This post is part of a series that aims to shine a light on projects in which Dorico has played a part. If you have used Dorico for something interesting and would like to be featured in this series, please let me know.

George Mpanga, better known as George the Poet, is a spoken-word artist, poet and rapper whose podcast for the BBC, Have You Heard George’s Podcast?, won a Peabody Award honouring excellence in storytelling in 2019. Recently returned for its third series, styled as Chapter 3, the ambitious podcast has included live music played by members of the BBC Concert Orchestra. George has also recently staged a live concert at the Barbican in London, with the BBC Concert Orchestra live on stage. Dorico played a pivotal part in bringing both the podcast and the concert to life, with orchestrator Evan Rogers working closely with composer Benbrick and George himself to make sure everything ran smoothly.

Evan is a graduate of London’s Royal College of Music, and in addition to being an in-demand orchestrator, he’s also a successful big band arranger and conductor, with many similarly high-profile projects under his belt, working with games publishers Blizzard, Activision and EA on games such as Battlefield: One, as well as on TV and film projects aired across Netflix, Apple TV, HBO and UK broadcasters Channel 4 and the BBC. I sat down with Evan to find out more about this project, and helping to bring George’s vision to life.

Orchestrator, arranger and conductor Evan Rogers (photo: Matt Nalton)

DS: How did you first get involved with George the Poet?

ER: I was brought on as orchestrator by Benbrick (Paul Carter) who is the producer and composer of the podcast. When he explained that the BBC Concert Orchestra would be doing 3 days in Abbey Road Studio One to record Chapter 3, we both thought how exciting that was as podcasts don’t usually get that kind of opportunity. I had heard of Have You Heard George’s Podcast? previously and then went back to listen to past episodes to get a flavour for the music and it was so eclectic. You’d have sweeping orchestral themes, tense underscore, R&B, pop, grime, and a host of other musical influences. The music is so intertwined with George’s message and delivery and Benbrick is so skilled in navigating the listener through the stories with the way he writes, to be a part of bringing that to life with the orchestra was very exciting.

DS: At the start of July, George was live on stage at the Barbican with an ensemble of 12 players drawn from the BBC Concert Orchestra. Firstly, it must have been great to be back in a concert hall with live musicians! How did it feel?

ER: I think after the year we’ve had for live music, there was definitely an air of excitement about it all! Pre-pandemic you’d turn up at sessions and there would be a quiet chatter of players talking about their mortgages – there’s excitement, but also a sense of routine about it. This time you could tell everybody just loved being back to making music in person again. After the Abbey Road sessions came a Barbican show and I remember sitting with Benbrick in the first rehearsal marking up the score and commenting on the blend and energy from the first downbeat. Most of the players had played in the Abbey Road sessions so knew George and his work prior to the show. They also play together a lot as an orchestra of course, and Charles Mutter led from the violin so it was definitely an intimate experience. You couldn’t tell anybody had had any time off! It really felt like a true collaboration and conversation between George and the musicians.

DS: George has a background as an MC, of course. Is there a strong improvisational element to the music?

