This post is part of a series that aims to shine a light on projects in which Dorico has played a part. If you have used Dorico for something interesting and would like to be featured in this series, please let me know.

Although live music has been decimated by the Coronavirus pandemic in 2020, there is hope that concert halls and other arts venues will once again be filled with music in 2021. But what will we as concert-going audiences emerging into the post-Covid world be listening to? If the team behind a new Arts Council-supported venture, Flip the Stem, have anything to do with it, more of the music we hear will have been composed by women and people of colour. Flip the Stem is the brainchild of Nadim Jauffur, who is an Assistant Music Librarian at the BBC Philharmonic and has seen first-hand the practical difficulties in bringing music from under-represented composers to live performance. Together with his colleague Jenny Espin, who also works as Assistant Orchestra Manager at the Hallé in Manchester, Nadim is producing beautiful new performance materials in Dorico and making them freely available, together with live recordings, to help get this music onto the stage once again. I recently caught up with Nadim to find out more.

DS: Can you tell me a little about why and how you started working on Flip the Stem?

NJ: I finished my master’s degree at the University of Manchester last year and whilst I was there a number of us would go to orchestral concerts and often whine a bit about the lack of diversity in programming. It just seemed like quite a simple matter – to us – of taking a stand and programming more composers. Then, before I finished my degree, I started working at the BBC Philharmonic as an Assistant Music Librarian. Not only did this provide me with the opportunity to switch to Dorico, but my boss is a really knowledgeable guy when it comes to notation software, music publishing, etc. and I’d pick his brains about it quite a lot. It became apparent that there were actually a lot of very practical difficulties that arose when programming lesser known composers.

DS: Could you say a bit more about the nature of those practical difficulties? Is it primarily about the quality or availability of performance materials, or something else?

NJ: I think the core problems are, as you highlight, availability and quality. If I want to learn a Chopin waltz, I can get the full set by an established publisher like Henlé for less than £20, but as soon as I look at lesser-known composers the prices soar and the quality is often tenuous. I saw someone looking for Florence Price’s Clouds recently and they couldn’t find it for any less than £60, and that’s a piece by a composer on the more popular end of lesser-known, with several recordings for reference. It’s asking a lot of performers to take these financial risks, especially when they can’t even hear the pieces before purchasing the sheet music. Of course, publishers end up charging more for lesser-known composers’ works to justify the cost, so it becomes a kind of positive feedback loop as well.

Coming back to the Chopin waltz though, let’s say I don’t even want to buy that. It takes me less than a minute to hop on to IMSLP, and for pieces that popular I’m immediately spoiled for choice. Even if we look at composers like Liza Lehmann or Amy Beach, who are kind of in that sweet spot of being in public domain but still recent enough to have slightly more modern, usable sheet music, a lot of their pieces are still tucked away in libraries around the world. People often scan the scores for IMSLP, but not the parts, and it seems like a small issue, but if you’re a performer you’re probably going to disregard any pieces you can’t find parts for.

Flip the Stem co-founders Jenny Espin and Nadim Jauffur

DS: Flip the Stem is designed to help smooth away some of these difficulties. How did you get started on the project?

NJ: So I got more and more into the music copying aspect of the work and decided I wanted to do it as a job, and I thought I’d build up an early portfolio by making up orchestral sets of some public domain pieces by marginalised composers to distribute freely and encourage performance amongst smaller orchestras, etc. Then the pandemic hit, and it really forced me to change my approach – orchestral work was suddenly a no-go, no-one was exactly jumping at the chance to take any risks with their programming and everyone had just lost the pretty much guaranteed income that a whole year of programming just Beethoven was going to bring. After a bit of planning, I hit up a good friend of mine, Jenny Espin, who works at the Hallé and asked them if they’d like to help me launch this new project which I hoped, with funding, would be able to provide work to a lot of freelance musicians and still accomplish the fundamental goal of encouraging performance of marginalised composers. We figured it made a lot of sense, because convincing an orchestra to start performing these composers was a tricky ask with a lot of financial risks attached, whereas convincing students, for example, to use free sheet music and consider taking up a short piece or two for a recital seemed like quite a reasonable aspiration. We basically broke the problem down in to the each separate hurdle: the lack of awareness, the lack of recordings for reference, the lack of high quality sheet music, the price of often sub-par editions for the music – and then we built Flip the Stem up to tackle each one: shout about the composers, get their best works recorded, renovate all of the crappy pre-1950 sheet music, and make it all freely accessible.

