This post is part of a series that aims to shine a light on projects in which Dorico has played a part. If you have used Dorico for something interesting and would like to be featured in this series, please let me know.

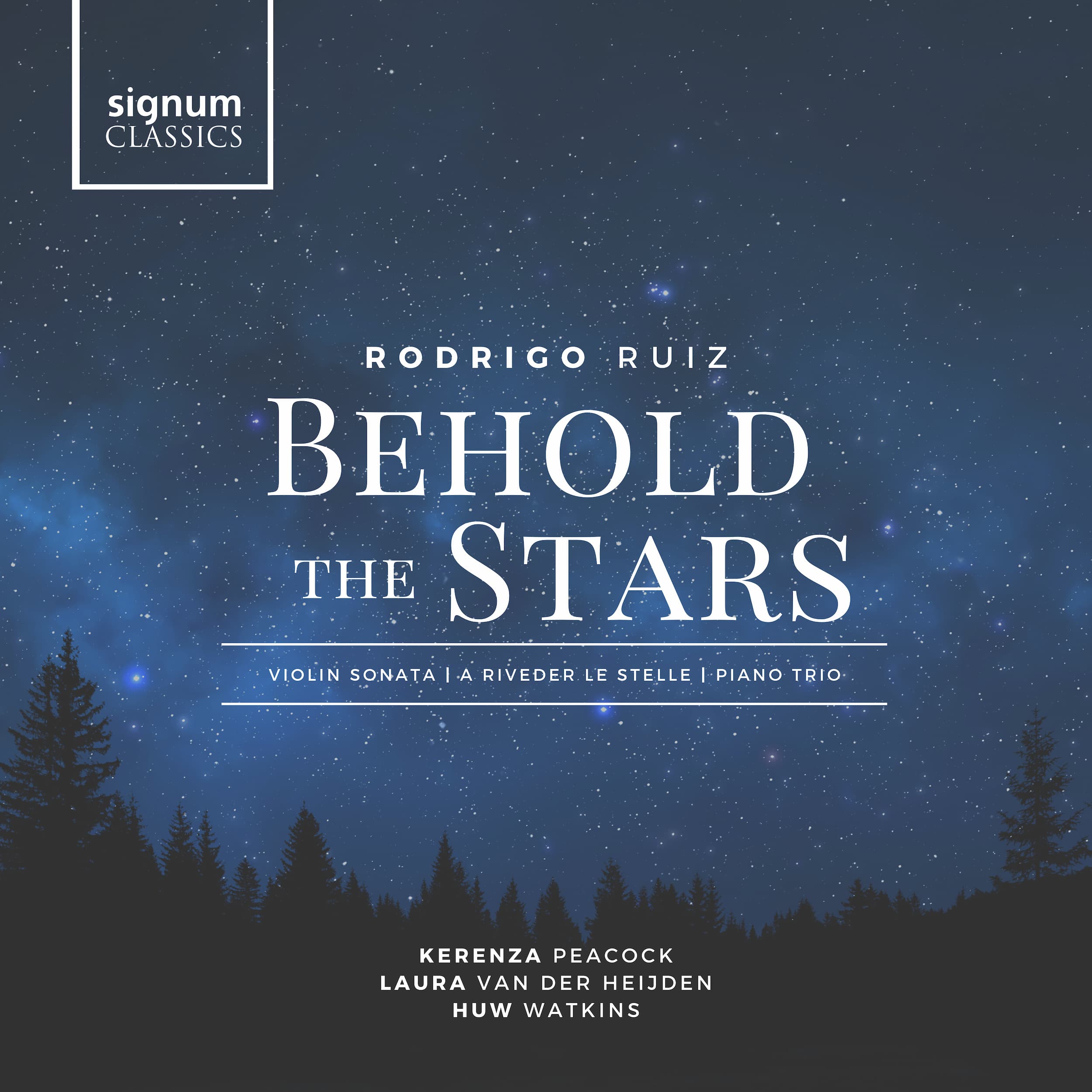

Rodrigo Ruiz is a Tijuana-raised composer and conductor who today makes his home in Rome, though like countless people in this strangest of years he found himself displaced and unable to travel at the beginning of the pandemic, back in his native Mexico, and ended up staying there to ride it out with his family. Just a few months before the pandemic closed down more or less all in-person music making, Rodrigo had been in the UK recording the pieces that make up his new release on Signum Classics, Behold the Stars, with violinist Kerenza Peacock, cellist Laura van der Heijden and pianist Huw Watkins. All of the pieces on the album were completed in Dorico, and I caught up with Rodrigo in the week of the album’s release to find out more about the project.

DS: The works were recorded in the Britten Studio in Suffolk, UK, in January of last year that must seem as long ago to you now as it does to me. Were you able to attend the recording sessions yourself? How was it as an experience?

RR: Yes, I was there. It was a truly humbling experience as a young composer to be working with such a star-studded team. Snape Maltings is a special place, not only for its history and British charm but also because the whole recording team gets to be together in beautiful natural surroundings. We all have to stay at the premises, which means we have lunch, tea, and sometimes even dinner together. This affords us plenty of opportunity to bond. We enjoyed some brisk walks in the windy but beautiful area, and we finally celebrated with legendary fish and chips!

Composer and conductor Rodrigo Ruiz (photo courtesy of Paulina Vallejo)

DS: Have these works been premiered to an audience, or is the new disc from Signum their first outing?

RR: Behold the Stars is their first outing. We were lucky that the recording sessions barely missed the beginning of the pandemic. But the performances we expected to get in had to be postponed indefinitely, like many others. We still hope to be able to premiere the works live sometime soon.

DS: You wrote these pieces at the request of your friend, violinist Kerenza Peacock, and she asked that you used a scordatura tuning for the sonata. How did this affect the writing of the piece?