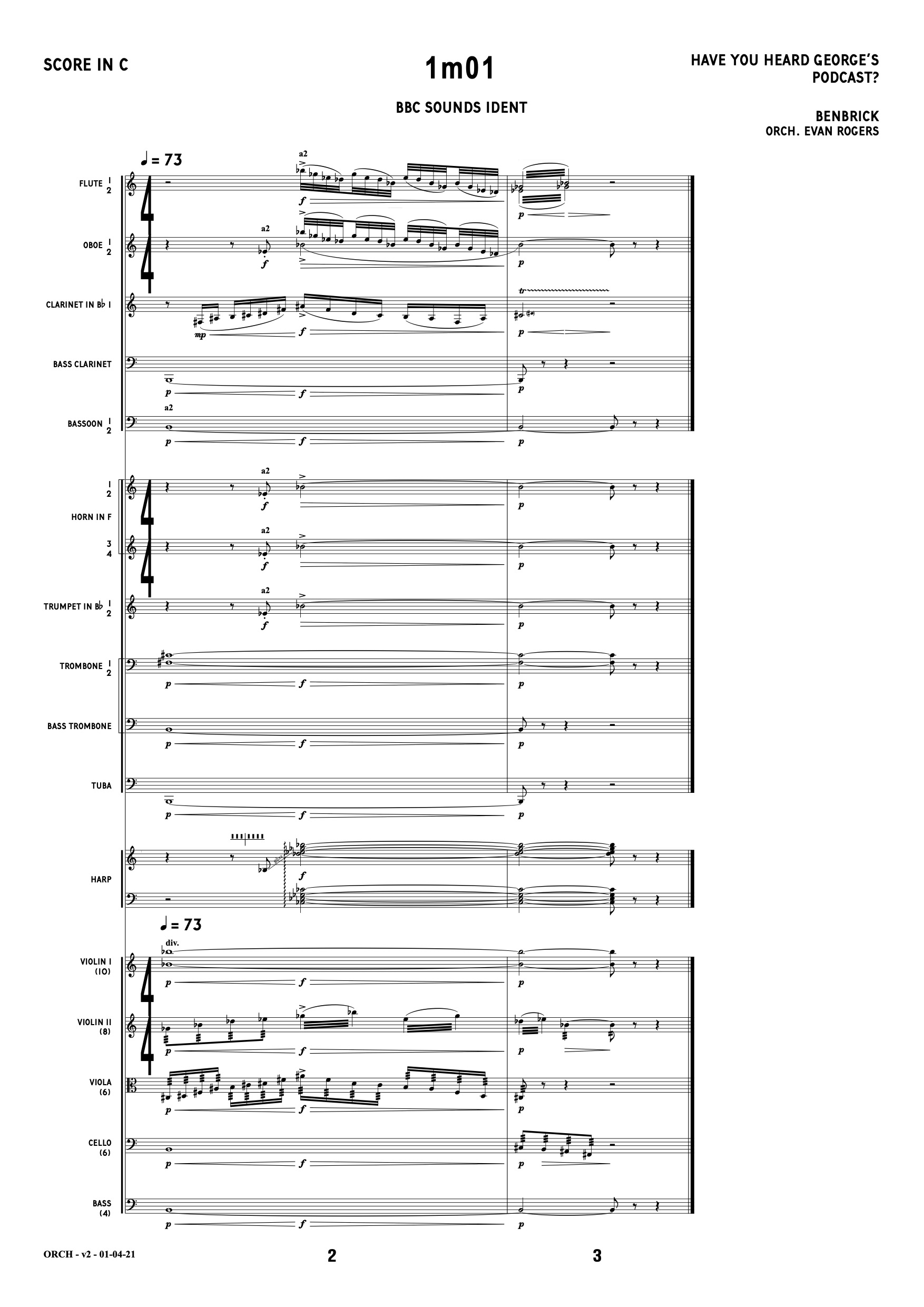

ER: There were definitely moments in this Chapter where we went down the aleatoric or textural route. There were definitely moments in this Chapter where we went down the aleatoric or textural route, but by the time we got to Abbey Road, George’s words were locked and the music was would be fit around them. The improvisation was mainly in how the musicians played, and this was something I was able to go through with Benbrick beforehand. This meant I was able to suggest opportunities for things that samples can’t do, or that he might not have conceived of doing until live players were involved. We worked on a few textures that called for musicians to interpret the aleatoric notation, most notably on some horror music which became Episode 22. Then, we created some textures out of harmonics, tremolos and extended techniques like flute harmonic glissandi and found that these were great as beds of sound that allowed George to shine over the top of – you can hear those in Episode 26. It was a really rewarding part of the process to turn up on the day and try and tweak these custom textures that can only be achieved with great live players like the BBCCO.

