Michele Galvagno is a professional Music Engraver and a graduated cello/music theory teacher with over twelve years of experience, creating the beautiful scores behind the Artistic Score Engraving label. Among his recent endeavours is the Piatti Opera Omnia – a remarkable project dedicated to unveiling the unpublished musical compositions of Carlo Alfredo Piatti (1822-1901), a prominent cellist and music composer mostly famous for his Twelve Caprices. Beyond these renowned Caprices, Piatti’s solo cello repertoire includes the captivating Capriccio sopra un tema della Niobe di Pacini, Op. 22, a musical piece about which not much is known. In a conversation with me, Michele Galvagno delved into the intricacies of this project, sharing insights into the challenges he faced, and detailing his experience transitioning from Sibelius to Dorico music notation software.

AN: Hi Michele, what can you tell me about the Piatti Opera Omnia project and its significance? What inspired you to undertake this project?

MG: Carlo Alfredo Piatti (1822–1901) was one of the greatest cellists of all time, and yet he is known only for his Twelve Caprices, Op. 25, for cello solo. He was from Bergamo, Italy, even though he spent most of his professional life in London. I visited Bergamo and the library where all the scores once owned by Piatti are kept many times in the past fifteen years—small curiosity: they are still in the same cupboard and in the same classification where he left them. During one of my visits, I stumbled upon a few unpublished manuscripts by Piatti that attracted my attention: a piano accompaniment for one of the Twelve Caprices, and a quartet for four cellos dedicated to the students of the Istituto Musicale in Bergamo.

Those two were among the very first editions I published with my label—Artistic Score Engraving—back in 2018. Since then, I have set a goal to create modern editions of everything Piatti wrote, starting from the unpublished works that never made it past the manuscript stage. There are over 100 pieces, and I am just getting started. I believe Piatti’s production outside the Caprices is unjustly ignored, and deserves more attention.

AN: What led you to choose Carlo Alfredo Piatti’s piece from the opera Niobe by Pacini for your project? What makes this piece unique?

MG: Piatti wrote this Capriccio sopra la Niobe di Pacini around 1843, when he was still trying to get a concert career in mainland Europe. It is known that he performed it in Budapest, before falling gravely ill and having to even sell his cello to get back to Bergamo. The piece then got lost and would have not been published until 1865 when Ricordi released it, sadly plagued with mistakes. This edition aims to correct all those glaring errors and give performers and students a reliable source to enjoy.

