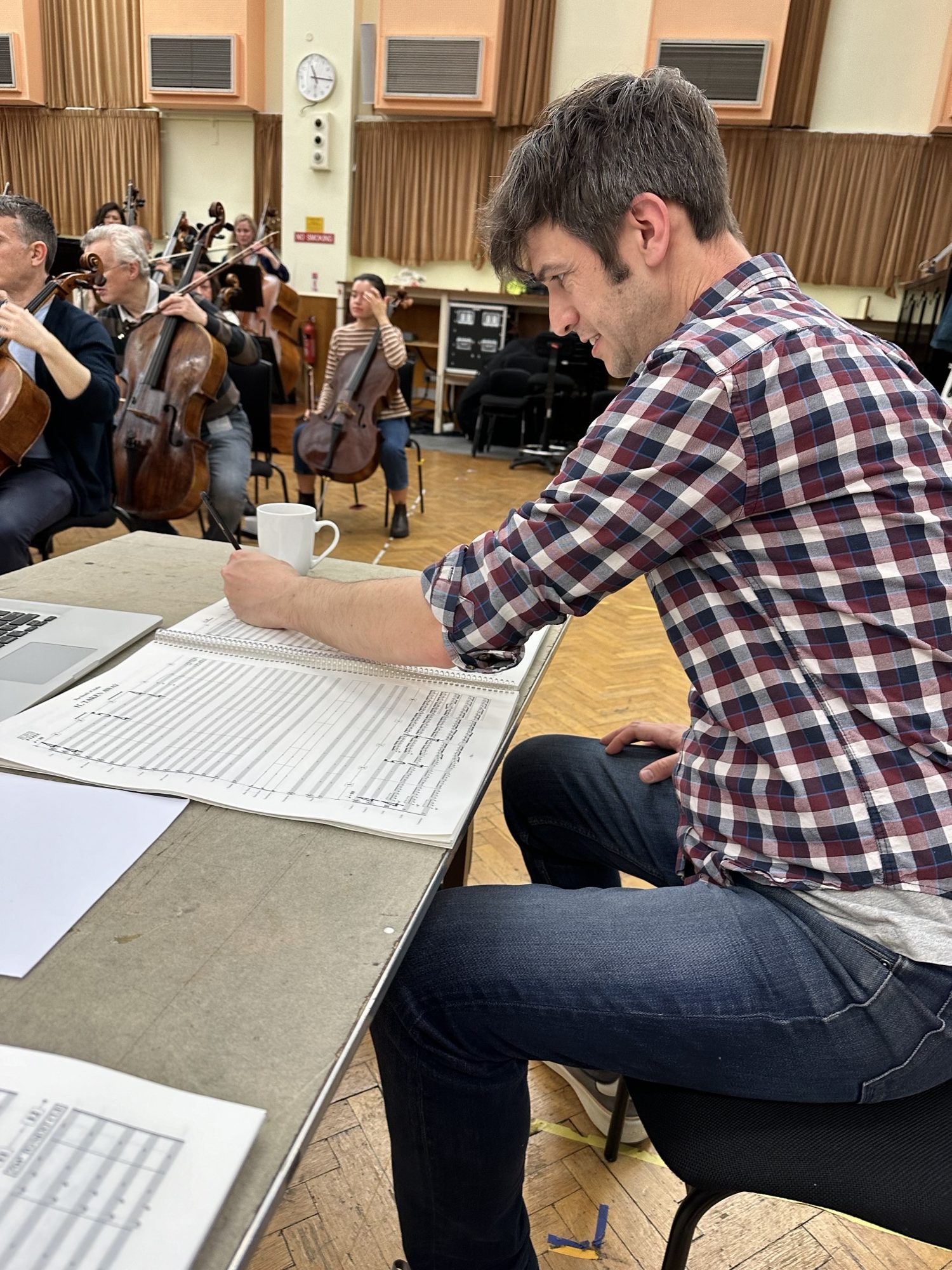

Rehearsing “The Death of Stalin” at the BBC’s Maida Vale Studios with the BBC Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Matt Dunkley. Composer Chris Willis looks on.

AN: How did the idea of creating a live score for The Death of Stalin come about, and what inspired you to pursue this project?

TP: I had wanted to do The Death of Stalin with live score for a while and when another project fell away for a variety of reasons, I was able to make a start on Stalin. Since the film’s release, I’ve been a huge fan of the film and its score and I had it on good authority that the composer Chris Willis was very nice – and he is! – so I approached him about doing it. Chris was very enthusiastic and quickly sent me all the cues from the film in PDFs for me to look at. I then started matching them to the film. So often with film music, what is in the final film and what was recorded in the sessions can be different things! Scenes get cut, directors make little editing decisions that can affect the score, and so on. So my job is to go through it all and match what I have in manuscript with what is on the actual soundtrack. Often this can be a total nightmare – one film I worked on for live performance took nine months to put together! – but Stalin was pretty straightforward. There were a few edits and changes to be made but nothing too serious.

