The guzheng is a Chinese plucked zither that has existed for thousands of years, with the oldest known example dating from perhaps as early as the fifth century BC. This ancient instrument has a beautiful and distinctive sound, and is also the progenitor of many other instruments, including the Japanese koto. Composer Michael Gordon Shapiro, who has turned his considerable talents to music in almost any genre you might care to mention – with projects spanning the concert hall, theatre, cinema, TV, and games console alike – has developed a long association with the instrument, and virtuoso Su Chang. Michael’s latest work pairing the guzheng together with western instruments is a chamber piece for guzheng and string quintet, originally set to be premiered in 2020, but delayed by the pandemic until 2022. I caught up with Michael about this work to find out more.

DS: This is the latest in a series of pieces that combine the guzheng with western instruments. How did you >come to start writing for the guzheng in the first place?

MGS: Believe it or not, I answered a want ad. It was in Craigslist or The Recycler or somewhere else you normally wouldn’t expect to see a call for composer. A producer-composer named Victor Cheng wanted a composer with experience writing for both Western and Eastern instrumentation. I had recently finished a video game score which melded Korean instruments with live orchestra, giving me a on-point demo. Victor and I hit it off quickly, and I was brought aboard.

My first project was a concerto for guzheng and orchestra. It was programmatic, with a specific storyline that Victor had created. The experience was a bit like scoring a film but without visuals. We premiered the piece in Los Angeles in 2009, then produced a slightly modified version with the YMF Debut Orchestra a year later. Since then the piece has been performed a number of times around the world, including in Beijing with the China National Orchestra.

Composer Michael Gordon Shapiro

DS: How is music for the guzheng normally notated in its native China?

MGS: Western notation is used as well as a number-based system called Jianpu. The latter uses numbers to indicate pitch, and a system of diacritical markings to indicate duration, ornamentation, and other aspects of performance.

DS: Are there any special considerations you have to make in terms of tonality or tuning when combining the guzheng with western instruments?

MGS: The guzheng’s movable bridges allow easy adaptation to local tuning preferences. Guzhengs are typically tuned pentatonically, with “in-between” pitches accessible via string bends. But they can also be easily and flexibly retuned, unlike a piano. If you’re daring, you can pick different tunings for different octaves and create a sound very distinct from the traditional folk-pentatonic palette.

DS: Have all of your pieces for guzheng been written with a particular performer in mind? I understand your concerto was written for virtuoso Su Chang: has she always been the guzheng performer in your mind with each of these works?

MGS: To date Su Chang has been the originally intended performer in my guzheng works. I’ve learned her capabilities and definitely tend for them, particularly during cadenzas and other demanding passages. It’s a privilege to be able to compose for a virtuoso — and also fun, because you can anticipate dazzling the audience.

