This post is part of a series that aims to shine a light on projects in which Dorico has played a part. If you have used Dorico for something interesting and would like to be featured in this series, please let me know.

Gavin Gamboa is a Los Angeles-based composer, pianist, and video-artist interested in the intersections of improvised and premeditated composition. Born in Mérida, Yucatán in 1984, he currently composes for a variety of concert ensembles, creates film music, and performs classical/contemporary works internationally. He is one of the creative directors of The Teaching Machine, a media arts collective focused on audio-visual live performance. He has designed and performed video content with Erykah Badu, José James, Strangeloop, RYAT, and Nick Murphy, among others. His music has appeared in works exhibited at The Getty Center Los Angeles, Primavera Festival Vienna, MALBA Buenos Aires, Międzynarodowe Spotkania Teatrów Tańca in Lublin, Poland, Kunsthalle Basel Switzerland, The Downtown Independent Los Angeles, and Teatro Ángela Peralta, Mazatlán.

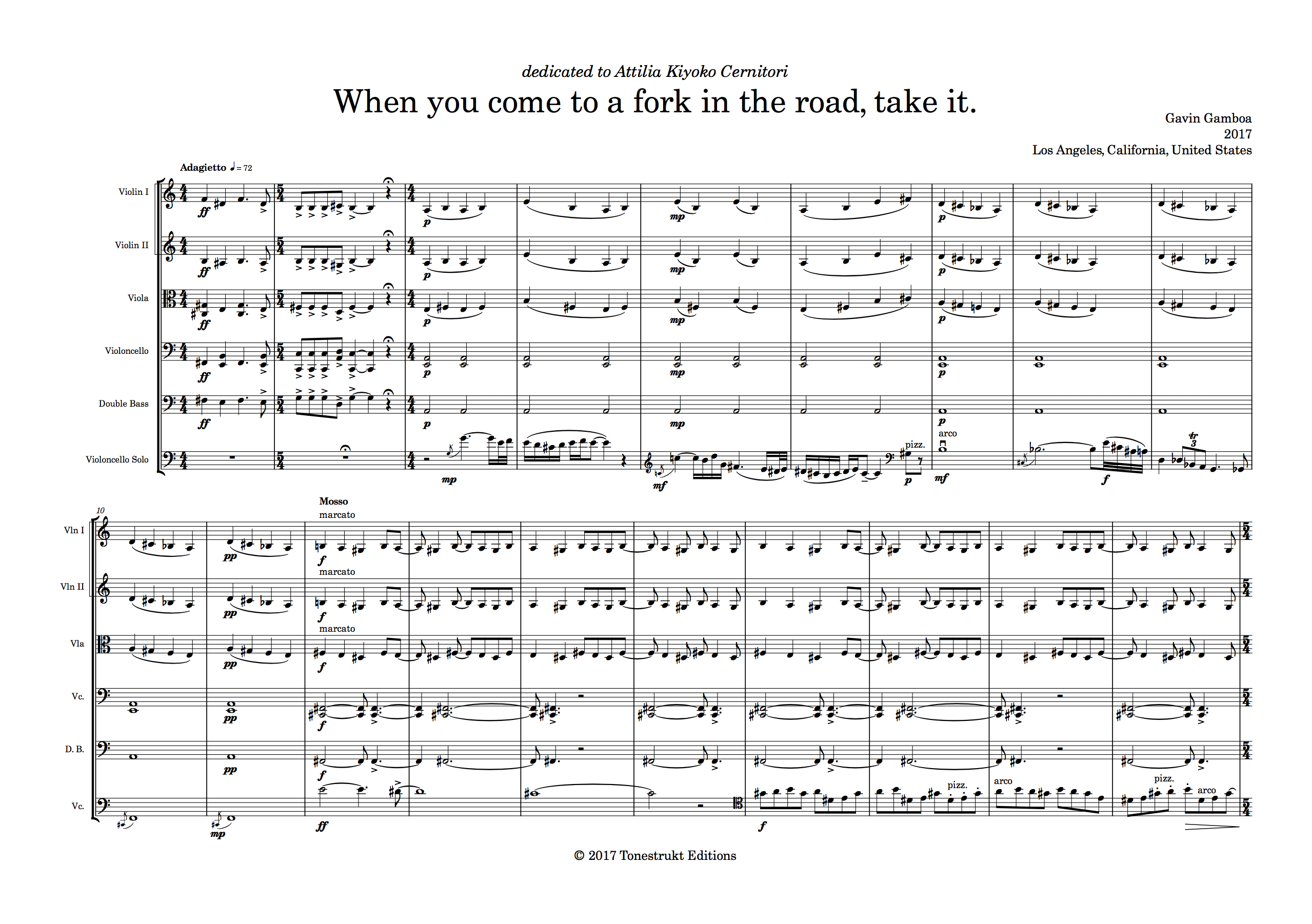

I met Gavin at the NAMM Show in January this year, and was fascinated to hear about the many different strands to his work. Recently he got in touch to tell me about the concerto he wrote for cellist Attilia Kiyoko Cernitori, which was composed from start to finish in Dorico.