RR: I think the way it happened was that I showed Kerenza an initial musical idea in F minor and mentioned the possibility of transposing it to G minor to use the bottom open string. But we both agreed that F minor was the right tonality for it, and at one point or another the scordatura seemed the perfect solution to it. Coming at such an early point in the creative process, this feature really became part of the DNA of the work—of Das Thema, as Beethoven would say. There are obvious differences: new double stops become possible, others become gnarly exercises for the violinist; some natural harmonics are lost, others are gained; two more semitones become available in the bottom register to play with. More importantly, it’s hard to resist the urge to “justify” having the scordatura by using the low register a lot more than you otherwise would. You really run the risk of sinking the violin down in the depths. Finding a balance became easier once I realised just how much the rest of the strings reacted to that whole-step change in the bottom register, how the entire range of the instrument completely changes colours. The darker hues the scordatura brings to the work really became a part of the Violin Sonata’s sound-world after that.

DS: The liner notes for the disc include your own English translation of Canto XXXIV from Dante’s Inferno, from which is taken the title of the album and of the second piece commissioned by Kerenza Peacock – A Riveder le Stelle, or Behold the Stars. I know that literature and myth are very important to you. Which came first: the music or Dante?

RR: Before writing this particular work, I was already utterly fascinated by Dante’s opus magnum. That’s why you could say the text came first—and certainly from a purely historical point of view Dante clearly came before this piece. This is, however, like the chicken or the egg. It’s impossible to know which came first. Does it matter, though? If you have a chicken, you can get an egg; if you have an egg, you can get a chicken. This realisation is essential to any composer because it means you no longer have to worry about starting from the beginning, as it were. You learn to take whatever comes first and then to work through that until, from that part, you perceive the whole.

From left to right: Kerenza Peacock, Huw Watkins, Laura van der Heijden (photo courtesy of Rodrigo Ruiz)

DS: The trio you assembled to record this album is wonderfully starry in its own right! What was it like to work with Kerenza, cellist Laura van der Heijden and pianist Huw Watkins?

