Australian pianist-composer Wade Gregory recently won the 2018 Matt Withers Australian Composition Competition with his work Water Music, which he composed with Dorico. The work will be performed by guitarist Matt Withers and the Acacia String Quartet in a sold-out concert this Saturday night, as part of a series going on throughout August and September. I recently had the chance to interview Wade about his background, how he switched to Dorico from Sibelius while in the middle of a huge musical theatre project, and how Dorico helps him work more quickly.

DS: You were a first study jazz pianist when you were at university. How did your experiences as a performer inform your work as a composer?

WG: Most of my composing has been in the arenas of jazz and world music. I’ve written quite a lot for 18-piece jazz orchestra, and smaller 10-piece jazz ensembles. Often these pieces would be performed with only one or two rehearsals – I once had an arrangement premiered where the first read through was the performance itself! So I quickly realised the importance of clear, well laid-out charts. I also remember seeing a jazz gig where an esteemed composer came to town, brought his new compositions, and I watched as the poor bass player struggled to handle these poorly laid-out 12-page charts that were sticky-taped together: she actually had to stop playing completely at one point in order to adjust her music and stop it falling off the music stand. Thus a passion for clear, easy-to-read charts was born.

DS: Like many composers in Australia, you started out with Sibelius, and I guess you were using it for many years before Dorico came along. When did you get started with Sibelius?

WG: I have been a Sibelius user ever since version 2 in the early 2000s. I was first introduced to it at my high school in Brisbane and used it for all my music assignments. I then studied jazz piano at the Queensland Conservatorium Griffith University, and followed the software upgrades throughout my time studying. I was in a Brazilian band for several years, and wrote out all of the band’s charts using Sibelius. Over the years my friends all saw me as a sort of power user, and I would frequently get questions about how to lay out charts, tweak the default settings, create house styles etc. I’ve got no idea how many Sibelius files I have on various hard drives, but it would be well over a thousand.

DS: So you were with Sibelius throughout practically its whole evolution.

WG: I distinctly remember producing my first jazz orchestra score in the days before Dynamic Parts, and spent so much time extracting, editing and cleaning up parts. My jaw dropped when I saw Dynamic Parts in action, as I did later when Magnetic Layout was introduced. Similar jaw-drops have been made more recently when seeing Dorico’s handling of multi-movement works, cue handling, and lyric placement.

DS: What was it that prompted you to give Dorico a try?

WG: Strangely enough, I was in the middle of a large project. For the past two-plus years I’ve been composing, orchestrating and collaborating with others in my first original musical theatre project, Dookie: The Musical. Dookie is a small town near Shepparton, population about 300. I moved to Shepparton over four years ago, a laid-back but vibrant town of about 50,000 people about two hours north of Melbourne.

Since moving here I’ve started composing and arranging for choirs, theatre groups, orchestras, and other chamber ensembles, and the musical was a collaboration between the local theatre group and community orchestra, and featured multiple songs, reprises and incidental music, a variety of instruments and singers, and at one point there was a full 30-piece orchestra on stage performing live. I was becoming frustrated with the limitations of Sibelius when dealing with such a large-scale work, trying to use sub-folders and multiple files: I was losing track of where I was up to. I bit the bullet, spent a few weeks importing what I had at that stage into Dorico, and never looked back.

DS: We always hoped that composers would find the project management features of Dorico useful for complex and large-scale works with lots of moving parts, like musicals. How big did Dookie: The Musical get?

WG: In the end, Dookie: The Musical had about 30 flows, eight players in the pit orchestra, and a further 12 players in the stage orchestra. I produced parts for all instrumentalists, and several custom scores including a vocal score, a piano-vocal score, and a rehearsal score that contained only the flows for the on-stage “Dookie Symphony Orchestra” and those associated players. This was all contained within a single Dorico file. Using Dorico saved me multiple potential headaches: when the director asked for fewer bars at the end of one piece, I simply cut those bars across multiple layouts and custom scores and re-orchestrated them with no fuss. Similarly, we needed a new piece of incidental music late in the rehearsal process for only three players, inserted with no dramas thanks to Dorico.

