This post is part of a series that aims to shine a light on projects in which Dorico has played a part. If you have used Dorico for something interesting and would like to be featured in this series, please let me know.

On 11 December, a concert performance of the score for the 1950 film The Last Farm in the Valley was staged by the Iceland Symphony Orchestra. This Icelandic film from director Óskar Gíslason, a folk tale which tells the story of a farmer who refuses to flee his homestead despite persecution by trolls, has a historically significant original score by composer Jórunn Viðar, but the film and its soundtrack have not been heard together for decades after the original soundtrack was lost. Composer Thordur Magnusson undertook the challenge of restoring the original score so that it could be performed with the film for this concert performance, and recently I talked to him about the process of bringing this music back to life, a project that was some 15 years in the making.

Composer Thordur Magnusson

DS: I understand The Last Farm in the Valley is quite a significant film culturally in Iceland. What can you tell me about it?

TM: The subject of the film is in the spirit of old folk tales, classic adventures featuring the battle between good and evil. It is set in the countryside where all of the farmers have fled because of persecution by trolls. One farmer remains with his family, however, as the grandmother possesses a magic ring that protects them from all evil. The trolls try to steal the ring from her, triggering a series of events involving supernatural beings, including an elf queen and a dwarf who can make himself invisible. Jórunn Viðar’s folk style is uniquely suited to the subject.

Stills from The Last Farm in the Valley

DS: How did you got involved with the score for this film?

TM: About 15 years ago, I got an assignment to write down part of the music from The Last Farm in the Valley. The music, written by Jórunn Viðar, was the first full-length movie soundtrack composed in Iceland. It was presumed at the time that the score and parts were totally lost so I was asked to transcribe the music from one of the scenes in the film and it was to be played in a concert. After finishing that, I felt somehow morally obligated to write down the rest of the music as I found it rather unfortunate that it was lost, but also because I found this music to be very interesting. I personally share with Jórunn the same enthusiasm in Icelandic folk music. I wrote down the rest of the music but left it un-orchestrated and unfinished. I did however finish a concert suite where I used the the themes and the material freely in order to compose my own version of the music, similar to what Stravinsky did in Pulcinella.

DS: You were the natural choice to assist the ISO in preparing the score for a full performance along with the film, then.

TM: A year ago, I was informed that the Iceland Symphony Orchestra was planning to have the film shown with live accompaniment to commemorate the centennial of Jórunn’s birth on 7 December 1918. At that time I was also informed that in the meantime some of the instrumental parts had been found. When I received them I found them to be roughly 60% of the music, but the score itself was still missing.

By combining what I had written down from the original masters and the newly discovered parts I was pretty sure that the score was by now in its original state as it had been written by the composer Jórunn Viðar, almost 70 years ago. I then started to compare it with a copy of the film – which I hadn’t seen since I was a kid – and discovered that something had gone terribly wrong when setting the music to the film. I was then informed that the audio portion of the film had been lost and the current film was a remake, where the music, along with other things, had all been messed up.

