When we finally announced Dorico’s name last month, and let you know when you will finally be able to use it for yourself, we were inundated with responses on Facebook, Twitter, on the new dedicated Dorico forum on our web site, and by email. Knowing that there are so many musicians out there waiting for Dorico and looking forward to adding it to their toolboxes is great motivation for us as we work hard to ready the application for release.

In the meantime, it’s time for another development update. I know that many of you are waiting for details about playback, and I will share some in (I hope) the next instalment of this diary. Our team in London and our colleagues in Hamburg continue to work very hard on the integration of Cubase’s audio engine with Dorico, but there is still much to be done. In this instalment, then, I’m going to tell you about Dorico’s page layout features, and also talk a little bit about lyrics.

Page layout

One of the areas in which we are trying to make Dorico offer unique and powerful functionality not found in other scoring programs is in page layout. Being able to quickly produce a stable and consistent page layout can be a challenge that tests the skills of even the most experienced users of scoring software. For example, page furniture (such as page numbers, headers consisting of movement titles or instrument names, plate numbers, and so on) must not interfere with the music, and the music must start and end in defined places on the page, whilst still allowing the flexibility that’s needed to handle exceptional circumstances (such as footnotes or critical commentary). We’re taking a new approach that has more in common with desktop publishing applications than it does with the existing mainstream scorewriters.