RR: Very exciting! When you’re working with musicians of this calibre, you get to hone every little detail. These are musicians that love what they do, and they do it amazingly well. When you think they’ve just nailed the take, they want to push harder. And guess what? They can surprise you time and time again, reaching new heights with their musicality and artistic passion. Not only did we have an incredible array of talent in front of the mics, but also behind them, in the control room. I was fortunate to share desk real estate with the legendary Nick Parker and Mike Cox. I’m deeply grateful to Signum Classics for providing me with such a heavenly host of musicians.

DS: You composed the pieces for this album between 2017 and 2019. Did you use Dorico for all three of them?

RR: When I was in the middle of digitalising my sketches for the Violin Sonata’s first movement into Sibelius, which I had been using for a very long time, I heard about Dorico and decided to take the plunge. As you know already from our interactions in the forum for the past years, I quickly became a huge fan. I can truly say there’s a Before Dorico (B.D.) and After Dorico (A.D.) for me. The rest of the sonata, and the other works on the album, were all written with Dorico entirely—I still use pen and paper for sketching up to a certain point, however.

DS: Were there any features of the software that you found particularly helpful as you developed the works?

RR: Where should I start? It’s incredible that a feature that dealt with one of the most fundamental components of Classical music notation (a.k.a. movements) was not found until Dorico came along. You have no idea how much easier flows make my composing life. Now I don’t dread setting my movement orders before I’m entirely sure about them because it’s as easy as click-and-drag to reorder them anyway, anytime.

The management of layouts and the creation of parts is very intuitive and flexible as well. Besides the obvious, it’s advantageous when dealing with orchestral works, which can quickly become very hard to handle. For these works, I’ll create new layouts for each orchestral section (woodwinds, brass, percussion, strings), allowing me to orchestrate in parts. I also have a flexible layout where I’ll activate any instruments I need for the passage at hand, and then change it for the next. That way, I’m never at the mercy of screen real estate.

Dorico often “thinks” as a composer would. When I’m in the middle of the creative process I never dabble with engraving issues. That would completely distract from capturing the ideas that come and go swift as the wind. Dorico works the same way: the Write and Engrave modes are separate from each other, which makes sense within the context of my compositional workflow. It has also saved me more times than I can count from accidentally changing notes, dynamics, and other markings without intending to do so. In the end, that loses you time—and if you don’t catch it before rehearsals, that could be quite an expensive mistake.