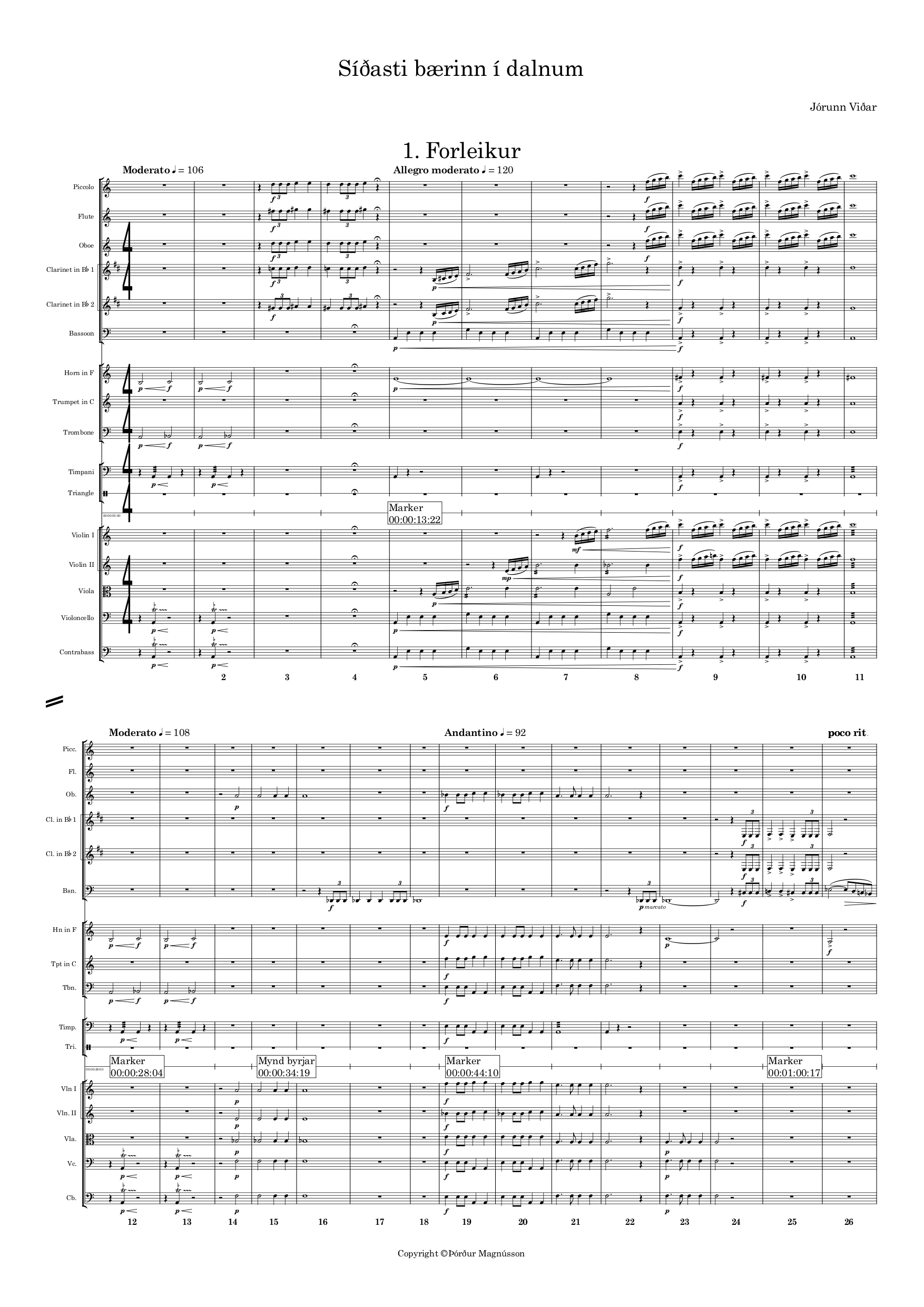

The first page of the full score.

DS: It sounds incredibly daunting to try to reconstruct the score to a 90-minute film without access to anything but the original soundtrack release and some incomplete parts!

TM: I knew roughly from the rebuilt score in what orders the tracks were supposed to be but there was no information as to where each musical segment belonged. By studying the film and the music I was able to identify how it probably had been conceived by the composer. What I did in this process was to import the film and the master tracks into Cubase and painstakingly trying out multiple different possibilities. It was actually made possible, though not exactly easy, by Jórunn´s amazing precision. A lot of the music was just spot on when the starting position had been established, whereas some parts of the music called for more work and even imagination in my part.

When this was finished I resumed my work in Dorico, imported the movie and started moving things around. Dorico made this part very easy and even fun by its clever handling of flows and the brilliant system track. I also worked out the tempo track to enable precise markers for the conductor. The original score was 50 cues/flows: in the end, the score as performed by the orchestra to accompany the film totaled 68 cues/flows.

DS: Were any features of Dorico especially helpful in allowing you to complete this project?

TM: With complicated project like this, Dorico was such pleasure to work with. Automatic multiple flow headings on every page made the parts very easy to make and also easy for the players to follow the film. The score itself made use of all the features like big meters markings and a special tempo track system. Dorico enabled me to make the huge score – more than an hour of music – in a blink of an eye and I was therefore easily able to experiment with all kinds of different possible layouts in order to fit it in the most convenient way and to suit the occasion. The conductor Bjarni Frímann, who by the way did a brilliant job, was most content with the end result.

DS: Thanks for taking the time to talk with me about The Last Farm in the Valley, Thordur!

A re-release of the film with the restored soundtrack is now under consideration, so it may be possible for this film to re-find a wider audience. If you would like to find out more about Thordur Magnusson, visit his web site, follow him on Facebook, or listen to his music on SoundCloud. In the meantime, if you haven’t yet tried out Dorico Pro 2, there’s never been a better time: you can download and use the software completely free for 30 days from the Steinberg web site.