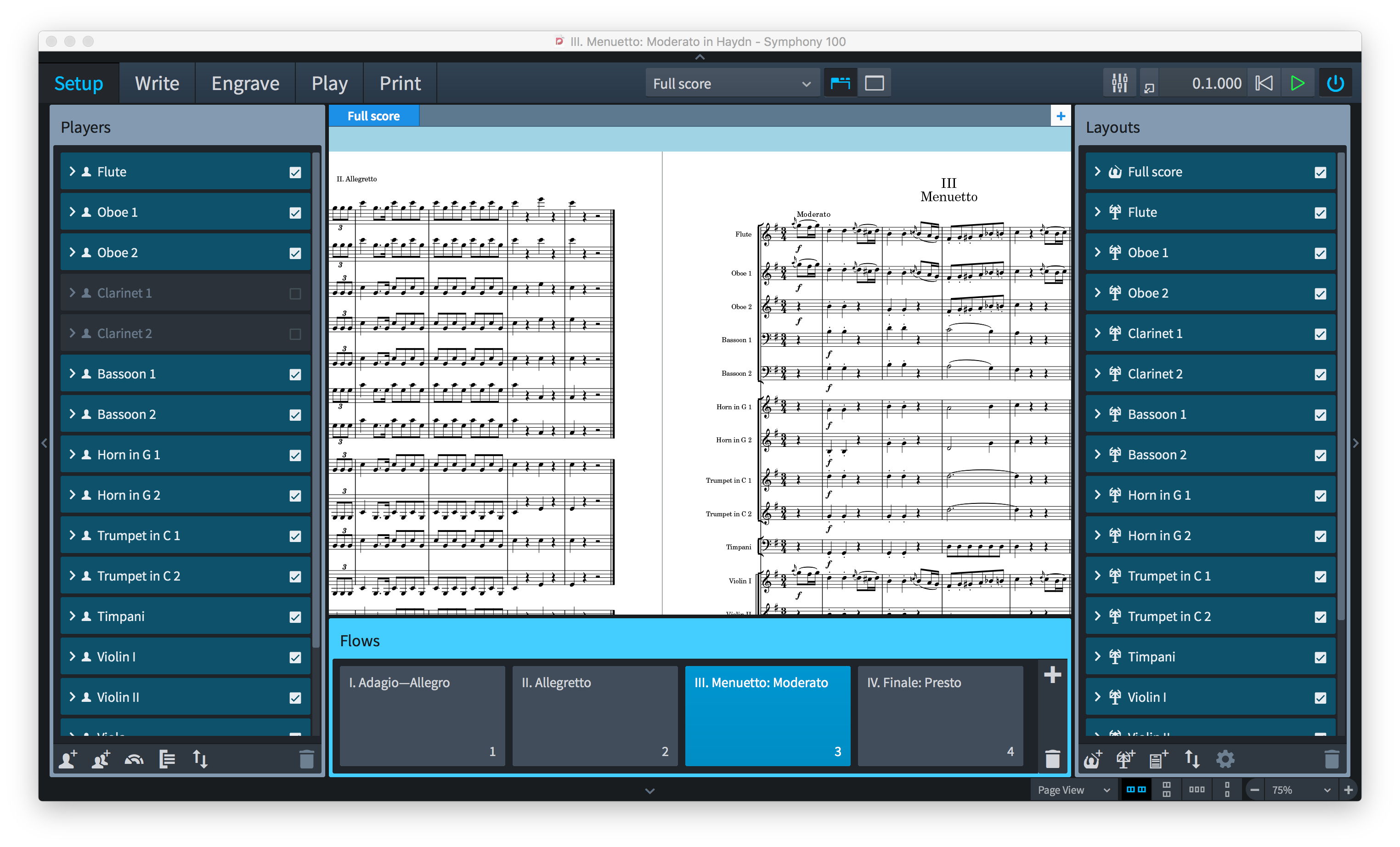

As I wrote in part 12 of this diary, Dorico projects can contain multiple independent pieces of music, known as flows, which can even be for completely different combinations of instruments, assigned to players, which represent the human beings who will ultimately perform your music in the real world. To actually bring your music into concrete, notated form that can be printed out onto paper or displayed on a device for a live performer to read, you bring together some combination of flows and players into layouts.

In a typical project, you will have a full score layout, which by default contains the music for all players from all flows, and you will also have a number of part layouts, which by default contain the music for a single player from all flows. You can edit which flows and which players are included in any layout, of course, if you need to. How each layout actually appears is controlled by a combination of the basic layout options, such as page size and margins, page orientation, and stave size (all of which are set in the Layout Options dialog, accessed from Setup mode), and the set of master pages in use.

Master pages

If you’re familiar with desktop publishing software, then you’ll most likely be familiar with the term master page, from where we’ve borrowed the concept. As the help pages for Adobe InDesign put it:

A master is like a background that you can quickly apply to many pages. Objects on a master appear on all pages with that master applied… Changes you make to a master are automatically applied to associated pages. Masters commonly contain repeating logos, page numbers, headers, and footers. They can also contain empty text or graphic frames that serve as placeholders on document pages.