DS: Have you had any particular successes so far in bringing any composers or their music to greater prominence?

NJ: We’re very much a fledgling organisation, so we’ve not had such a noticeable impact yet. We’ve got a lot of content planned, but naturally we’re trying to show that we can be diverse in our selections, and I think inevitably it’s going to take more than a few pieces for each composer to popularise them. There are definitely quite a few that we have high long-term expectations for like Hedwige Chrétien and Maude Valérie White. The philosophy behind our core aim of diversifying common repertoire has always been that shorter, accessible pieces for small forces are easier to share and popularise, and from this perspective I think we can extrapolate that we’re probably going to find our footing primarily within contexts like student recitals earlier on. We know from experience that a lot of students are interested in diversifying their repertoire, but oftentimes it’s not easy to find composers or pieces to aid them in this, and they’re also one of the groups that are least likely to be able to take a financial risk on untested repertoire. Some of our commissioned performers have already told us how they wish they’d discovered their pieces before they graduated, as they would have been a perfect fit for their student recitals, so I’m confident that in time we’re going to have the intended impact.

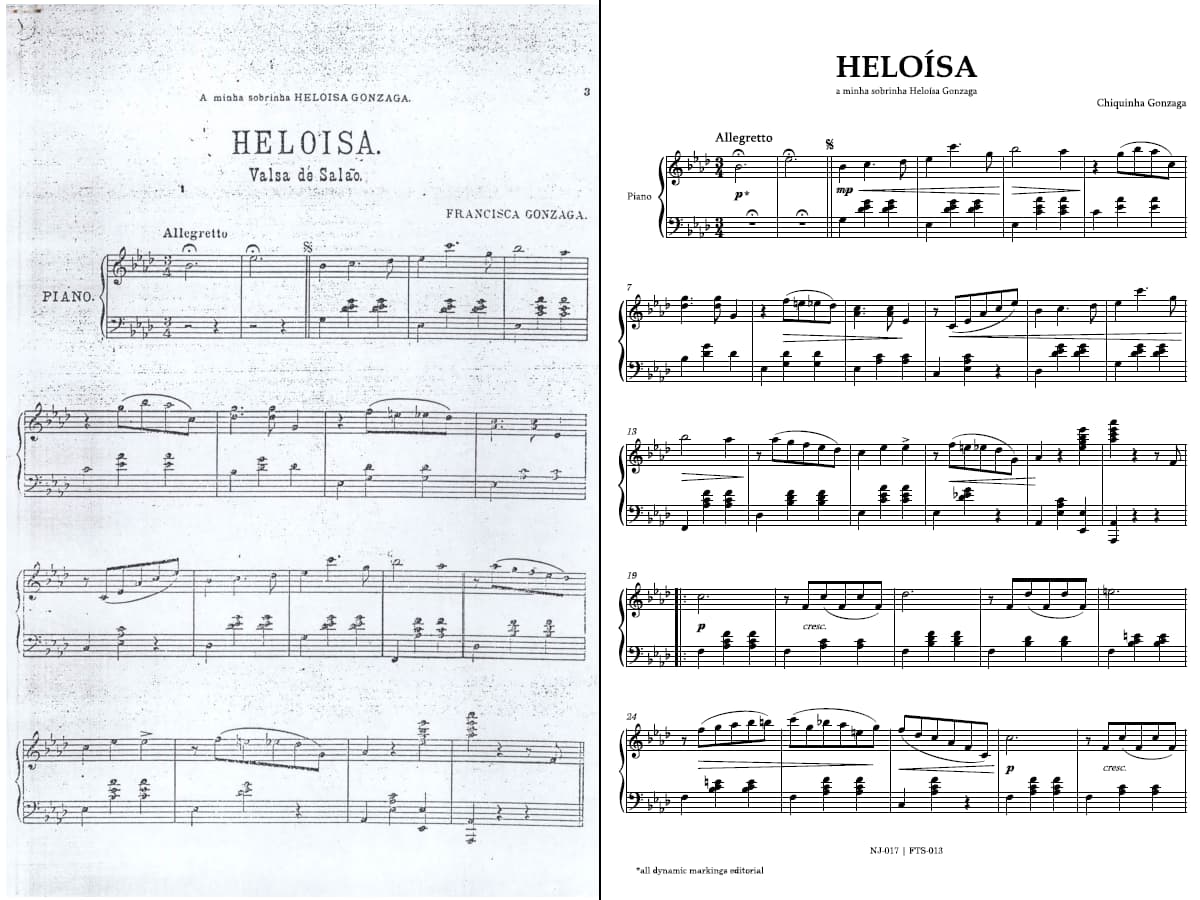

On the left, the original edition of “Heloísa” by Gonzaga; on the right, Flip The Stem’s new edition

DS: How do you identify the composers you’re targeting? Are there any particular historical periods, countries of origin, targeted forces, or perhaps gender (i.e. women!) that you are looking to promote?

NJ: Generally, we’re looking at female composers and composers of colour, but really the aim is to diversify the canon, so it’s less about what the composers are and more about what they’re not. We love the Western Classical canon’s greats as much as anyone else – we just think the classical music community is passing up on a lot of fantastic music by not taking the time to look outside of that ultimately rather small selection. For both practical and ideological reasons, we’re currently limiting ourselves to public domain – there’s a lot of odd misconceptions in music history about why the Western Classical canon is as white and male as it