The director of “The Death of Stalin”, Armando Iannucci, alongside composer Chris Willis, at rehearsals.

AN: Could you walk us through your workflow and process of using Dorico to prepare the score for a live concert performance?

TP: The biggest job was bringing the whole thing from Sibelius, which Chris uses, to Dorico, which I use. So, I used MusicXML files to bring it across and then got it all looking right. I’m OK with Dorico these days but there are still things I need to know – and never have much time to deal with – so I spent a very helpful afternoon with John Barron on various techniques. Things that would save me literally hours. It was fantastic. I also used a template by Philip Arthur Simmons which was incredibly useful for giving me the look and feel I needed for the score.

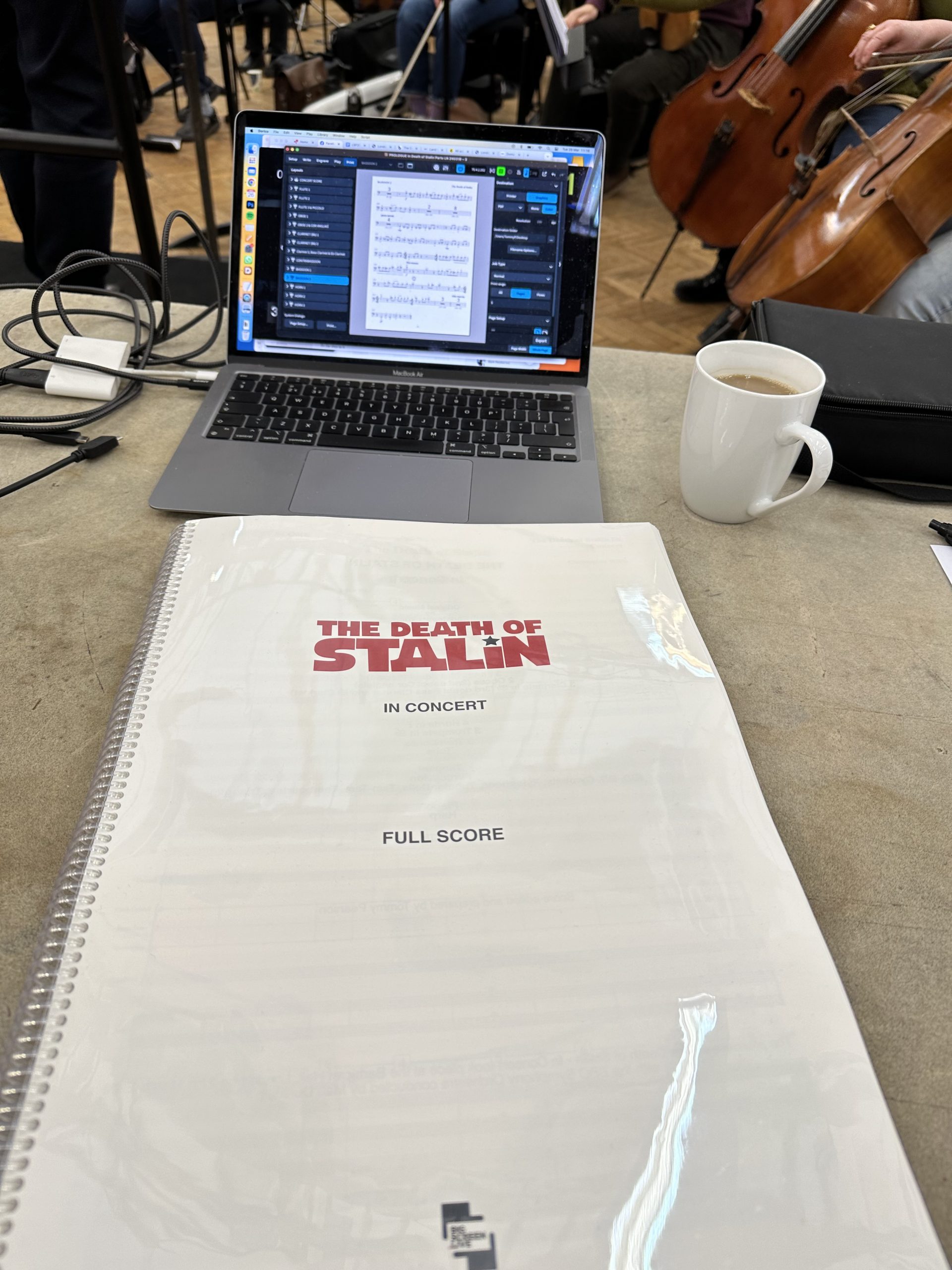

Tommy Pearson’s workstation for rehearsals: full score, plus laptop running the conductor’s synch screen and Dorico for quick revisions, if needed.