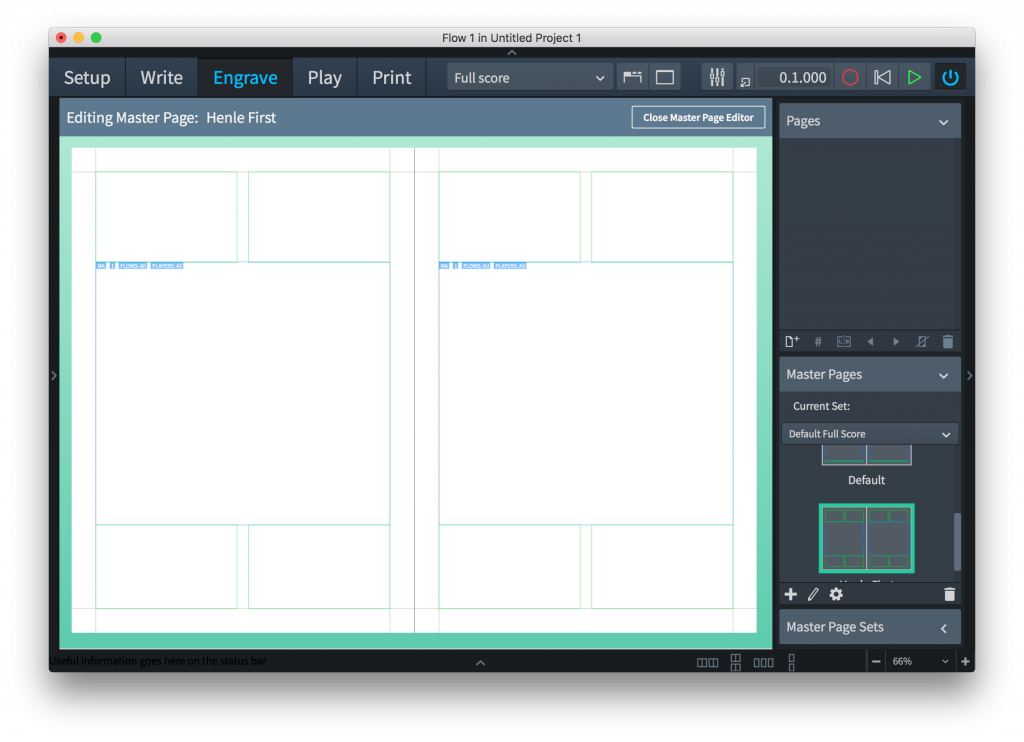

In Dorico, a master page actually consists of a pair of pages, one to be used if the page using that master page falls on the left-hand side of a spread, and one to be used if it falls on the right-hand side. The default master page set consists of two master page pairs: the default page pair, which is used for each successive left and right-hand page after the first page of the layout; and the first page pair, which is used for the first page of music in the layout. You can designate a particular page pair within a set as the special first page pair, but if no page pair has this special status, the normal page pair will be used instead.

A master page definition itself typically consists of a number of frames. Frames are rectangular boxes that can be positioned on a page, and then filled with content. In Dorico, there are three types of frame: music frames, into which the music chosen for your layout is flowed; text frames, into which you can either type arbitrary text, or choose from a number of tokens (sometimes called “wildcards” or “text inserts” in other programs), which are automatically replaced with preset information from elsewhere in your project; and graphics frames, into which you can load images in a variety of formats.

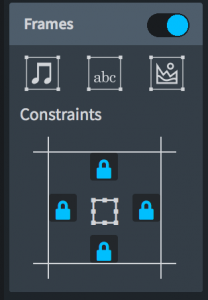

Frames can be positioned anywhere on the page inside the margins defined for the specific page size in use by the layout. All pages in a layout use the same page size, orientation, and margins, but frames can be laid out within those margins differently on every page, if necessary. Frames are defined in a manner that allows the page layout to adapt to changes in page size, orientation, or margins, so that the same master page definitions can be used for e.g. both A4 pages (as typically used in Europe) and Letter pages (as typically used in the United States), or even for A4/Letter and A3/Tabloid. In the language of the modern web, this is known as responsive design, and the behaviour of how a frame’s size and/or position changes when the page size or orientation change is defined in terms of constraints.

Constraint-based layout

You can think of a constraint as defining the relationship between one of the four sides of a frame, and the corresponding page margin. For example, a music frame that fills the entire height and width of a page, and which will grow or shrink as the page size or area defined by the margin is changed, has constraints on all four sides, all of which have an inset of zero, i.e. the edges of the frames should abut the margins.

A frame intended to contain a header, by contrast, would typically span the whole width of a page, so the left and right sides of the frames would be constrained to the left and right margins, with zero inset, and the header would also typically abut the top margin, so it would also have a constraint on its top side with an inset of zero. However, the header should have a fixed height, so it does not have a constraint on its bottom side. This means that as the page size changes, the top of the header frame will remain locked to the top margin, and likewise the left and right sides will remain locked to the left and right margins, but the height of the header frame itself will not change.

Once you have understood the basic concepts of a constraint-based layout, you can start to imagine the powerful possibilities this affords, particularly with a view to how music might be dynamically laid out when viewed on a device such as a tablet in place of a traditional paperbased music stand.

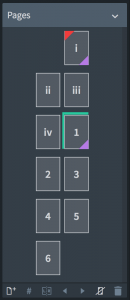

Overrides

By default, each page in a layout inherits from one of the master pages in the set used by that layout: the first page inherits the special first page pair, if present in the set, and subsequent pages inherit the normal page pair. If you edit these master page pairs, then the pages that inherit them will instantly update to reflect those edits, but you can also edit individual pages in the layout in a variety of ways, which creates overrides. Once a page is overridden, it will no longer automatically inherit changes made to its parent master page, until you explicitly clear the overrides, or specify that it should inherit from a different master page.

