This post is part of a series that aims to shine a light on projects in which Dorico has played a part. If you have used Dorico for something interesting and would like to be featured in this series, please let me know.

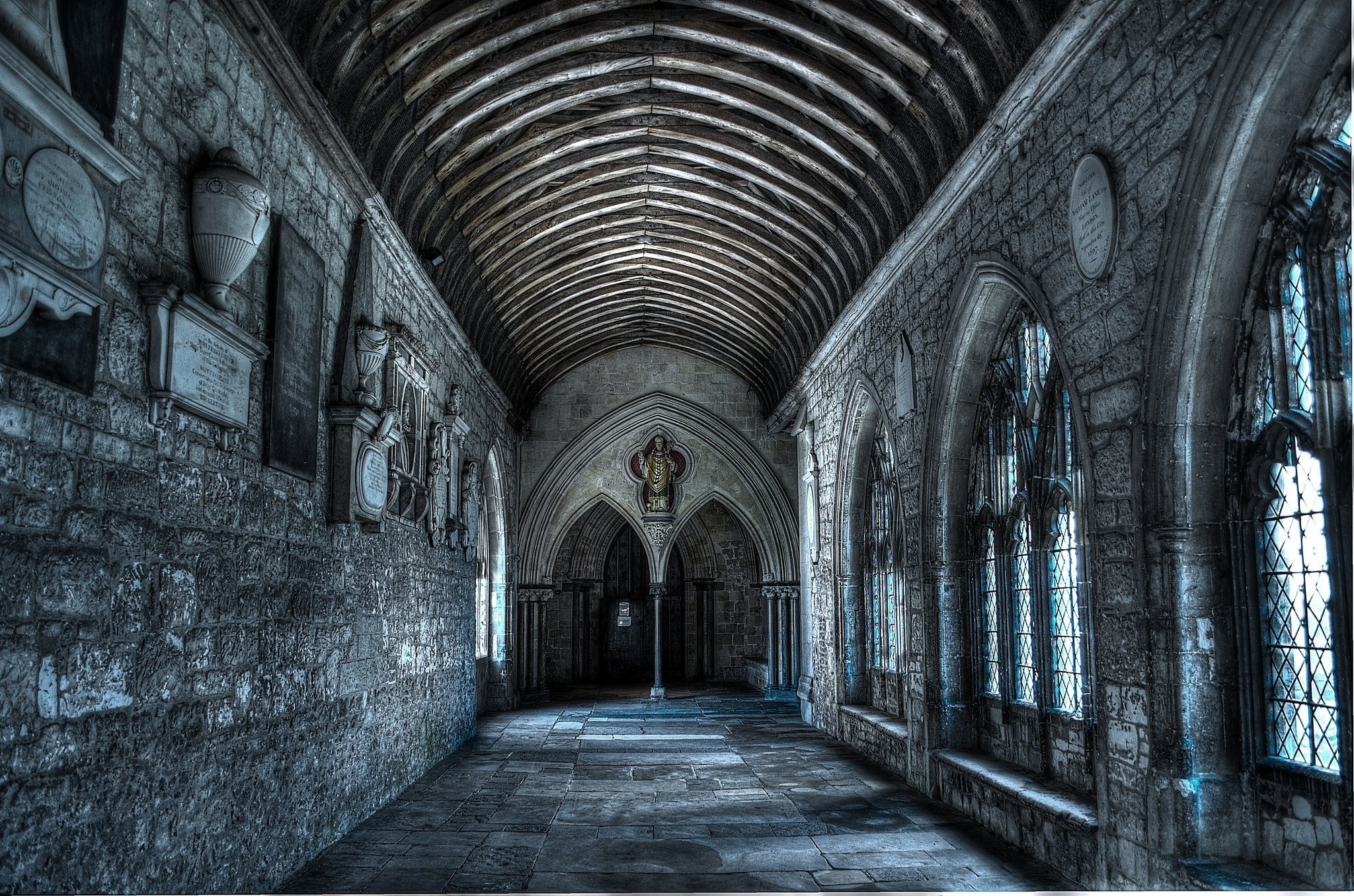

Chichester is a cathedral city in Sussex, on the south coast of England. With its cathedral dating back to the 12th century, it is one of dozens of similar cities around the United Kingdom with a long history of religious devotion, and religious music. Chichester Music Press is a publishing house founded in the city, run by Neil Sands, a composer, singer, organist, programmer, music typesetter, and, of course, proprietor of a publishing house!