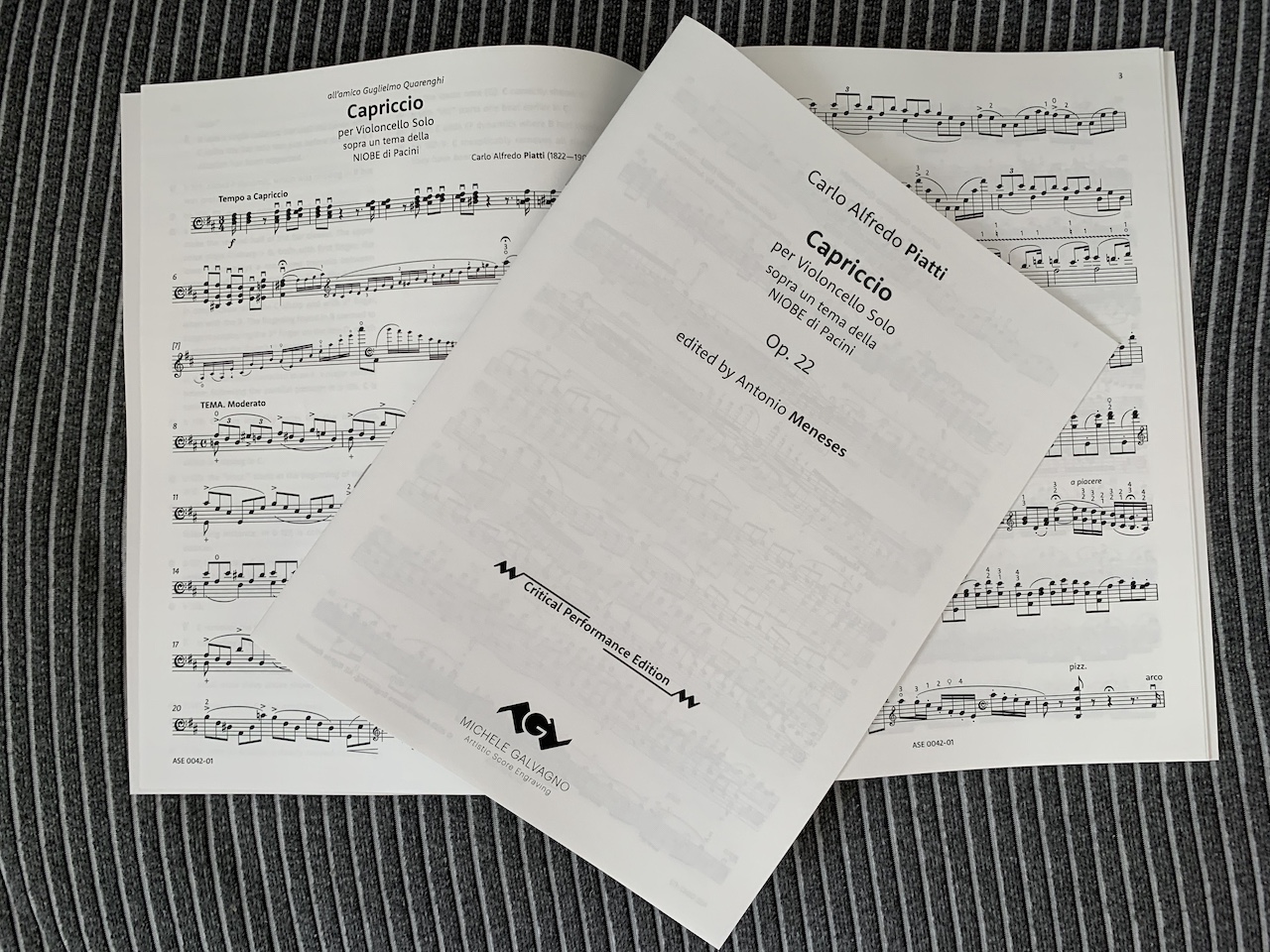

Several aspects make this edition unique: firstly, a thorough musicological research welcomes the reader with an Agatha Christie-like investigation on the opera Niobe itself, whose themes were used by several composers in their variation sets (one among them: Franz Liszt), with the opera itself, though, disappearing from all radars. Second, this is the only other piece for cello solo composed by Piatti. At the time, “solo cello” was not a popular instrumentation, and concerts with only one cello on stage were just not a thing. This makes every previously lost piece for solo cello from the XIX century a true gem. Finally, I had the immense honour of involving Master cellist Antonio Meneses into the project. He recorded this piece on his CD “Capriccioso”, and he gladly accepted to contribute to this edition. Beside the main booklet containing the Editorial Notes, the Score, and the Critical Notes comparing all sources, there is also an insert with a copy of the Score including fingering and bowing suggestions by M° Meneses. Here’s a picture of the printed edition:

AN: As I understand this was the first project you realised in Dorico. How did you approach the challenge of switching from Sibelius? What were the key differences or advantages you found in Dorico for this particular project?

MG: In truth, this was not my first edition in Dorico, but was the one that finally demonstrated to me that Dorico was ready for being adopted as a top-level tool in the sheet music publishing industry. The Piatti Opera Omnia, started in 2018 but accelerating from 2022—Piatti’s 200th birthday—, was actually my challenge to finally bring my Dorico level to the same I had with Sibelius. For all of 2022, I challenged myself so that every edition of a piece by Piatti would have had to be realised in Dorico, without compromises. The scores had to look as beautiful as they did in Sibelius and, upon taking two editions made each in the other software, a reader should have not been able to recognise which software created one or the other.

Switching from Sibelius required the creation of a different mindset, since the two software take very different approaches to almost every aspect of the score creation process. When I didn’t know how to do something, the first instinct was to ask myself “How would I do this in Sibelius?”, and try to find how that same thing was realised in Dorico. That soon proved to be a misleading path, though. To avoid confusion between the two software that, as a professional, I use every day for different projects, I had to consider them as two completely separated entities.

The excellent online Dorico documentation proved crucial in this process, and so was the public forum, incredibly active and full of generous people who never hesitated to lend a helping hand.

The key differences that made this project a joy to realise were, among others, the Note Spacing tool in Engrave Mode and the level of precision achievable for Slurs and Ties in Engraving Options. I am very picky about the design of slurs and ties, and about beam angles, maybe even too much, but Dorico gave me so many options that, ultimately, I could achieve exactly the design I was looking for. The main thing I noticed when working on this score was that, compared to Sibelius, I had a lot less to fix graphically when looking at slurs, ties, stems, and beams, which eventually resulted in more time available to dedicate to the artistic process.

Dorico’s note spacing engine is just unbelievable. I’ve been using notation software for the best part of the last twenty years, and I have never found anything that could even compare to what Dorico can do in this respect.