Why would you want to override the layout of a given page? Imagine that you are preparing for publication a critical edition of a new work, and it is your house style to include commentary in the form of footnotes at the bottom of some of the pages, as is the practice of publishers such as G. Henle Verlag. Most pages will likely have no footnotes at all, but some pages may require more than a sentence or two, and perhaps in more than one language (most of Henle’s editions today provide footnotes in three languages: German, English, and French). Those footnotes may need to include small excerpts of music, to show how a passage was reproduced in another source, or to suggest a possible realisation of an ornament, or similar.

Producing such a layout in one of the existing mainstream scoring programs can be time-consuming and awkward – to the point that many publishers prefer doing this kind of work either in a page-based illustration program, or in a desktop publishing program – but it is designed to be as efficient as possible in Dorico. Our goal is to eventually obviate the need for completing this kind of complex layout with the use of additional software.

To produce a layout like the first page of Beethoven’s C major piano sonata, Op. 53, as shown on Henle’s blog, in Dorico, you would simply drag the bottom of the main music frame on the page upwards to make room for the footnotes, then add two text frames of the same height, each occupying half the width of the page, and enter the text in the appropriate language into each box. To add the small musical excerpt, you could choose either to create a graphic frame and import the music in the form of a graphic (perhaps in a vector format like SVG), but much more fun and dynamic than that, you can add a new music frame and set its contents to an entirely different flow within your project: you could create a new flow for each footnote, edit it as if it were itself an independent piece of music, and then bring it into its own music frame, adjusting its stave size and spacing as needed to make it fit the appropriate space.

The possibilities afforded by having multiple independent music frames on the same page are practically endless: not only can you easily create footnotes, but you can create complex layouts of text and music for e.g. exam papers or exercise sheets, or create “fill boxes” that show how a guitarist or drummer might handle a particular solo or break. You can even produce, almost entirely automatically, the four-hands piano layout where Secondo’s music is shown on the left-hand page of a spread, and Primo’s music is shown on the right.

There’s so much more power and flexibility behind Dorico’s page layout engine. I’ve barely mentioned text tokens that can dynamically substitute information from elsewhere in your project, such as page numbers and movement titles; or the fact that text can be saved in text flows and shared between different layouts in your project (so you can use e.g. the same performance instructions in the full conductor’s score and a smaller rehearsal score); or the fact that you can easily insert blank pages anywhere in your layout; or import graphics onto a master page so that your company’s logo will appear automatically on the first page; or many other things besides.

Hopefully this brief introduction to Dorico’s page layout capabilities has sparked some ideas about how you might be able to use them in your own projects. Of course, if you just want your music to be laid out clearly, simply, and automatically, and you don’t ever want to edit a master page definition, the good news is that the program’s defaults are sensible enough that you never need to, but the power is there, hidden away behind a switch in Engrave mode, just waiting to be unlocked.

Lyrics

In vocal and choral music, we use the term “lyrics” to represent generically all text that is sung by singers – though in Behind Bars, Elaine Gould seems to studiously avoid the use of the word, instead referring to it as “the text,” which may well be a more accurate approach, since not all sung words in musical works would accurately be described as lyrics, as in either the modern usage of the lyrics to a pop song, or in the literary sense of referring to lyric poetry.

Despite its inaccuracy, it’s useful to be able to differentiate sung text from other forms of text that often appears in musical scores – such as performance instructions, tempos, dynamics, and the like – not only in discussions like this diary entry, but also in Dorico’s user interface, so we’re going to stick with it.

Inputting lyrics

Dorico’s approach to inputting and editing lyrics is hardly revolutionary, but it is efficient and hopefully comfortable. To get started, simply select the note or chord from which you want to start adding lyrics, and type Shift–L. In common with inputting other notations, a pop-over appears, with a read-out of the line number of the lyric you’re about to input. Simply type the word and hit Space to advance to the next note or chord, or if you are typing only one syllable of a longer word, hit – (hyphen) to advance. If you skip over a note or chord without providing a new lyric, hitting Space or – repeatedly will cause either a lyric extender line or one or more hyphens to appear, indicating that the word or syllable is to be sung over multiple notes. So far, so familiar, no doubt.

One nice advantage to using the pop-over to input lyrics rather than typing them directly onto the page is that the pop-over always appears at a legible size, independent of the zoom level of the score itself. You can always see what you’re typing, even if you have zoomed out to get more of the system or page in view.

