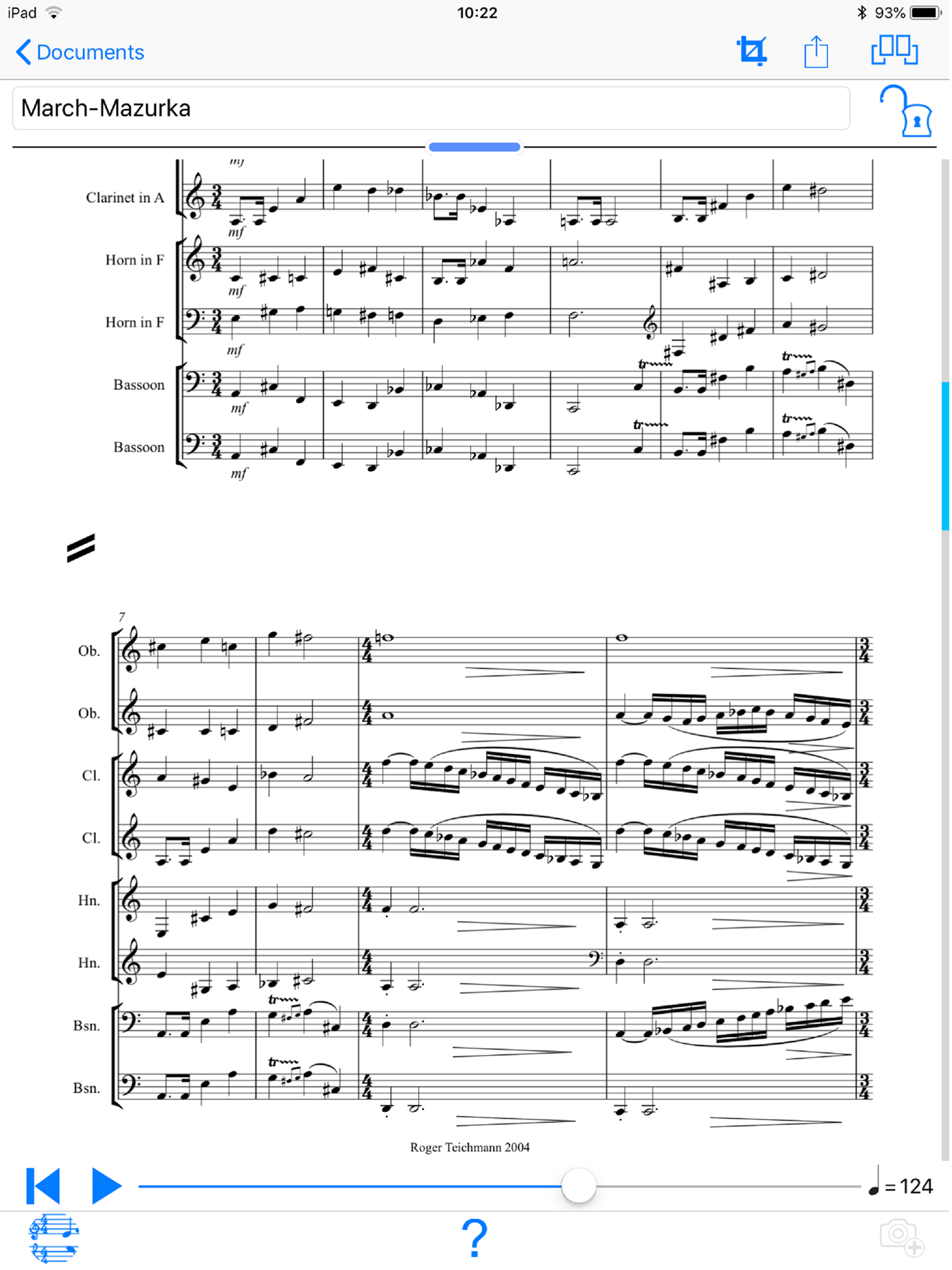

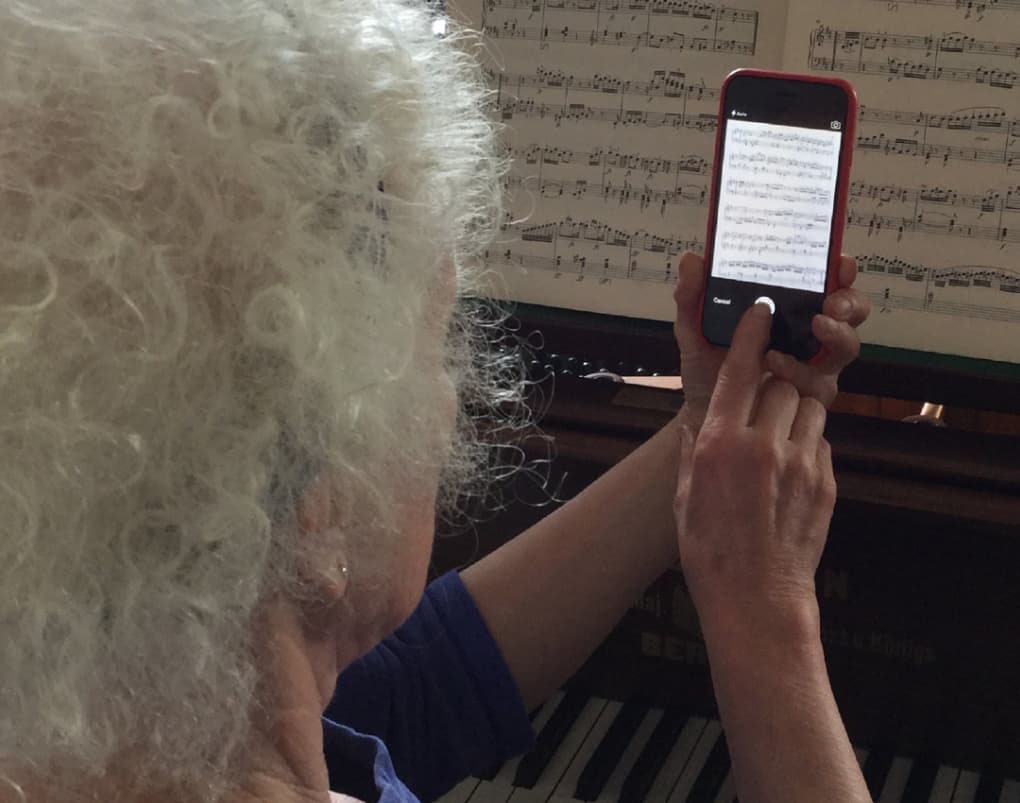

With the arrival of Dorico for iPad this past summer, it’s been exciting to dive in to the wider ecosystem of innovative apps for musicians available on the App Store. One of my own favourites is PlayScore, which is a sheet music scanning app that practically works like magic: simply point your smartphone or tablet camera at a page of music, take a photo, and just a couple of seconds later you can hear it played back. You can also send MIDI and, perhaps most usefully, MusicXML to other apps on your device, including Dorico. You can go from a printed page of music to that same music being edited in Dorico in a matter of a minute or so, which is hugely useful and can save a lot of time typing or playing music into Dorico.

As an example of the kind of novel workflow that a tool like PlayScore makes possible, here’s a video of tenor Charles Kim singing Wagner along to PlayScore’s playback of the aria he has loaded into the app:

Just like having a fully-featured music notation app like Dorico available on your iPad allows new kinds of creativity in new settings, being able to simply take a photo of a page of music and then be able to sing or play along with it just a few seconds later is something that musicians could only have dreamed of even a few short years ago. I sat down with the developer of PlayScore, Anthony Wilkes, to talk about how the app came to be, and how it will evolve in the future.

DS: What was the original impetus for working on PlayScore?

PlayScore creator Anthony Wilkes

AW: The original project was to develop an Software Development Kit (SDK) so that developers could build a music reading capability in their software. Optical Music Recognition (OMR) comes into many applications, beyond the obvious music scanning uses, and we wanted to build a fast accurate plug-in for general use in the music application industry.