AN: How do you ensure that all necessary elements are included in the score for a live film performance, and what are some of the key considerations in preparing the score for the conductor and performers?

TP: I try and get everything into the score I need which, in the case of Live Film performance, goes beyond just the notes. I also need to include a number of things for the conductor: where the streamers will be on the conductor screen (which I also prepare); timecode at the start of each cue; some annotated visual cues if needed; and at the end of each cue, a timing that tells the conductor and players how long it is until the next cue.

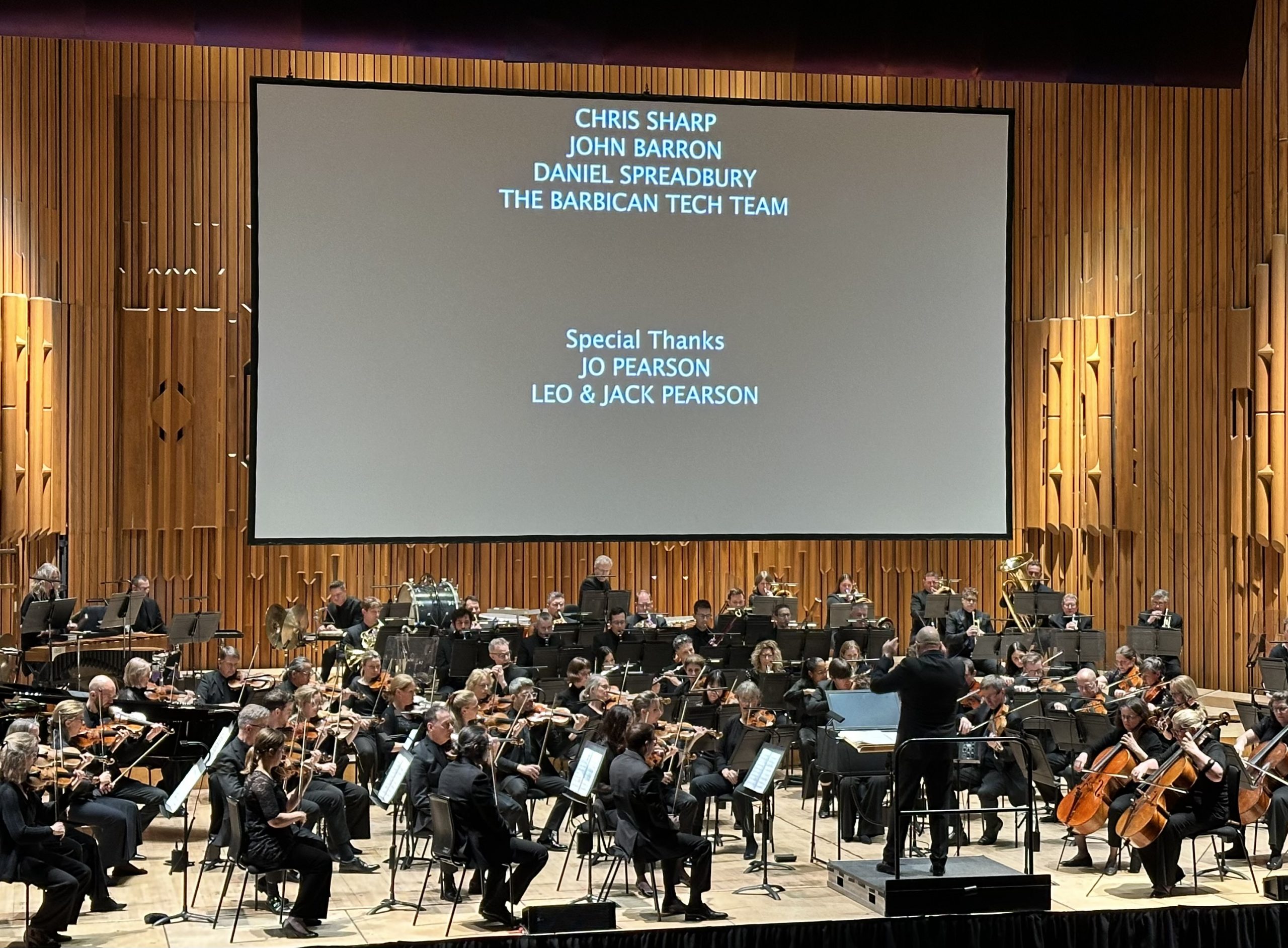

End Credits during the performance at the Barbican Hall, London, including some familiar Dorico names and Tommy’s wife and children.