You can have as many lines, or verses, of lyrics below (and indeed above) the staff as necessary, simply by hitting the down arrow key in the lyric input pop-over: the line number updates, and as soon as you start typing, the new lyrics are added to the new line. The distance between lines of lyrics, and indeed the distance between the staff and the first line of lyrics, can be controlled via the Engraving Options dialog in Engrave mode, and indeed there is a variety of other options relating to lyrics there, too, including the minimum distance between adjacent lyrics, the gap before or after, and between, hyphens, the thickness of the lyric extender line, and so on.

When a line of lyrics is missing across the width of a whole system, no additional gap is left between the remaining lines of lyrics: for example, if you typically have three lines of lyrics, but on one system the second line of lyrics is completely absent, then the third line of lyrics will be moved upwards, closer to the first line of lyrics; if on a subsequent system the second and third lines of lyrics are present but the first line is completely absent, the second and third lines of lyrics will be moved upwards such that the second line of lyrics is positioned vertically where the first line would normally be. Dorico can optionally print line or verse numbers automatically, too, immediately before the first lyric in a given line in a given flow.

One further neat trick up Dorico’s sleeve is that you can also designate either a whole line or just a selection of lyrics as being a chorus, which means that those lyrics are automatically written in another font style (by default, using the same font family and size as normal lines of lyrics, only italicised) and centred vertically relative to the existing lines of lyrics on the system where the transition between regular and chorus lyrics takes place. (No, Dorico doesn’t automatically show a curly brace or similar to denote the transition point between regular and chorus lyrics at the moment, but it may in future.)

Alignment and spacing

Although lyrics put pressure on the vertical spacing of the music, generally forcing staves further apart, they put much more pressure on the horizontal or rhythmic spacing of the music.

Firstly, there are the conventions for how lyrics are aligned relative to notes and chords. Single syllables (whether whole words or parts of longer words) that are sung on only one note are centred on that note; melismas, that is to say syllables or words that are sung on more than one note, are left-aligned with the left-hand side of the first note, to draw the singer’s eye rightwards towards the remaining notes to be sung to that sound.

Secondly, because lyrics are very often wider than the notes to which they are sung, there can be a significant impact on rhythmic spacing: a lyric on one note cannot be allowed to collide with a lyric on another note, so it is often necessary to widen the spacing, sometimes by a considerable amount, to accommodate lyrics, and if you happen to be unfortunate enough to have very wide lyrics (e.g. “screeched”, “strengths”, “straights”, etc.) on very short note values, you will most likely find that the rhythmic spacing is significantly distorted.

Gould allows that very long syllables do not have to be centred precisely under the note: she recommends that they are offset to the right, such that more of the word’s width is found to the right of the note to which it is sung than to the left. In practice, engravers prior to the age of computer engraving seem to have taken a less rigid approach to this problem, essentially allowing lyrics to shuffle either to the left or to the right if this allows a reduction in the amount of rhythmic distortion caused by using precise centre- and left-alignment strictly abiding by the letter of the law.

To date, no scorewriting software (to my knowledge) has attempted to make automatically the kinds of adjustments that human engravers used to make when typesetting lyrics – until now. Dorico is the first scoring software to automatically adjust the horizontal position of individual lyrics relative to the notes to which they belong, to minimise the distortion of rhythmic spacing.

The mechanism by which this is achieved is a general one that allows items outside the staff to contribute towards rhythmic spacing: this means that, for example, hairpins are never drawn so short that they look more like accents than gradual changes of dynamic; a tempo change followed in quick succession by a gradual increase or reduction in tempo in the form of a rit. or accel. will not collide with each other. In these kinds of situations, the rhythmic space is expanded to accommodate the minimum legal length for the item in question (such as the hairpin) or its actual minimum size (such as the text of the tempo change), over the rhythmic duration of the item.