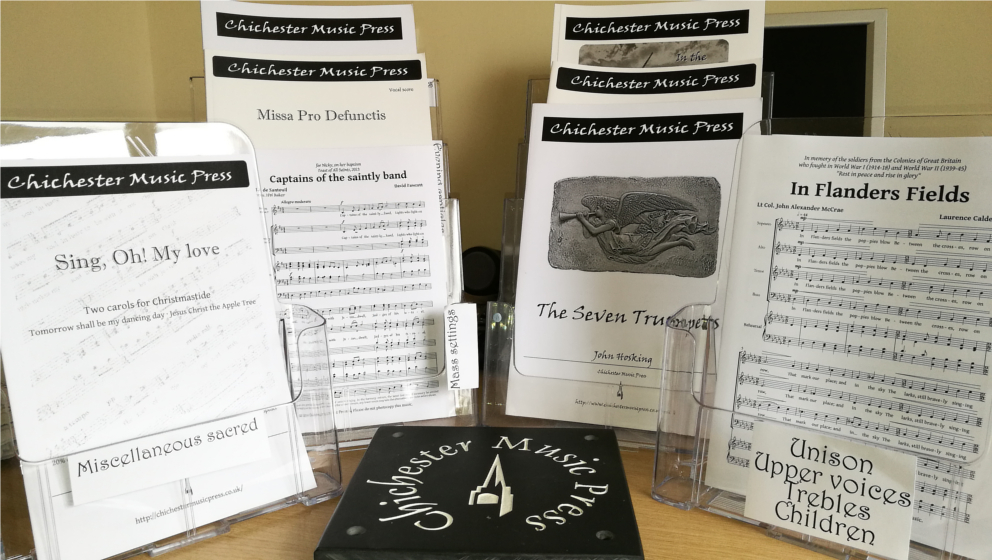

Chichester Music Press’s catalogue already contains two works typeset in Dorico, so I wanted to find out from Neil how he has found using Dorico for publishing so far.

DS: How long have you been running Chichester Music Press, and how many pieces do you have in your catalogue? Any particular favourites?

NS: I’ve been running the Chichester Music Press since 2003, when it occurred to me that if I wanted my own compositions to be published, I was going to have to do it myself. I already had the skills to build a functional website, and I’d been taught the craft of music typesetting during an 18-month apprenticeship. So it seemed a natural thing to do. Once I’d got myself established, other composers started asking to come on board as well, and to date there are about 200 pieces in the catalogue, mostly liturgical choral music.

I’ll limit myself to three favourites, chosen not because they’re ground-breaking or clever, but because they’re unashamedly beautiful. They are David Fawcett’s Magnificat & Nunc Dimittis setting, Christopher Larley’s Lumine for upper voices & tenor solo and, my absolute favourite gem of a piece, James Webb’s Blest are the pure in heart for unaccompanied SATB.

DS: Chichester Music Press has the honour of having added to its catalogue the first work originated in Dorico, on Dorico’s launch day back in October! You were able to do that because you were, and are, a beta tester for the software. Was it difficult getting John Hosking’s Ave Maria typeset in the beta version?

NS: No, it really wasn’t. Of course I had to learn how to do things in Dorico, which took a little time but it wasn’t too hard. In a sense it was like shooting at a moving target, because every new Dorico build added new features so more and more things became possible. I’ve been very impressed with how quickly Dorico has been becoming more and more powerful every few weeks. The final piece of the jigsaw was when Dorico got the feature to allow you to drag staves up and down – I must admit I went back and put some finishing touches to Ave Maria once that came along.

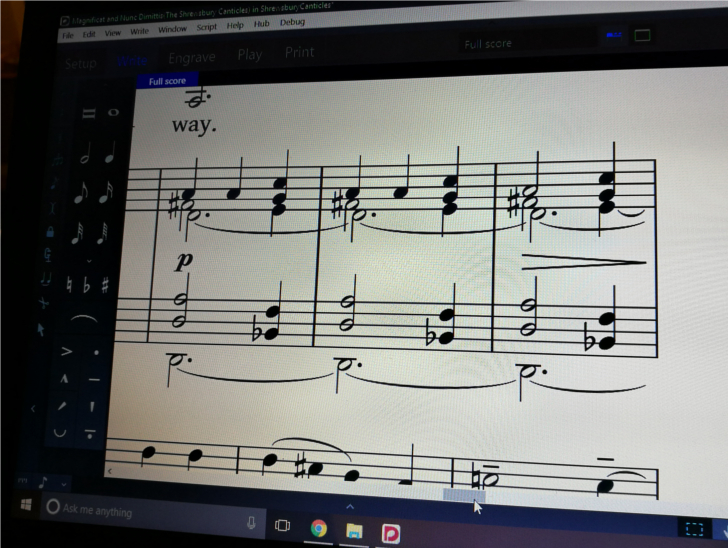

DS: The next work you have added to your catalogue for which you’ve used Dorico is the Shrewsbury Canticles by Benjamin Costello. What can you tell us about this work and its composer?