DS: You’ve been able to make good use of the features to create multiple layouts combining musical material in different ways, then.

WG: Yes. In preparation for a rehearsal with the pit band’s string quartet I needed a custom score of a selection of flows with the vocal lines added in. In the time it took to enjoy a cup of tea I’d produced a layout containing six players and about 20 flows and exported it to PDF for my tablet. I created clear layouts for the pit band, featuring just the flows in which they were performing. In particular, the bass player’s layout was well over 60 pages and contained 25 flows. Most importantly, as musical-director I was confident that when it came to performances he would never have a tricky page turn or a confusing chart. The power and flexibility that comes from the architecture of players, flows and layouts is one of Dorico’s biggest strengths, I believe.

DS: Congratulations are in order for your win with Water Music. Tell me about how you came to write it.

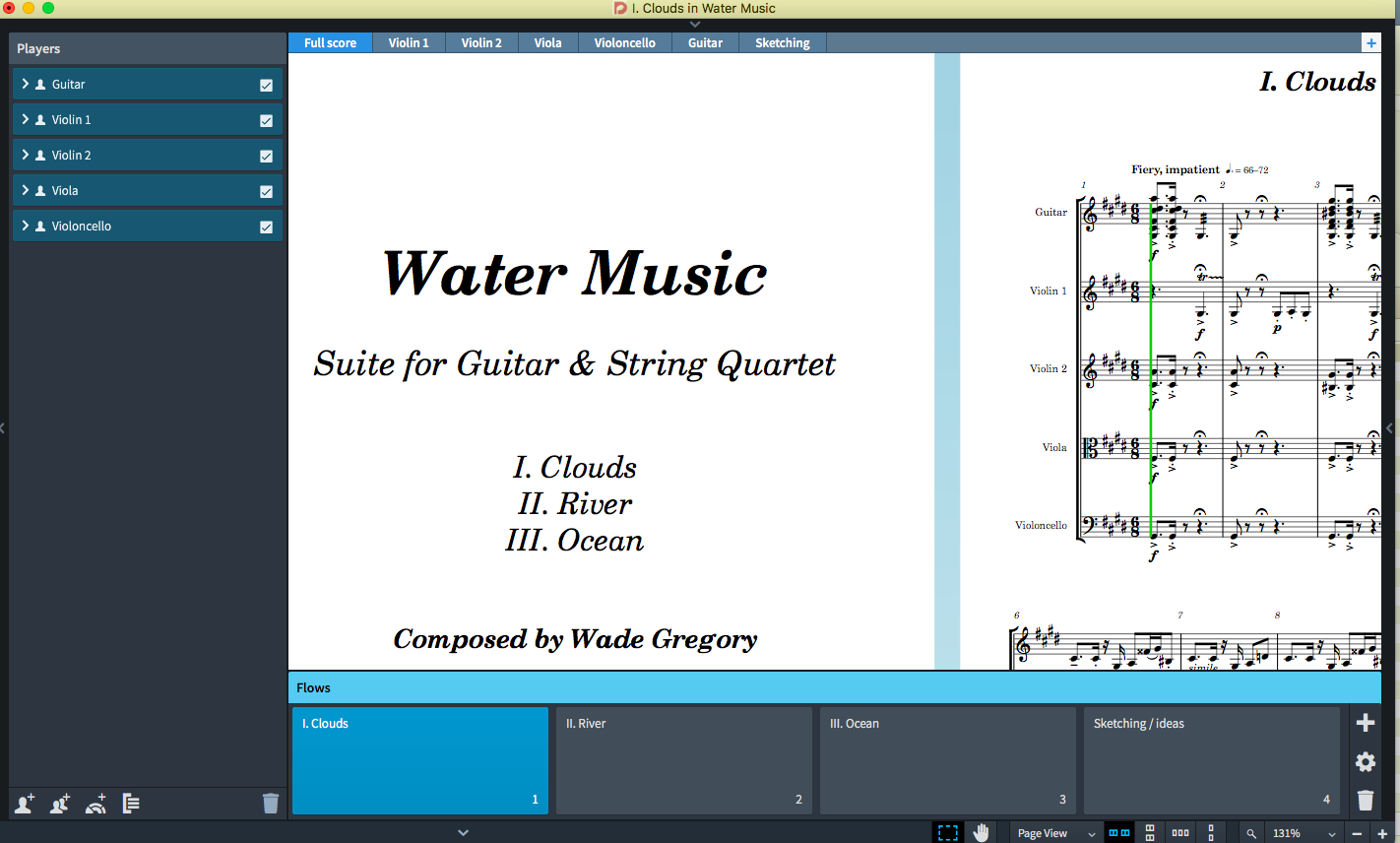

WG: It was during the middle of rehearsals for Dookie: The Musical that I heard about the Matt Withers Composition Competition on an orchestration Facebook group. I had recently finished the string quartet orchestrations for Dookie, all rehearsals were going well, Sitzprobe was still weeks away, and by some miracle I had a free weekend in my diary! I decided to enter the competition, which required a composition for classical guitar and string quartet of 8-10 minutes length in response to three artworks.

My entry for the competition, Water Music, has five players, three flows corresponding to the 3 movements (entitled “Clouds”, “River” and “Ocean”) and six layouts. The competition required printed score and parts, PDF files, and an MP3 mock-up, all of which Dorico handled with ease. The adjudication panel was Matt Withers himself on guitar, along with the Acacia String Quartet and composer Richard Charlton. I assumed that Matt and the quartet would be sight-reading multiple entries as part of the adjudication process, and so beautiful, clean parts were a must. My thinking was if they’re struggling to turn pages, decipher cluttered notation and read messy parts then they wouldn’t be concentrating on your music. And, given my time constraints of concurrently rehearsing Dookie: The Musical, speed and efficiency of note input and part layout were essential.

DS: Was Dorico able to support your compositional process in a new way, compared to Sibelius?