Lyrics are nevertheless unusual in that they can typically influence the space allotted only to a single note at a single rhythmic position: if the same word or syllable is sung over multiple notes, it is typically left-aligned with the first note (opening up more space for a longer lyric to its left), and because there is at least one more note to come, there is typically enough space to the right to avoid increasing the rhythmic spacing in any case. But for a troublesome word like “strength” on a single note, it must be positioned relative to the note such that it neither collides with other words to its immediate left or right, nor does it stray too far under another adjacent note or rest that doesn’t have a lyric of its own for fear of introducing ambiguity over the true home for that word. At the same time, if possible, we want to avoid simply always adding rhythmic space for wide words and syllables: but if we move one lyric left or right in order to avoid adding space, we may introduce a new collision with an adjacent lyric, and end up in a vicious cycle of shuffling lyrics left and right in futility.

We are choosing to keep the exact details of how these concerns are balanced under our hats, at least for now, but the result is that lyrics are able to move subtly to the left and to the right to reduce the amount of additional rhythmic space that needs to be added to accommodate them, without introducing ambiguities in the underlay, and without causing collisions elsewhere on the system. The effect is subtle, but this is as it should be, in common with dozens of the other tiny details to which we have paid great attention as we have built Dorico, and in common with the similarly subtle and clever gambits employed by skilled human engravers over the past two centuries.

Keep control

In contrast to the subtleties of how Dorico adjusts the alignment and spacing of lyrics to produce a pleasing result, the way that it handles edits to the lyrics themselves is decidedly unsubtle, and usefully direct.

In other scoring programs, one of the annoyances of working with lyrics is that you cannot easily change the way the application thinks about a given lyric once it has been created – for example, if it turns out that a lyric ends up left-aligned when it should be centred under the note, because it has been copied and pasted from one staff to another. In Product A, for example, there is no option but to delete and re-enter the lyric to change how it’s aligned. In Dorico, by contrast, you can simply select the lyric, open the Properties panel, and change its syllable type, which will not only change its alignment as needed, but also fix up any extender lines or hyphens that are affected by the change.

It’s also easy to make larger scale edits, such as changing the order of verses: simply select a lyric in the line you want to move elsewhere, right-click, and choose the new line number. Any existing lyrics in that line number will be swapped with the lyrics you’re moving. You can also easily move lyrics from below to above the staff in the same fashion.

More to come

With that, it’s time to wrap up this instalment of the diary. Lots of other excellent work is going on in beaming, tremolos, ornaments, bar numbering, localisation, user interface, and, of course, playback, and I’ll touch on some of these areas in the next development update. In the meantime, we look forward to continuing to discuss Dorico with you both in the comments here and in the already pretty lively Dorico forum. Come and join us!

Very interesting stuff, as usual.

Thanks for writing, Daniel!

Congratulations on releasing Dorico! I am truly happy that there is a new scoring software out that brings it closer to dreams of any composer who deals with both worlds – acoustic and electronic. It seems that Dorico is getting closer to achieve a superior notation software and yet, it keeps the cries of many unheard… We want be able to use a quality scoring not only with VST’s but also with external synths and synchronize it with drum-machines, modular equipment etc. I know there is an idea that electronic music doesn’t require a notation, but to me (and many others) without a notation one cannot move into a world of more complex musical “structures”. Yes, there is Cubase, Logic etc.. but their scoring capabilities are limiting and writing music in notation in Cubase is just so tedious – compare to Sibelius etc. My solution was to run tracks from Sibelius via IAC virtual ports into other DAW.. but the connection is hard to set-up (in Sibelius)and it is rather very fragile while there are so many components to have it working smoothly (now again, it doesn’t work anymore).

Thus it is leaving us to go back to an old approach – to design a structure first, import it to a different DAW to “orchestrate/arrange&incorporate with the machines”. But Why we do not have a complete system that does it all? I beg you, please help us, so we can make a music for the new generations who are becoming forever stuck in four-bar 4/4 loops. A simplest solution for now would be to introduce Midi clock Send (or receive), so we can synch the other tools with DORICO. Another would be a possibility to route Dorico’s tracks (midi&audio) to external midi ports, audio and virtual ports. This would work just fine and I guarantee that if this solution would be stable (for example to interconnect Dorico with Cubase or even Ableton Live) – it would create such a revolution!