AN: Were there any features in Dorico that helped you save time for your part preparation and engraving process?

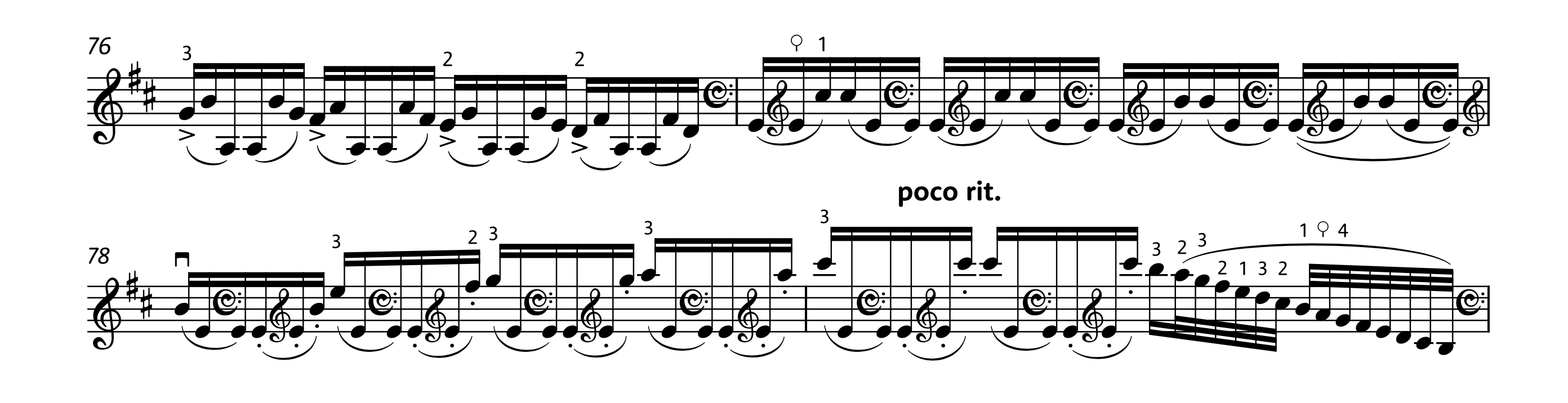

Please look at the following excerpt from this edition:

One of the challenges of writing for cello is that we use three clefs (bass, tenor, and treble). This causes uncomfortable issues with note spacing.

Both Finale and Sibelius have “tricks” to work around this, but what you see above is all native Dorico!

To be honest, these two lines are probably the only ones that Sibelius would have not allowed me to realise—at least, not to this level. Granted: the default output from Dorico is not like this, but we are given the possibility, with the Note Spacing tool in Engrave Mode, to get to this result in a very reasonable amount of time. Another plus: once set, it doesn’t move!