That project was realised around 2015 and we now license an add-in called ReadScoreLib to other developers around the world. Some of the applications are a long way from what we mostly think of as music scanning, and might surprise you. We were involved in one project to control operatic lighting and potentially stage automation by synchronising with the orchestra through automatic score following. We have also licensed the SDK for use in more than one automated page turning application, and even a publishing company in China that use our system so that people can order music using a photo.

From a commercial point of view there are several reasons I felt an OMR start-up would be viable in principal. Firstly, the need to convert music notation into electronic formats is not going to go away. Even with formats like MusicXML and MEI, notated music in its visual form will always be the primary representation of music. Regardless of how music may be delivered in the future, notated music will always be the basic thing represented or encoded. This primacy of music notation means that the need to convert from it to other formats, whatever they are or will be in the future, will always exist.

Another good reason for working on OMR is that music as a language, although evolving, is doing so relatively slowly, and mostly at the edges. This means that time spent improving our OMR will go on being useful for a long time. As a software development opportunity, compare that with say a program for doing one’s income tax. There, what you develop one year is, as likely as not, out of date the next!

Coming to PlayScore specifically, the possibility of an app as we now know them did not exist then. However there was already much music on the internet, and the possibility of making it immediately audible, as one could already do with text very much interested me. And even at that early date, the need for handy OMR systems for the general musical public was becoming more and more obvious.

DS: You’ve been working on the technology behind PlayScore since 2006. Mobile phones with lots of computing power and high-quality cameras didn’t really exist back then – when did you first start to see mobile devices as the primary place people would use your technology?

AW: Looking through the source code I see the earliest comments are actually from late in 2005. However I cannot claim to have spent all that time working on it. For example I took a break for to write the handwritten music recogniser in Neuratron’s NotateMe. Now, however, it is my sole development interest.

As you might expect I saw the possibility of an OMR app pretty early on. As smartphones became more common I remember asking a few musical friends to send me photos of their music. What I got horrified me! A smartphone photo is not like a scan with clean, straight staff lines in crisp focus. In a photo there are no straight lines and everything is subject to a galaxy of optical distortions. All these distortions have to be undone or accommodated. In practice too, people will snap music in any state of preservation, and at any angle. Actually I was not the only person working on this problem at the time. I remember Martin Dawe from Neuratron telling me that they used to take a sheet of music and screw it up into a ball. Then they would open it out and give it a try!

But for me the dream that one could take a photo of a Beethoven piano sonata and hear it play immediately, with dynamics and articulation was highly compelling, and very motivating.

Another good reason to develop an app was as a demo for our OMR toolkit. For that purpose PlayScore 2 is very convenient. People looking for an OMR library to build into their software can do all the testing they like using PlayScore 2. This of course saves us a lot of work.

DS: You must get a lot of feedback from musicians who are using PlayScore in interesting ways. Have there been any particularly surprising stories?

AW: We get lots of feedback through our support and social channels, and we see a lot of scores – of all sorts. They range from nursery rhymes, through hymns, piano music, songs, sonatas, band and chamber music, right up to full orchestral scores. Musical theatre and opera is well represented, and we see some modern scores too.

We very much like to hear from users and we rely on the varied examples they send us to improve our OMR. Actually technical support is one of my favourite activities! I spend an increasing amount of time talking to fellow musicians and hearing about their musical projects. It is a special pleasure to hear from fellow cellists.

The range of projects is as varied as the types of music, some quite ambitious. One user is using PlayScore to extract the two hundred or so leitmotifs from Wagner’s Ring cycle. He is compiling them into a reference for use in studying the operas. And on the Wagner theme, on YouTube you can see Korean tenor Charles Kim singing extracts from Tristan und Isolde – accompanied by PlayScore 2!