Composer Gavin Gamboa.

DS: Tell me about how you came to write When you come to a fork in the road, take it.

GG: I met the cellist Attilia Kiyoko Cernitori through the Austrian-Mexican tenor and artistic director León de Castillo, who is a friend and collaborator of mine based in Vienna. Through one of our recent projects I came to know and work with Attilia while making a recording of one of my pieces at the University Art Museum of California State University Long Beach, as part of their exhibit on David Lamelas’ work for Pacific Standard Time LA/LA. Some months afterwards, she wrote to me about a concept she had for a concert with the Johannesgasse Solisten, a chamber group based in Vienna that she had been working with as a conductor and soloist, and for this particular concert the theme designated was Aus der neuen Welt – “from the new world” — and I was one of many composers she reached out to in order to build a program of works from North and South America. This was early December when she asked, and the concert was to take place at the end of January.

I was thrilled but slightly on edge about the whole thing! Not only did I not have a piece compatible for her ensemble already written, but I wondered if I even had the time to compose something new under those constraints. Part of this edginess came from memories of working with other notation software which, given my methods, usually would have me producing preliminary sketches on paper, then inputing those written pages into software. Finally, the laborious process of adjusting everything to optimal legibility of the full score and parts. I always found composing directly into software cumbersome and uninspiring, and paper/pencil to be effective, enduring, and essential to my practice.

I had already purchased Dorico – which was at version 1.2 at that point – but hadn’t really sunk my teeth into it. So I decided to skip my normal paper-sketch phase and compose a new work for Attilia and Johannesgasse Solisten directly into Dorico and see what would happen, even if that meant that I wouldn’t meet her deadline.

DS: It’s quite a tall order to both compose a new work and learn a new software tool in less than two months. How did it go?

GG: To my great delight, Dorico did almost everything I wanted it to do, and extremely intuitively. I finished the bulk of the gross compositional aspects of When you come to a fork in the road, take it., a work for cello soloist and string orchestra, in a matter of days, with some additional days used to make edits, redactions, and fine-tune the score. I especially found tools like lengthening or shortening phrases or selections of notes by the specified grid value extremely useful and novel as a compositional aid. The keyboard-centric interfacing with all aspects of the system, especially the popovers, is just such a time-saver and powerful way of working with Dorico.

Getting Attilia the score, all six parts, and an audio export of Dorico’s playback for her reference was a streamlined process with no headaches. While I had to make adjustments to the parts by way of choosing optimal system breaks, I never had to adjust that many additional objects like dynamics, slurs, accidentals, hairpins, playing technique text, notes, beams, and so on. That is something I would waste lots of time wrestling with in my former notation paradigm. When it comes to the visual presentation of my music I am extremely fastidious and discerning! But everything Dorico produced was to a high standard of legibility with appropriate spacing.

The first page of “When you come to a fork in the road, take it.”

DS: I understand you weren’t able to be in Vienna for the first performance, but did you get any feedback about how it went?

GG: At last, nothing could match my joy upon receiving the video of the performance that Johannesgasse Solisten and Attilia gave in January. It was almost too unbelievable! Here they were performing with great skill and ability a piece that just a few weeks prior I had questioned being able to deliver. For sure I would have struggled to achieve this result with such speed and fluency using the software I had been accustomed to. This experience gave me ample justification to migrate over to Dorico for all future notation projects. I should tell you that I am already putting Dorico Pro 2 to great use, and I would like to extend my thanks to you Daniel, for taking the time to hear about my story, and to all the development team at Dorico and Steinberg for delivering such an impressive product. I’m looking forward to what’s to come as the software matures and how it will shape our behaviors and demands as users, composers, arrangers, copyists, editors, performers, or even those curious about notation who want to explore its deep possibilities with relative simplicity on the front-end.

Attilia and the Johannesgasse Solisten in performance.

Thanks to Gavin for taking the time to share his experiences of working with Dorico to write his concerto. If you’ve not tried Dorico for yourself, there’s never been a better time: and you can download a free, fully-functioning 30-day trial version from the Dorico web site.