NS: Benjamin is an archetypal jobbing musician in that it’s a case of a little bit of this and a little bit of that. He’s fantastically busy here and abroad as an accompanist, adjudicator, conductor, singing teacher, music festival MD, university lecturer, and of course composer, and by the way he’s also a Freeman of the City of London.

His Shrewsbury Canticles is a setting of the Magnificat and Nunc Dimittis, which are canticles that form part of the daily Anglican liturgy of Evensong. There are literally thousands of settings of them, because they’re sung every day, and every cathedral choir will have several dozen settings they rotate through, so it can be several weeks before the same setting comes round again. However, the vast majority of these settings are for traditional SATB choirs. For other kinds of choir there’s a much smaller choice, and the Shrewsbury Canticles were written for the choir at Shrewsbury House School, and are for trebles only and organ. So they’re a welcome addition to the repertoire, suitable for school chapel choirs for example, or for school choirs who visit cathedrals to provide cover when the home choir is away.

DS: Did typesetting this score in Dorico present any specific challenges?

NS: The only thing that Dorico made tricky was to do with the handling of rests. Normally, if you have more than one voice sharing a stave, they share rests wherever possible, so you wouldn’t for example have a quaver rest in the soprano part and another at the same place in the alto part on the same stave. You’d use one rest for them both. Dorico has a setting for this that makes it very easy and you never really have to think about it.

But there is an exception to the rule – when you write for organ on two staves, and the left hand and pedals share the bottom stave, they’re supposed to keep their own rests even when they duplicate each other. And there’s no setting for that at present, so you have to handle it manually.

On the other hand, Dorico made easy work of some things which would have been a fiddle in Sibelius. Sibelius is very good at having two voices on the same stave (though there’s a longstanding problem where sometimes two notes in different voices will both move to avoid hitting each other and end up hitting each other). Add a third voice, though, and you’ll always have to shunt things about by hand to avoid collisions and to make the voicing clear. Well, the Shrewsbury Canticles has a passage where there are three voices going in the right hand of the organ, and Dorico just calmly and competently gets on with it. It’s right by default. No need to move any notes, and it’s obvious at a glance which notes belong in which voice. Really very impressive!

DS: How do you find working in Dorico more generally? I know you have been a Sibelius user for quite a few years now, so how have you found making the adjustment?

NS: I’m the kind of person who can go abroad and cope immediately with the traffic being on the ‘wrong’ side of the road, but then come back home and be utterly confused! And it’s a bit like that for me with Dorico and Sibelius. It definitely takes more thinking now for me to use Sibelius than it used to. I confess that I’ve set up Dorico keyboard shortcuts for the number pad to emulate the Sibelius F7 keypad layout, so 5 is a minim for me like it is in Sibelius, though I’ve left the top row of numbers as they are, so there 7 is a minim. And in Sibelius I now keep pressing space to move the caret on, only for playback to start!

Dorico and Sibelius think about the music in quite different ways; with Sibelius, you have to think the music into notation, so for example if you want a note that lasts four beats in a 3/4 passage, you need to use two notes tied over a barline. In Sibelius’s head, those are now effectively two notes, like they are on the page, even though you can’t hear the tie or the barline go by – you just hear one single sound. If you rebar the passage such that that barline disappears, those two notes remain as two tied notes.

But in Dorico, you can just think of it as one sound that lasts four beats, and even enter it that way if you like. So you can put a semibreve into a bar of 3/4 and Dorico will tie it over the barline for you. Rebar the passage and those two tied notes will reform into one if appropriate. I get a slightly childish kick out of being able to fill six 2/4 bars at once with one long tied note, entered as a dotted breve.

Dorico has a similar approach to rests. Unless you have something highly unusual going on, you don’t need to enter them at all. Dorico will put them in itself in between the notes you enter, and will group them according to the conventions of the prevailing time signature (and you can tweak those conventions in the settings). And that suits me just fine, because the rests are inaudible, just like barlines and ties are.

So now, apart from pressing the wrong button from time to time, I find I can switch between Dorico and Sibelius without any hassle by being mindful of their different approaches to entering music. If any Sibelius users are thinking of trying Dorico out but are worried about getting confused, I’d certainly say to give it a try. It’s really not too onerous a transition.

DS: Thanks for your time, Neil!

Check out both Jon Hosking’s Ave Maria and Benjamin Costello’s Shrewsbury Canticles on the Chichester Music Press web site. And if you would like to give Dorico a try, you can download a free 30-day trial version here.