is, and I hope that our work will make people realise that chance, politics and social circumstance played a much larger part in defining the canon than most care to admit. As I mentioned already, we’re primarily looking at smaller forces – we’d love to look at some slightly larger chamber works, but that’s undoubtedly going to have to wait until the pandemic has passed.

DS: Your videos look great thanks to your expert use of Dorico and sound great thanks to the new recordings you’re making: how long does a typical project take from start to finish?

NJ: For just the copy work, a typical solo piano miniature takes no longer than a day. We go back to things afterwards to do extra proof-reads, etc, but it’s a pretty quick process otherwise. It can definitely vary depending on how much editorial work needs to be done, and if we start looking at the overall content production and factor in recording equipment delivery, video editing, and so on then that inflates things a bit more. I think the longest I’ve ever spent on a score has been three days, and that’s been for vertically and horizontally larger pieces. I don’t have a MIDI keyboard either, so my work pace is probably slower than it otherwise could be. Dorico streamlines a lot of the fine-tuning, which goes a long way in productively permitting my perfectionist tendencies. We started our initial planning back in July and officially launched in early December. There was a lot of groundwork that we won’t have to cover again, but all of that preparation should lead to us to releasing around 20 videos – about 2 hours of music – by the end of March 2021.

DS: Thanks for taking the time to talk with me, Nadim!

If you’d like to follow Nadim and Jenny’s work, check out the Flip the Stem YouTube channel. You can find the editions prepared for the videos on the channel on IMSLP here. If you’d like to get in touch with the team, you can make contact with them via Facebook, Instagram or Twitter.

I think I my have sent you a message meant for some one else. If so please accept my apologies. I though I was writing to the BBC, but if so then their contact page looks suspiciously like yours.

I just went to the facebook + other 2 pages but could find no way to contact them so I guess I wrote to you. (I don’t have accounts w facebook or the others, maybe that’s why). If you have an email or website for them would you send it to me please?

Many thanks

jw