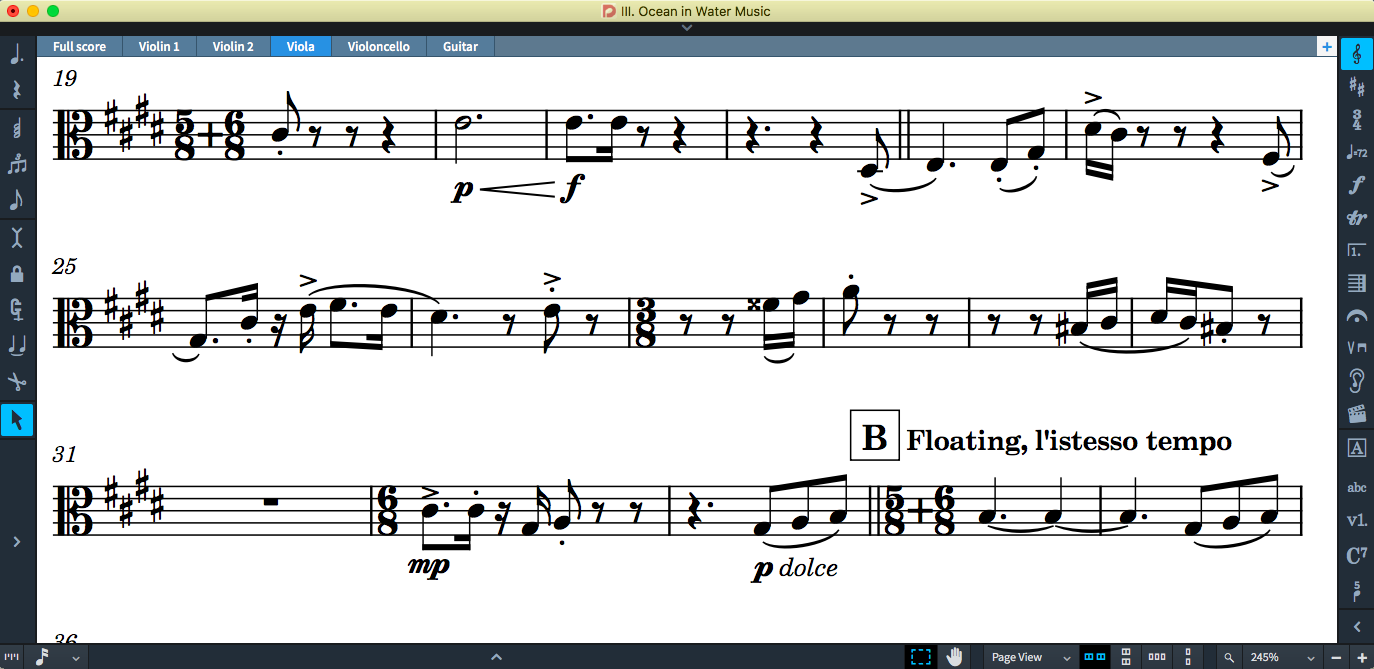

WG: The whole thing was composed directly into Dorico. I didn’t touch a piece of manuscript paper or pencil at all. I’d composed using alternating meters before, but when I was using Sibelius I found the workaround of putting in time signatures in every bar then hiding them to be quite laborious, even with copy and paste. I thought I’d put Dorico’s support of alternating meters to the test and wrote the first movement predominantly in 5/8+6/8. It was a joy! In some sections I went to 3/8 for several bars, and then eventually I found myself composing first and adding time signatures later: the use of the scoring program was being subservient to the compositional process, and not the other way around. Just the way it should be!

I used themes and melodies across the movements, developing and altering them slightly, and presented them in different instruments. Jumping between the flows was easy with a keyboard shortcut: no need to open another file, no need for an “ideas” hub. Again, multi-movement or multi-song projects are a breeze with Dorico.

DS: So you were able to actually compose at least part of the work directly into Dorico. As you say, the software has to be able to get out of your way for that to work.

WG: I particularly enjoy Dorico’s method of note entry. I often compose on my laptop at cafés, on the train, on the couch, wherever, and the system of keyboard shortcuts and popovers means I can quickly get ideas down and rarely have to use the trackpad. For Water Music, my guitar part is primarily two voices on a single stave, and Dorico’s method of handling multiple voices is easy and intuitive. I could easily compose into these two voices as the inspiration came, and not have to worry about creating voices, using the trackpad, deleting rests etc. Incidentally, a lot of my piano compositions and orchestrations feature multiple voices on each staff too, as do choral reductions, so I’m always utilising and appreciating Dorico’s support for note-entry into multiple-voices.

The clean, uncluttered workspace means that every inch of real estate on my laptop’s monitor is dedicated to the composing, and not focused on menus or toolbars.

One other small feature I’ve come to love in Dorico has been when writing vocal lines, either for choral compositions or for Dookie: The Musical. It’s very subtle, but the way that notes and lyrics “nudge each other” slightly to create enough room means you can easily produce beautiful, clear melody lines with well-spaced readable lyrics. I was forever tweaking lyric placement in Sibelius to get vocal lines to look just right – this now happens by default in Dorico.

DS: You told me that you recently updated to Dorico Pro 2 – what was it that prompted you to buy the update?

WG: I have to put out a cheer for NotePerformer. I’m a huge fan, and when I saw that Dorico 2 is starting to support NotePerformer I knew I had to upgrade. I’ve just in the last few days started work on a short film score and have been testing out Dorico 2’s support for video. And now that most things on my wish-list have been developed since I first switched over to Dorico – chord symbols, jazz font, slash notation – I’ve well and truly become a Dorico fanboy.

DS: Thanks, Wade!

If you would like more information about Wade, you can find him on Twitter @WadeGregory, and you can read more about Water Music and find out details of this weekend’s concert at Matt Withers’s web site.

If you’ve not yet given Dorico a try, there’s never been a better time. A free, fully-functional 30-day trial version is available and if you, like Wade, have a lot of Sibelius files built up over the years, try importing one or two of them into Dorico via MusicXML. You will be amazed at the quality of the import!