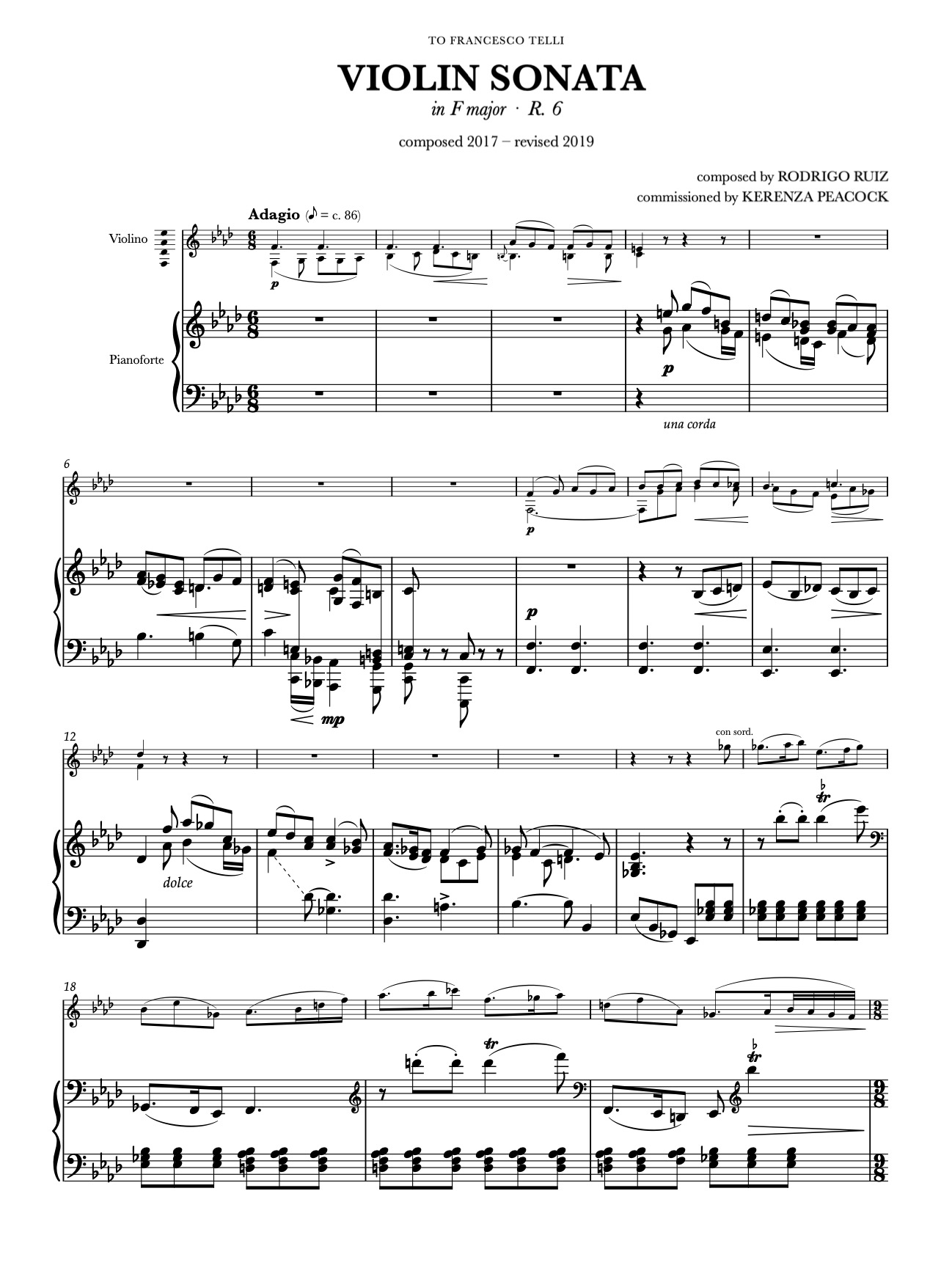

Adding the scordatura on the score was fairly easy—certainly a lot faster and easier than on any other notation software I know—but I must admit that it’s probably something that could be streamlined even more in the future. And, if I know the Dorico team at all, they’ll come up with a revolutionarily simple solution.

The UI design is sleek and easy on the eyes, which may seem terribly superficial to say, but it’s a huge deal when you’re spending that much time in a digital environment.

With software as advanced as Dorico, there’s no way I could ever remember how to do everything it’s capable of doing. Having a community that’s so supportive on the forum and social media is absolutely crucial. And the team are incredibly responsive. Having you and the rest of the Dorico team respond personally to a lot of our questions was, to me at the time, unthinkable. I’ve become so accustomed to it and to all the resources readily available that I don’t know how I managed B.D. Thankfully, we’re now living A.D. and happy not to have to look back!

The first page of the score for Rodrigo Ruiz’s Violin Sonata in F major

DS: What are you working on now?

RR: I’ve just finished writing a suite for solo cello. We have also been putting the finishing engraving touches to score and parts in Dorico for a couple of chamber works which should become available in the summer as part of Universal Editions’ scodo catalogue. (Leo Nicholson has been extremely helpful in this process.) In the coming months, we’ll also be recording Venus & Adonis, a song cycle after Shakespeare commissioned by soprano Grace Davidson. Next year, the album will come out with her and Joseph Middleton playing a McNulty 1819 Graf replica for Signum Classics.

DS: Thanks for taking the time to talk to me, Rodrigo, and congratulations again on Behold The Stars.

For more information about Behold the Stars, visit Signum Classics’s web site. To find out more about Rodrigo, visit his web site. If you haven’t yet tried Dorico for yourself, you can download and install a fully-functional 30-day trial version from the Steinberg web site.