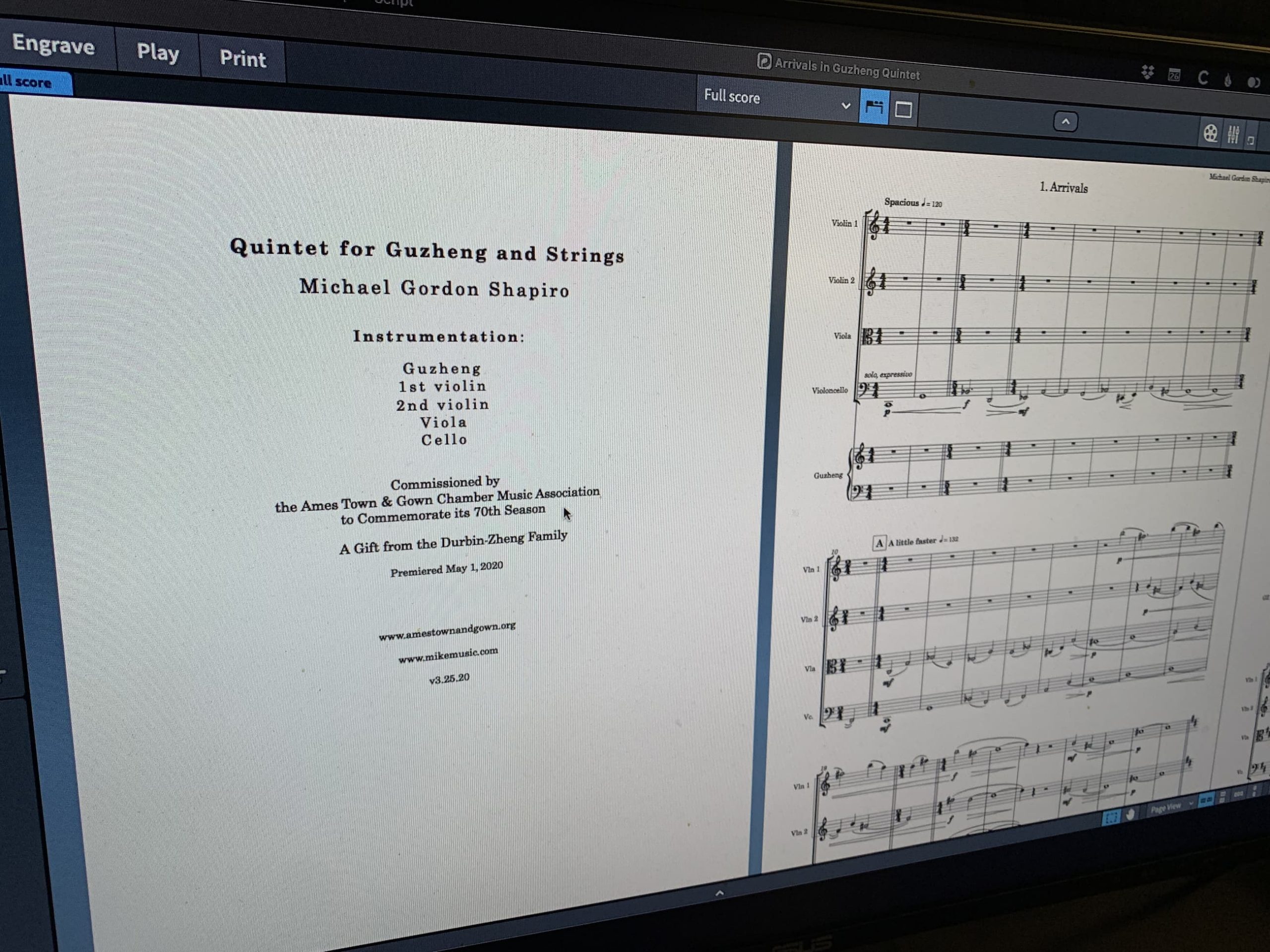

My latest piece is for guzheng and string quintet, commissioned by the Town and Gown Chamber Music Society in Ames, Iowa, back in the good old days of 2019. We initially had Su Chang in mind as soloist, but when the coronavirus pandemic made it impossible for her to travel from China, we reached out to Hui Weng, a guzheng expert who teaches at the New England Conservatory. Sadly, as we know, the pandemic then arrived in earnest. The premiere was postponed til 2022.

Guzheng virtuoso Su Chang

DS: How have you found working with Dorico when preparing your latest quintet?

MGS: It’s been a delight. I’ve been using Dorico since arguably before it was was fully usable! One of my favorite features is the ability to aggregate multiple flows (which in this case represent movements) into a single project. That seems like a pedestrian feature, but its impact is profound and strangely calming. There’s no more jumping around among project files, wondering if they’re using the same margins or sound sets, and so on. All the music is unified and feels effortlessly available. You can have alternate versions or even idea fragments, all residing in the same workspace. I’ve taken to aggregating more and more music this way: for example, all the songs in a musical or the cues in a film score.

Another calming aspect of Dorico is the segregation of music input and formatting. At first I thought this was needlessly complex, but I’ve come to appreciate it. No more trying to move a note, accidentally dragging a staff, and creating a yawning chasm between two systems.

One of my earlier guzheng and orchestra pieces was written in a different notation package, and I actually took the time to import it into Dorico. Not out of dire necessity; just because I prefer working in Dorico’s environment.

DS: In addition to your concert music, you do a lot of work for video game music, as well as writing music for film and TV. Have you been working on any interesting projects in the media music world that you can share?

MGS: I’ve been putting the finishing touches on a score for a lovely and unique game called Dice Legacy. The game has a somewhat Northern European look, which inspired me to bring aboard a Nyckelharpa player named Mats Wester. The instrument has such a lovely raw and expressive sound, and I loved blending it with the familiar Western orchestra. (You may see a pattern here.) On the musical theatre front, I’m about to launch the premiere of a new family musical called Gideon and the Blundersnorp. I’m particularly excited about this because it’s part of a return to live theater that is long overdue. Dorico has been my notation tool on all of the above.

DS: Thanks for taking the time to tell us about these projects, Mike!

If you’d like to find out more about Michael Gordon Shapiro and his music, visit his web site.