Once I’ve got everything into the score I spend time ensuring the notes are all correct. I’m old-school when it comes to this and tend to do it all by looking at the score rather than listening to it. But NotePerformer helps every now and then – there’s always something hiding in there somewhere! But once I’m done, I hand it over to a copyist/editor who is brilliant at Dorico and I’ve been so lucky over the years to rely on Lillie Harris for this, who just knows how to make my scores look lovely and proper. Lillie is much busier as a composer herself these days, which is fantastic, so I used Leo Nicholson on Stalin and Leo was amazing – and quick – and never missed a thing. These projects tend to be a bit of a rush at the end of the process, so I also need someone to come in and take over, especially for the preparation of the orchestra parts because, by then, I’m having to deal with a lot of other bits of the production.

Composer Chris Willis at rehearsals in BBC Maida Vale Studios.

AN: In what way would you say that Dorico contributes to your creative process?

TP: I owe Dorico – and specifically the amazing people behind it – a huge amount. It’s not an exaggeration to say that without them, at least one of my projects would not have happened. I only started using Dorico five years ago and it was the first music software I had ever tried. I was a composer throughout my teens and studied composition at the Royal Academy of Music, but that was in the late 1980s when there wasn’t any music publication software. When I left college I worked as a copyist for a couple of years, working on a lot of film scores and musicals, and that was all with pen and paper. Then I got a job as a presenter on BBC Radio 3 and had that career. And in the meantime, the entire music industry was transformed! By the time I came back to needing to do practical music making – beyond playing timpani in orchestras, which I do every now and then – I didn’t have a clue about any software. I was aware of Sibelius, of course, but hadn’t used it. But in a way this was to my advantage when I took up Dorico because I didn’t have any of the Sibelius ‘habits’ that colleagues had talked about.

I owe Dorico – and specifically the amazing people behind it – a huge amount. It’s not an exaggeration to say that without them, at least one of my projects would not have happened.

AN: Could you share with us a standout experience from using Dorico in any of your projects so far?

TP: The first project I did in Dorico was the live version of The Great Escape, the classic 1963 war movie with its famous score by Elmer Bernstein. The only version of the score available was the original ’short’ score that Elmer used to conduct the recording sessions: a 5-line version with most of the orchestrations indicated. So, the score needed to be expanded into full score and orchestrated and I decided to do it myself and use it to teach myself Dorico. I spent a LOT of time watching Anthony’s videos on YouTube! It was a massive learning curve, but I found Dorico really intuitive and I got fluent relatively quickly – although I can see a clear difference between the first and last cues in my original files; I definitely got better through the process!

I took my time getting all the notes in and honing the orchestration, as well as matching/synching the score with the movie. And everything was going fine until about a month and a half before the premiere performance, with the BBC Concert Orchestra at the Royal Festival Hall, when – unexpectedly – my wife gave birth to our twins two months early! Because they were so small, they had to be in hospital for a month and of course I really needed to be around for all of that, so I was suddenly distracted by the most important moment in my life, instead of working on the Great Escape score. Enter, stage left, Lillie and Daniel at Dorico. I took some time off visiting the hospital to go to the Dorico offices in a panic and ask for their help getting the score together. Lillie was amazing and took everything I’d already done and made it into a good-looking score and prepared the parts, while I prepared the conductor screen cues (and complicated process at that point) at 4am every day before going back to the hospital. It was a crazy time, and exhausting. But Dorico saw me through it!

I’ve done all my projects on Dorico since then and each update has had something that’s improved my workflow. Two of the projects, Scott of the Antarctic and The Piano, have been published by big publishers (OUP and Chester) and it’s nice that Dorico is no longer seen as a newbie by them, although they took their time!

AN: Looking ahead, do you have any future projects where you plan to use Dorico, and if so, how do you anticipate it enhancing your workflow or creative process?

TM: I have some exciting projects coming up this year and next and will, of course, be using Dorico in all of them when I need it. I have a really reliable group of brilliant people to help me prep things now. And I enjoy being a Dorico evangelist. I’ve never used anything else, so I can’t compare it to another program, but all I know is that Dorico helps me create the projects with speed, efficiency and elegance – and its customer care and support is absolutely second to none!

Dorico helps me create the projects with speed, efficiency and elegance – and its customer care and support is absolutely second to none!

AN: Thank you very much for taking the time to talk with me, Tommy.

A couple of years ago, we featured Tommy Pearson once again in our Dorico Showcase series, highlighting ‘The Piano Live’ with the London Contemporary Orchestra. If you want to read more click on the link below: