Alessandro Grego is an Italian composer who recently won the Penderecki Composers’ Competition with his music composition El mar de l’eterno, among a total of 94 scores that were submitted to an international jury by composers from across the globe. In a conversation with me, Alessandro shared some insights about his winning music piece and the inspiration behind it, explaining how he relied on Dorico music notation software for both composition and printing, while shedding light on the specific features of Dorico that helped him throughout his creative journey.

AN: Hi Alessandro, can you tell us a bit about yourself and your background as a composer?

AG: I am an Italian composer, born in Trieste in 1969. I was introduced to music at an early age due to my mother being an opera singer. I have always thought of music as a means of creative expression and I began composing at the age of six, self-taught. I have always been interested in all musical genres, but always preferring instrumental music over songs and the pop genre which I have practically never frequented. Around the age of 18, after I would have played jazz, I approached contemporary classical music and deepened my study of composition even though I had already been writing by hand for several years. At the age of twenty, I transitioned to composing music on the computer, using the first software available in 1989. Thanks to the computer and fortunate encounters in the world of avant-garde music, I also undertook the study and practice of research electronic music and computer-assisted composition. This also led me to create works where music is the creative result of the sonification of astronomical or genetic data. In university, I studied musicology because of my particular interest in Franco-Flemish polyphony.

AN: You recently won the Penderecki Composers’ Competition in Poland, congratulations! How does it feel to receive such recognition for your work?

AG: When the president of the jury Joanna Wnuk-Nazarowa announced my victory on stage, I was so amazed and incredulous that I almost didn’t understand her words. The quality of the other finalists’ compositions was so high that I never expected to win. I was moved but above all confused and incredulous.

AN: Can you share more about the composition that won the competition? What was the inspiration behind it?

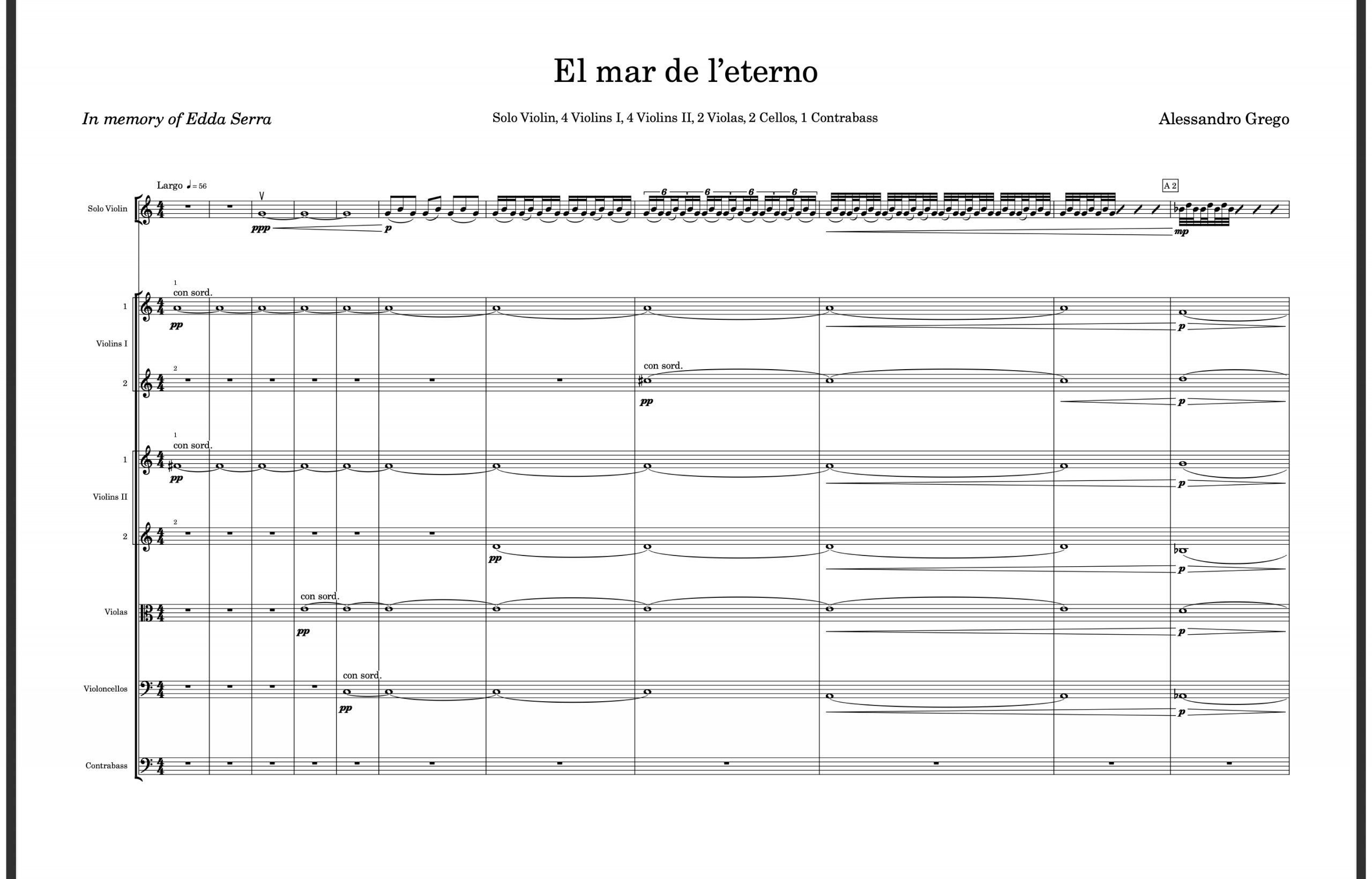

AG: The piece is a concerto for violin and chamber string orchestra titled El mar de l’eterno. While teaching harmony to a young violinist student, I explained to him how the interval of third, which is the basis of tonal harmony, can actually lead to the formation of chords that can go outside the tonality. With this idea in mind, and as an example, I started writing the concerto, thinking and hoping that one day my young student could play it. Then once completed and, thanks to Dorico, listening to a virtual simulation of it, it reminded me of another piece of mine written many years before and inspired by a poem by Biagio Marin; so I thought of naming this concert of mine after a collection of poems by Marin and dedicating it to the memory of Edda Serra who, in addition to being a literary critic and profound connoisseur of the poet, was also a dear friend of mine who recently passed away.

El mar de l’eterno: the winning score by Alessandro Grego, composed in Dorico

AN: You used Dorico both for composition and printing scores/parts. How has Dorico influenced your composition process, and what features did you find particularly valuable?

AG: As I was saying, I stopped using pencil and paper to write music back in 1990. Since then I have directly transferred the musical ideas that formed in my mind, or while improvising on the piano, onto the electronic staves displayed by music notation software.

The Dorico flow system was invaluable for organizing these ideas. However, what I found particularly useful, and it appears exclusive to this software since its inception, is the way it handles divisi strings. The harmony of my piece required the strings to split at various points, and having used other software in the past, I know how complicated this can be, especially when preparing the parts. I must say that the orchestra had no trouble reading the parts I provided, even the divided ones, which Dorico extracted from the score in the blink of an eye.

AN: Can you elaborate on any specific challenges Dorico helped you overcome in the composition of your winning piece?

AG: Despite not having participated in many composition competitions in more than 30 years of musical activity, probably less than five, I know from experience that certain juries are sometimes influenced by the graphic aspect of musical writing. Often, composers who still use manual notation show a certain distrust towards computer-written scores because they think that certain graphic limitations or certain shortcuts such as copy-paste lead to a poverty of musical content and a brake on the imagination. Aware of this, once I had composed and laid out the score using the default “Bravura” font, with one click I created a version with the “Petaluma” font to imitate or get closer to manual writing, and for the first time in my life I sent a score written in this way to a composition competition. I believe, and hope, that this did not influence the jury, but the work was selected among the 94 received.

AN: Have you used any other music notation software in the past? Are there specific tools or functionalities in Dorico that you find enhance your efficiency as a composer?

AG: I started writing with Finale 2.0 way back in 1989. I worked as a composer and copyist for various publishers with this software until 2010, then moving on to Sibelius 7 and continuing with its updates until the release of Dorico 2.0, despite having purchased Dorico already from version 1.0. What struck me immediately about Dorico, apart from the reasoning that I preferred new software with a young kernel, solid and full of potential compared to a mature one that brought with it limitations that would never be corrected, was the possibility of writing amensural (no bars nor measures) then decide at a later time the meter or meters to apply, and the ease with which this was implemented. This gave me the opportunity to concentrate on the melodic sequence regardless of the meter and vice versa, without losing valuable information and wasting time. This feature, already present exclusively in Dorico since the first version, was decisive for me.

What struck me immediately about Dorico(…), was the possibility of writing amensural (no bars nor measures) then decide at a later time the meter or meters to apply, and the ease with which this was implemented. This gave me the opportunity to concentrate on the melodic sequence regardless of the meter and vice versa, without losing valuable information and wasting time. This feature, already present exclusively in Dorico since the first version, was decisive for me.

AN: For aspiring composers, what advice would you give them, especially in terms of using technology like Dorico in their creative process?

AG: First of all, as an exercise and as a study of both music and to practice the software, I would recommend copying a lot of music from manuscripts or already existing editions: I recommend starting as a copyist. The great classical composers of the past copied much music as students, both to practice calligraphy and because manuscripts were rare and precious.

My own musical calligraphy teacher taught me the basics of beautiful and correct musical writing and I remember that when I brought him the first scores written on the computer he made me correct almost all the curvatures of ties and slurs, especially those that ended the system: with Dorico today this is no longer practically necessary, because it is a software designed by musicians for musicians, but the situation in the nineties was very different.

As for the creative side of the composition, I would say that if you are used to writing the first drafts or even the entire composition by hand, on the piano, and then copying it onto the computer, go ahead like this, but in my opinion this is not necessary, it can be composed directly in Dorico. And if you don’t have multiple screens or very large screens to view a complete orchestral page, the use of the tabs and the various layouts and the filter for the instruments certainly helps your visual memory in the creation of your piece: when I started , I wrote orchestral works on nine-inch monitors and without all these possibilities.

AN: Would you like to share with us what you will be working on next?

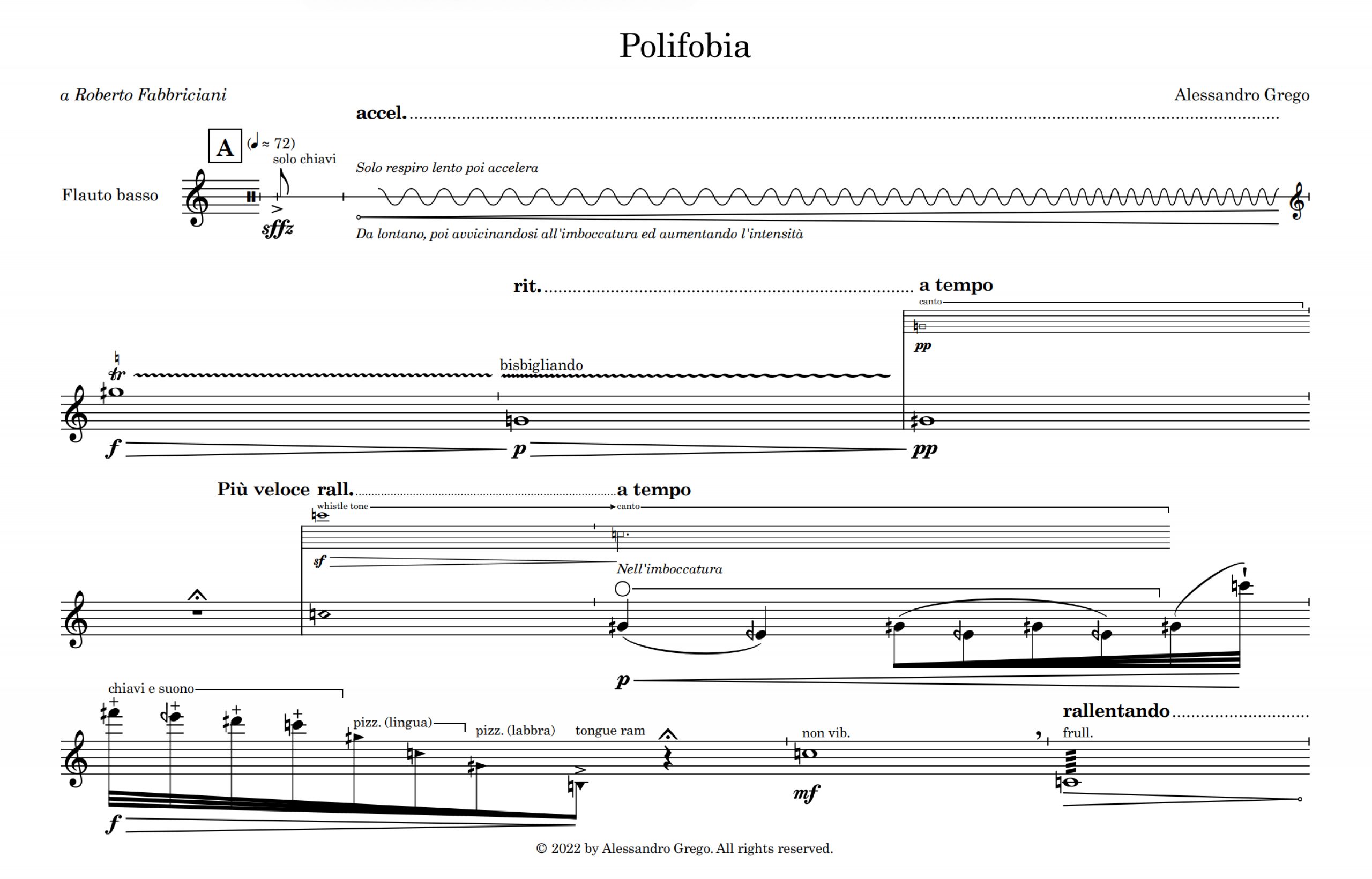

AG: I have several projects on the table but most likely I will follow up on a piece for bass flute and electronics that I wrote for Roberto Fabbriciani, titled Polifobia. It is an experimental piece that uses almost exclusively the extended techniques of the flute and I must say that Dorico has not abandoned me even in the use of contemporary musical notation. This demonstrates that this software is not only designed for tonal music but can also be used for the most extreme avant-garde languages: do you want an example?

To find out more about Alessandro and his work visit his website here.