Bringing a new musical to the stage is an enormous task, especially in London’s West End, and many more musicals fall at one of the many hurdles that lie between the germ of an idea and a real production than make it all the way through the gauntlet. One new show that is coming to the stage later this summer for an initial limited run at the Theatre Royal Haymarket is a brand new adaptation of Kahlil Gibran’s Broken Wings, created by actor and writer Nadim Naaman and composer Dana Al Fardan with orchestrations by Joe Davison.

In an interview with What’s On Stage, Naaman said: “Gibran is the Shakespeare of the Middle East, and the third best-selling poet of all time. His views transcend nationality, politics and background, read by all faiths and all ages. He was spiritual, but wouldn’t dedicate his life to one particular organisation of religion. Instead, he took the best of all faiths, championing humanity, tolerance and love above all else. I still can’t believe that the book hasn’t already been adapted for the stage; it is structured like a play, and is awash with musical references.”

The cover of the Broken Wings concept album

The tale of Broken Wings is one of tragic love, set in turn-of-the-century Beirut. A young woman, Selma Karamy, is betrothed to a prominent religious man’s nephew. The protagonist falls in love with this woman. They begin to meet in secret: but they are discovered, and Selma is forbidden to leave her house, breaking their hopes and hearts.

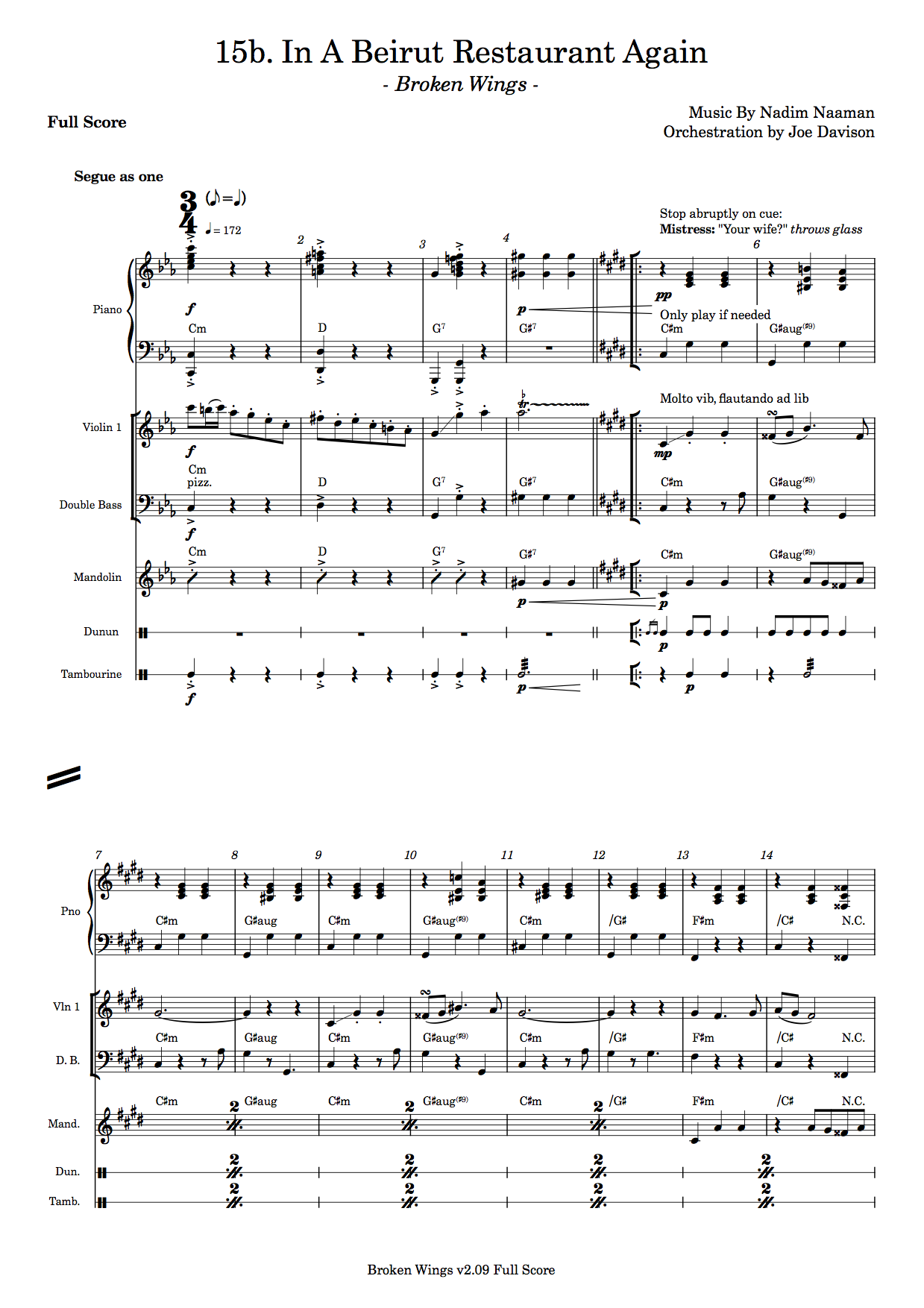

The show’s orchestrator Joe Davison has prepared all of the performing materials for the show using Dorico. I caught up with him to find out more about his work on the show and its journey to the stage.

DS: Thanks for taking the time to talk about the show with me, Joe. How did you get involved in this project?

JD: I’ve been working with composers Nadim Naaman and Dana Al Fardan on this show for the best part of two years now, originally in order to make the concept album which I produced, and gradually growing to the stage we’re at now, with a week long run at the Theatre Royal Haymarket. We agreed very early on that although the story is set in Lebanon, the narration is coming from New York, and that the music is being born out of this older version of Gibran’s telling of the story. So we settled on a sound world that is largely western, with an orchestra comprising a string quartet, double bass, piano, guitar and mandolin, with the Arabic influences emerging through harmonic choices, stylised playing, copious percussion and the other-worldly sound of the hammered dulcimer, which I absolutely love. This duality derived from a dialogue and tension between east and west runs throughout the show both musically and thematically, as it did through Gibran’s life. As if by serendipity, Dorico was growing as I needed it alongside the orchestration: when I started the project I only needed to score out the string parts and vocals, which Dorico was already more than capable of handling and I thought it would be a fun experiment to switch over from Sibelius. Since then, percussion support arrived just when I needed it, followed by large time signatures ready for me to actually conduct the show, and the new ossias have been perfect for filling with cues and creating a rehearsal score with piano, vocals and cued band parts!