George the Poet in Abbey Road Studio One (courtesy BBC Sounds)

DS: The third series of George’s podcast started a couple of weeks ago. I understand you recorded some of the music for that in advance. Can you tell me about that?

ER: We did three days in Abbey Road Studio One in April. That was challenging due to social distancing as all projects were then. We had strings on two days and then wind and brass on the third day. Maintaining consistency across the three days was part of my role as orchestrator, as well as planning the sessions and being on talkback to Tom Kelly, the conductor. There’s lots of stuff in this new season that was recorded at Abbey Road and everything went smoothly. The energy in the room was fantastic. It was one of the first large sessions with the BBC Concert Orchestra done this side of lockdown and it was such a positive, collaborative atmosphere. The whole team had really pulled out all the stops and many moving parts are needed to make a session run smoothly, from great parts and accurate scores to well-prepped Pro Tools sessions. We found some sessions to go so well we could try out extra ideas and in breaks, Paul would ask me to orchestrate something quickly for us to try when the players returned, so there was a sense of real live music-making that responded to the actual players in the room. In one notable case, we loved the sound of the principal bass, Dominic Worsley, so much I scribbled a specially handwritten part for a bass solo while the players got coffee and we loved how it sounded – you can hear it in Episode 26!

Music on the stand ready for recording (courtesy BBC Sounds)

DS: Were any features of Dorico particularly helpful as you worked on this project?

ER: Too many to count! I used Dorico both on the studio scores and then for the live Barbican show. In the studio, we orchestrate from MIDI provided by the composer and having multiple layouts, one for my MIDI sketch and one for the final score is very useful. I then use multiple tabs to work from the sketch into the final score. Doing that means the sketch is always there in the file, in another layout, for reference at the session – I don’t need to hide staves or mess about with multiple files for each cue. I can even drag MIDI files directly from Cubase into the Play window for them to appear on staves in Dorico, which feels like magic to me. There was also an instance where I needed a transposing score with bar rests in (my studio scores are in C as is standard and have no bar rests) and it was as easy as adding a new layout with layout options and could keep everything in one file to minimise errors. I also use another layout for my copyist, Tristan Noon, to work directly from so I can leave notes there without it affecting the full score. Finally, for the studio, certain things are built in that are just so useful like filling the page with blank staves on parts, dynamically updating cues, built-in trill interval auxiliary notes, and of course, the massive game-changer, condensing.

For the live show at the Barbican, I used flows extensively. The whole show was done in one Dorico file with multiple flows for each piece. I could indicate when the orchestra was to tacet for a piece, whether it was to track or whether they should play on cue and include vamps, safeties, and all other common theatre devices too. In rehearsal, the players sightread the entire show top to bottom without navigation errors the first time. To get a similar result using anything else would have taken hours more and multiple files that need to be stitched together.

Musicians recording in a socially distanced Studio One (courtesy BBC Sounds)

DS: You work on all kinds of music, across film, TV and games. Do you have any interesting projects coming up?

ER: There are already talks about the next stage of Have You Heard George’s Podcast? which is exciting! I’m a contributing orchestrator for a variety of projects and have just finished Distant, a feature film out next year as well as currently finishing up some other film and TV jobs that are due for release later this year. Now that everything is opening back up, I’ve just finished conducting an album of video game music arrangements and have quite a few conducting gigs lined up, particularly for artists and songwriters. I’m also currently orchestrating for BAFTA and Ivor-Novello-nominated games composer David Housden on his upcoming projects as well as orchestrating a new musical, Colony, by Matt Nalton and Will Tudor, so lots of irons in the fire at the moment!

DS: Thanks for taking the time to talk to me, Evan!

If you’d like to find out more about how Chapter 3 of Have You Heard George’s Podcast? was put together, there’s a great article and short video available on the BBC web site. To listen to the podcast itself, you can find it on BBC Sounds. To find out more about Evan’s work, visit his web site. If you’re inspired to give Dorico a try yourself, you can download a trial version from the Steinberg web site, or try the iPad version free from the App Store.