Another interesting use is a project to compile a large body of MusicXML generated by PlayScore, for use in the statistical analysis of keys, themes and motifs. This is something I believe we will see more of in the future. There is now much academic musicological interest in OMR, not least because of the huge online score libraries in existence today. These libraries, together with OMR technology hold out the possibility of doing “big data” style research into the world’s music. Some have suggested that big musical data sets will enable computers to learn musical intelligence; and even to compose.

The fastest growing use of PlayScore is probably in education, mainly because of the wide range of uses. Dorico users will know PlayScore mainly for its ability to turn a PDF score into editable notation, but the app is not called PlayScore for nothing and if you are learning an instrument, having an accompaniment easily to hand can be very useful.

The app is also widely used to prepare rehearsal scores for choirs, both in and out of education. Here the choir director scans the score and sets up a part-separated playing-score for each voice. These can be distributed to the singers who can interact with the prepared score using the free PlayScore download. Because it is available on Android as well as iOS all the singers will be able to have the same practice experience.

DS: You’re always working on improving the speed and quality of the recognition engine in PlayScore. Can you say anything about what the future holds for the technology and the app?

We certainly are! We want to improve accuracy and coverage, as well as the features the app offers. For example the next release will include a metronome count-in facility, probably the single most requested new feature. This is not as easy as it sounds but it is now working in the lab.

Accuracy in the end is the most important, and the most difficult thing to improve. The problem is not by any means entirely the computer vision side of OMR. It is one thing to have the symbols and constructs correctly recognised. It is another to fit them together and render them in sound the way a human sight reader would do. A lot of intelligence goes into reading a score, and this is often underestimated. High accuracy also requires the system to reconstruct missing elements where it can. For example a clef that is in shadow can often be deduced from the key signature.

You mention speed, and I agree that speed of processing is very important. This might not be immediately obvious. The reason is that many of the things one does in the course of using the app (like recapturing a page) require the music or parts of it to be reprocessed. The early stages of OMR can be done page by page, but the more subtle parts require the score to be processed as a whole – key and time analysis for example. This means that unless processing is very fast the user is left waiting about watching the progress bar. The next iOS release of PlayScore 2 will make use of all the processor cores on your device in parallel. This is something we have wanted to do for a long time. We find it reduces the time taken to process a PDF to about a quarter – from a page a second to 3 or 4 pages a second.

One big challenge is to increase the range of material PlayScore will accept. The immense variety of engraving styles in the world’s music is a big challenge. From beautiful urtext editions to miniature scores from the 50s, from old-style hymnals to Wagner vocal scores, they are all different; and each with its own problems. In recent years we have seen more and more music engraved using modern score writers. Score writers like Dorico produce very clear notation, but some of the lesser known ones (and there are many, particularly in China) produce poor output that can be a real challenge to decipher.

The biggest new feature in the next iOS release will be text handling. This means lyrics, directions and so on are extracted from the score and will appear in Dorico when you import the MusicXML. There are some spinoffs that also come with text recognition such as multi-bar rests and metronome marks.

DS: Thanks for taking the time to talk with me, Anthony!

You can find out more about PlayScore 2 at its web site, or you can download it from the App Store (for iPhone and iPad) or the Google Play Store (for Android devices). PlayScore works beautifully with Dorico for iPad, but you can also send MusicXML exported from PlayScore to your Mac or Windows computer and then open those files in the desktop version. It’s definitely worth your time to investigate and give it a try.

Your app does not do very well with Jazz that’s for sure. And that is a shame because it means your software will mostly be confined to the realms of classical and folk music. Introducing swing or latin variations into the app in a meaningful and authentic way would be impossible I think.

Thanks, Dallas Selman

As we say on our site. PlayScore 2 does not at the moment support music fonts designed to look handwritten.

This is not because we don’t want to. As I say in the interview we are constantly expanding the range of PlayScore 2 and that includes jazz fonts. Apologies It will come as soon as we can.

Both you and the great Elaine Gould have resolutely ignored chord symbols and chord diagrams. Are you contemplating making any headway into this difficult, but much desired, field of study?

The next release of PlayScore 2, due for release this year supports lyrics and text. It will also pick up most chord symbols. This will improve over time.