DS: Preparing the performing materials for a musical is enormously time-consuming and complicated, regardless of which tool you use. Is there anything about Dorico that has been especially helpful during the process?

JD: There are so many things I love about working in Dorico: as a mathematician I really appreciate the structure on which everything is built. The popover setup means things are where you’d expect them to be, objects behave like those objects should. One of the things that first attracted me to writing a musical in Dorico was the setup screen itself. The idea of each musical cue being a flow with specified players makes so much sense, and being able to easily re-order and duplicate flows, as well as copy motifs from one flow to another all within one file is exactly how I think about a show in my head. Another massive help is the implementation of cues. Being able to reference cues for players in a musical who often have large chunks of rests and know that even if we change something during the rehearsal process the cues will still make sense gives a real peace of mind. I’m also really pleased to have been able to create an effective (and dynamic) contents page for all the parts – all these little things add up to knowing that the rehearsal process is going to be so much easier.

DS: How would you like to see Dorico develop in the future to further support your work?

JD: Most of my work is producing records and I work primarily in Cubase: in fact, a large portion of Broken Wings started out in Cubase as I made demos of the orchestrations for the composers. I’m so excited about the future integration of Dorico and Cubase – at the moment I often work backwards, building things in Cubase and then scoring what needs to be performed by actual people, but the idea of reversing that process and starting back with the dots is the way I’d much rather work. Typing and thinking musically in Dorico is so easy, so I feel like this future isn’t far around the corner.

DS: Thanks, Joe. I wish you and the team huge success with the show when it opens!

If you would like to see Broken Wings for yourself, the producers of the show have provided an exclusive discount code that will allow you to save 25% off the normal price of tickets if you purchase through this link. Find out more about the show at its official web site or by following @BrokenWings2018 on Twitter. You can even download the original concept album from iTunes. You can also find Joe on Twitter @AuburnJamJoe.

If you’ve not yet tried Dorico for yourself, you can download a free, fully-functional 30-day trial version from the Steinberg web site.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks