Luke Corradine is an award winning film composer as well as the co-founder of Fizz-e-Motion, an international film distribution company. In addition to his successful career in film composition, Luke plays a pivotal role in managing the publishing and scoring department at Fizz-e-Motion. Recently commissioned by the founder of the Alborada Classica Music Festival in Granada, Luke composed a new piece for the Ukrainian film Bread (Shpykovskyi, 1930), which was premiered at the Festival on February 10th, marking Luke’s culmination of a trilogy of film scores composed for three Ukrainian silent films over the past two years. I had the pleasure to speak to Luke, who walked me through his composition process, his Dorico workflow, as well as his decision to adopt Dorico, switching from other notation software, highlighting the benefits it brought during the intense four-week composition period to meet his deadline. Keep reading to find out more about Luke’s creative process, the advantages of Dorico in film scoring, and his valuable advice for aspiring composers.

Premiere in the Alborada Clasica Music Festival. (L to R): Alfredo Garcia (famous Spanish Baritone); Duncan Gifford (Pianist of Teatro Real in Madrid); Kateryna Shevchenko (founder of UFACE and cultural manager); Luke Corradine; Alexis Soriano (orchestra conductor and director of the festival Alborada Clasica).

AN: Hi Luke, it’s great to talk to you! Can you share a bit about the film score commission for the Alborada Clasica Music festival in Granada? What inspired the project, and what are some key elements you’re incorporating into the composition?

LK: The founder of the festival had heard my score for the classic film Zemlya (Earth, 1930) by Oleksandr Dovzhenko which had been premiered in July 2023 at the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures in Los Angeles, so he contacted me to ask if I would accept to compose a new score for a second Ukrainian film of the same era: Bread (Shpykovskyi, 1930) to be premiered at the Alborada Clasica Music Festival. For the task I was introduced to famed Australian pianist Duncan Gifford from Teatro Real in Madrid, who happily accepted to perform my score at the premiere. Duncan is a highly regarded international pianist. With his involvement, I decided to bring new and more advanced elements to the score and introducing a more advanced pianistic idiom, as well as a rigorous thematic architecture which supports the multi-layered narrative of the film. This score closes for me a trilogy of Ukrainian silent films I have scored in the last two years, bringing Ukraine’s great cinema legacy to the forefront internationally and opening this type of cinema to a new generation of fans.