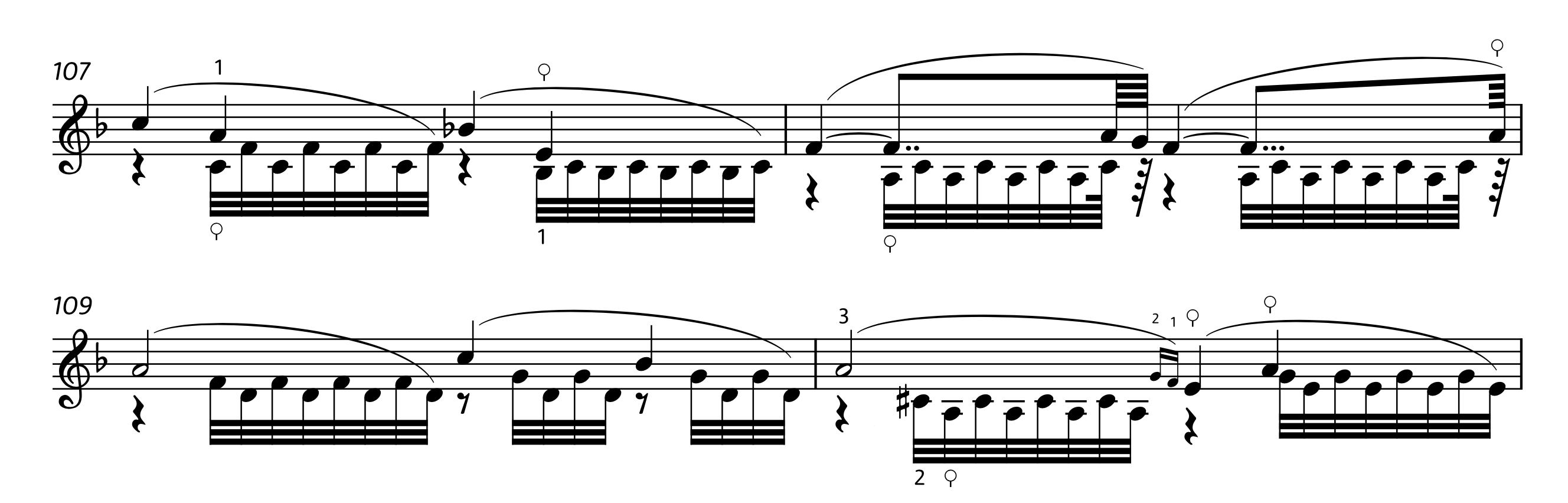

Another example delves into multi-voice passages:

Look at how regular the note spacing is! Even when we have double- or triple-dots in the upper voice, the lower voice is spaced independently!

This was a game changer for me! Then, fingering placement is excellent, with minimal adjustment needed from the user. Furthermore, those smaller digits for the grace notes are made small by default, no extra action required.

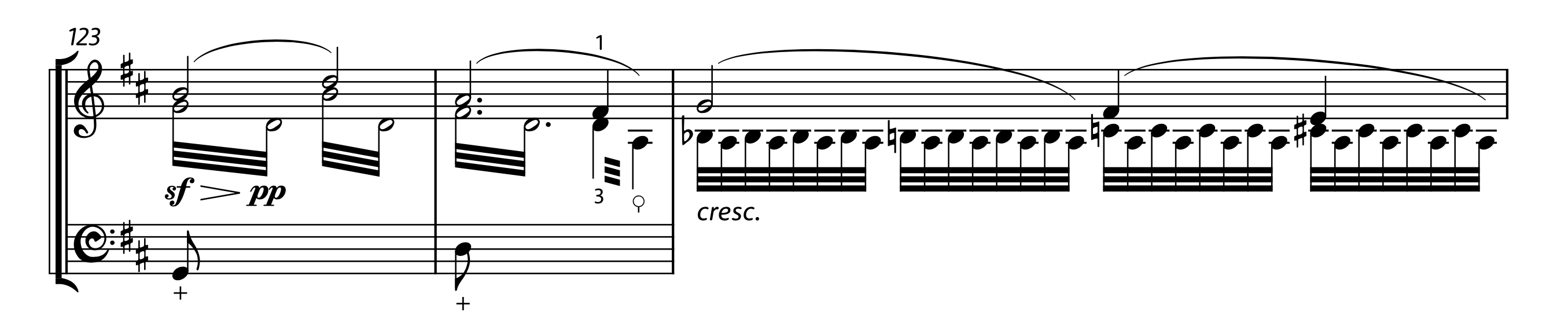

Finally, an example of using Extra Staves in Dorico:

To achieve this in Dorico, one simply needs to right-click on the top stave and choose “Add Staff Below”. That’s it! No fiddling in panels, instrument changes, etc… it is all there!

These are just three examples of a score with more than 250 bars. Add all these things together, and it comes to a considerable amount of time saved that can be dedicated to artistic choices.

AN: How was your overall experience using Dorico, and what advice would you give to others considering a similar switch in music notation software?

MG: All considered, I was impressed by the stability of the software. I am a Mac user and, while general operations require more time in Dorico than in Sibelius on my machine—a 2016 MacBook Pro looking forward to a well-earned retirement—, version 4.x, with the app now being Universal Binary, started to turn the tide. Even on my system, I was surprised at how Dorico’s performance improved over the last few years.

To users considering switching, or at least giving Dorico a try, I suggest starting small, with a solo or duo project. If you want to be blown away by what Dorico does like no one else can, try a vocal, guitar, or piano piece. The way Dorico handles lyrics is astounding, something that leaves me open-mouthed every time. The note spacing for cross-staff notation in piano music is incredible, and within-staff guitar fingerings are a blessing! Once you are comfortable with these, you can venture into bigger and more complex scores and enjoy everything Dorico has to offer.

AN: What’s next for your “Piatti Opera Omnia” project, and are there any upcoming projects or collaborations in the pipeline?

MG: The next steps in the “Piatti Opera Omnia” project will walk the path of cello and piano music, alongside something special involving the voice. Stay tuned about that! I have recently started a deeper collaboration with the city of Bergamo, publishing the Concerto for cembalo [fortepiano] and orchestra by Johann Simon Mayr—Donizetti’s teacher if you didn’t know him. This, from full score to parts to piano reduction, was all realised in Dorico, taking full advantage of the layout and instrumentation flexibility offered by the software.

AN: Sounds great! Many thanks for your time Michele!