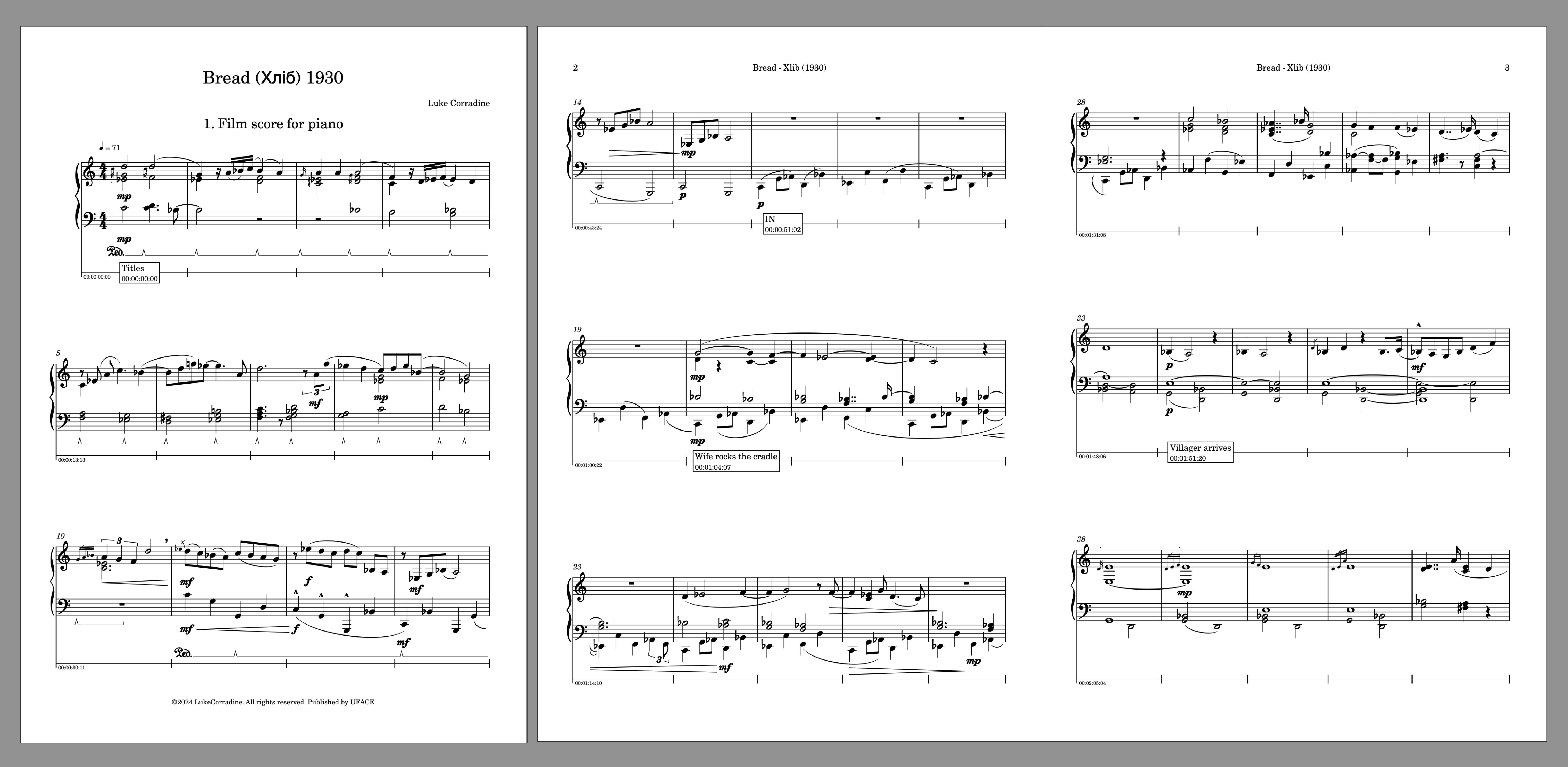

Bread, composed by Luke Corradine in Dorico

AN: I understand that this is the first time you used Dorico exclusively for the first stages of the work, without using a DAW software at all for your composition process. What prompted this decision, and how has Dorico’s new capabilities enhanced your creative process?

LK: I had grown very uncomfortable in recent years with the notation side of my previous DAW (Pro Tools/Sibelius) and was also keen to get out of its subscription payment model which made me feel constrained. In July 2022 the Spanish Filmoteque (Filmoteca Española) commissioned a film score from me to be premiered at their famous Cine Doré in Madrid. Early that year I was convinced by my colleague Nikita Budash (Kazka) to try Cubase which I was loving and so, based on my positive Cubase experience, I chose Dorico as my new notation software. It was a leap of faith as I had little time to write the full 58 minute score – just four weeks, travelling between Kyiv and Madrid, working on late night busses, night trains and under several air raid alarms. It was an intense but beautiful experience and Dorico proved a solid, and easy to use, working platform. The first thing I noticed is the elegance and stability of Dorico’s engine alongside a popover ecosystem which was intuitive, comprehensive, and a joy to use.

Based on my positive Cubase experience, I chose Dorico as my new notation software. It was a leap of faith as I had little time to write the full 58 minute score in four weeks, travelling between Kyiv and Madrid, working on late night busses, night trains and under several air raid alarms. It was an intense but beautiful experience and Dorico proved a solid, and easy to use, working platform. The first thing I noticed, is the elegance and stability of Dorico’s engine alongside a popover ecosystem which was intuitive, comprehensive, and a joy to use.

Silent Sundays Presents a Screening of Earth (Zemlya) with Live Musical Accompaniment, Featuring Luke Corradine: Composer and conductor; Aron Kallay: Piano; Laila Zakzook: Viola; Kayvon Sesar: Violin; April Dawn Guthrie: Cello; Alex Russell: Violin; Kateryna Shevchenko: Synth Harp and Celesta; and Abe Gumroyan: Bass, on Sunday July 23, 2023 at The Academy Museum of Motion Pictures, Los Angeles, California

AN: Could you walk us through a typical workflow when using Dorico for film scoring? Are there specific features or tools within Dorico that stand out in this context?

LK: When I first started using Cubase and Dorico in 2022, I used to improvise my work at the keyboard in Cubase and then I used Dorico to polish the notation side. In this early-days set up of mine, Cubase would be used to produce the audio score side, and Dorico the notation side. But I soon realised that Dorico would allow me – via its marvellous Play Mode – to retain all the human feeling and details from my playing. This was a game-changer and it meant that, for the first time for me, a notation software could be used to actually present mock-ups of the highest quality without turning to a DAW. Working exclusively for film with Dorico allows me to compose and finalise up three to four minutes of fully notated and beautifully sounding score a day, while delivering to clients, collaborators and musicians, not only notation, but also all other necessary deliverables, in record time.

I soon realised that Dorico would allow me – via its marvellous Play Mode – to retain all the human feeling and details from my playing. This was a game changer and it meant that, for the first time for me, a notation software could be used to actually present mock-ups of the highest quality without turning to a DAW. Working exclusively for film with Dorico allows me to compose and finalise up three to four minutes of fully notated and beautifully sounding score a day, while delivering to clients, collaborators and musicians, not only notation, but also all other necessary deliverables, in record time.

AN: What advantages have you found in utilising Dorico over other software, especially in the context of film scoring? How has it impacted the efficiency and quality of your work?

LK: I started composing to picture in 2008 with Pro Tools but as my work become more sophisticated and involving bigger productions, I simply couldn’t make the old software do what I needed. When I scored the film No Panic With a Hint of Hysteria featuring Stephen Baldwin, I was in London and all my musicians recorded remotely in Los Angeles. Transferring MIDI across to my conductor for the recording sessions proved very time consuming. I realised I needed a much more reliable notation system. When I arrived at Dorico in 2022 I felt I had been living in the clouds. I cannot stress enough the importance of Play mode, the potential of which is enormous for the future, especially with Steinberg’s expertise in DAW. Having a reliable and fully customisable audio workspace, inside the notation software, allows for a complete new sonic experience for any composer committed to traditional notation. Another aspect of Dorico that is extremely powerful is flows. I, for example, always keep ‘Flow 1’ for my main score work. After that, I have ‘Flow 2’ which I can access with one simple customised key stroke. Flow 2 is dedicated to sketches and ideas, where I freely improvise and create themes and materials that might or might not be used in Flow 1. After that I keep any number of flows I may need, for presenting scenes or single themes to clients. These flows are also references for the future, where I can easily keep track of previous theme versions, for example.

Luke Corradine conducting at Spanish premiere of Zemlya

AN: Can you share any challenges you encountered throughout this project and how Dorico played a role in overcoming them?

LK: Half way through this project I fell really ill with the flu. Two weeks went by in bed putting my deadline at risk. When I recovered I understood I had to rely on Dorico to improve the time I spent to execute all repetitive functions, of which there are always many in notation work. I created a whole new set of very intuitive keystrokes affecting everything from changing a voice, deleting rests, adding rehearsal marks, changing tempo, adding time code markers, turning notes into acciaccature/appoggiature and viceversa, adding harmonics, etc. I wrote all these on a board which I kept in front of me all the time and within a day I was working much faster, typing on the computer keyboard any manner of key commands for editing and polishing the score, at an unparalleled speed for me. In ten days the score was done and delivered to the festival organisers and pianist.

AN: For composers considering a shift to Dorico music notation software for film scoring, what advice would you give based on your experience with this project?

LK: As you probably realised, I am a big fun of the Play Mode. For us who have spent years with DAWs and are used to finesse audio to perfection, the addition of Play Mode allows for a much higher level of expressiveness. For example: recently I was changing the feel of some arpeggios in Play Mode. I wanted the first two chords to sound rather tight while the second pair much wider sounding and with notes further apart. It took me two minutes to customise the feel I needed and after that I added some text comments for the players. The result was fantastic and allowed me to show the film’s producers and collaborators, exactly what sound I intended. This summer we are organising a series of masterclasses in Madrid through my non-profit organisation UFACE, for young film composers and I would like to bring Dorico into focus, teaching aspiring film composers to feel confident about using notation software from the inception to be able to create high quality mock-ups in the box.

AN: Thank you very much Luke!