I think that unless we incorporate standard music tools more fittingly into an area of electronics and the machines, we will only further nourish this illusion of classical & academic music superiority versus modern “decadent” music. However the bank accounts of main-stream music producers show the opposite. I do believe though that classical music forms, the art of writing music, music story-telling and its vast beauties should be preserved and to built upon. I think it is our duty to step up with the game and to re-link the music of presence with the past otherwise the music’s history will eventually vanish into the oblivion. And so will do an attention span of our kids.

Sincerely,

Vlado Mudrak

Sounds great as usual!

How do lyrics react to the musical content being edited? For example, if an edit results in a half note being converted into two quarter notes split across a barline, does Dorico automatically add a lyric extender line?

@Ian: At the moment, the lyrics don’t move around when the music moves around. We’ve debated this issue a bit, along with similar issues relating to dynamics and other markings that are not technically part of the voice of the music itself, but are clearly related to it. In some cases you would want lyrics and dynamics to move around when you edit, and in other cases you would not. As the application matures I think we will be able to come up with some good workflows to address both possibilities, but I suspect in the first version lyrics will basically stay put unless you explicitly move them around. Having direct control over how the program thinks about them via editing their properties will prove to be very handy in sorting these kinds of things out.

Thanks, Daniel. I understand why sometimes you would want them to move, and sometimes you wouldn’t. Maybe having two types of insert mode would be an idea – a normal mode which just shunts the notes and leaves lyrics/dynamics etc. alone, and a “strong insert” which moves everything that is attached to the notes too. Just a thought.

Please take my money.

As a liturgical/choral composer, text was among the highest priorities for me. I absolutely love what I’m seeing so far, Daniel! Bravo too for the attention to the layout system; I’m a seasoned InDesign user, but I’d much rather do all the work in one app than two.

A few questions for you:

1. Will I be able to copy/paste text as lyrics?

2. Any auto-syllabification planned like Sibelius does? Will it understand what in God’s name to do with the word “people?”

3. What about lyric/text export?

Thanks for all your team is doing… Dorico is already winning me over.

@Tony: We probably won’t have copying and pasting of either pre-syllabified or non-syllabified text as lyrics in the very first version, though it’s something I hope we will do in the future. I think we would rely on a genuine hyphenation dictionary for automatic syllabification, since on the whole I think there’s a consensus that it’s almost never appropriate to use anything other than standard dictionary hyphenation (notwithstanding the pages that discuss this in Behind Bars). Right now you also can’t export lyrics as text, but hopefully that will be possible via our scripting API in due course.

Writing as another liturgical/choral musician, I too welcome the all-in-one-app approach; this will save many, many hours of fiddly work – not to mention remembering how it was done when I inevitably revisit the piece a couple of years later to revise it. My first big publishing project used Finale and PageMaker and my latest employed Sibelius and InDesign, which was a much more user-friendly setup. I look forward to working still more efficiently in Dorico. I hope that “floating” incipits and intonations will be easier too.

Thanks for all that you’re doing, and for this blog. My piggy bank stands ready.

Yes! never need to InDesign for page layout. Very nice feature that I did not expect. Well done Daniel and thank you for keeping us informed about Dorico.

@Daniel: Thanks for the prompt reply as always! Oh, well, I suppose you’ve gotta have something saved for 2.0… =)

SOLD! The lyric alignment ability to focus on individual syllables has been my top talking point with the Finale team for many years. Glad someone realized we really need this. I have so many lyric questions but will formulate an email and send. The layout concept seems solid. Master pages, finally! Will you allow a user to create and use (for lack of better words) “Paragraph Styles” that can be applied in real-time without going into a menu to apply or change via a floating pallet, similar to InDesign?

@Steve: I’m glad our approach to lyrics looks good to you. Text editing is still pretty embryonic at the moment, but the intention is certainly that you will be able to apply paragraph styles (and indeed character styles for runs of text within paragraphs) to text within text frames in a direct fashion.

So looking forward to it 🙂 What’s the minimum OSX it’s going to work on?

@Niels: We expect to officially support whatever the current version of macOS is available at the time of Dorico’s release, which I guess will end up being macOS 12 Sierra, but in practice we are testing it as far back as OS X 10.9 and it’s working fine there. The only real requirement is that your computer is running a 64-bit operating system, and I would recommend more than 4GB RAM.

Wonderful! Thank you!

How will vocal staves handle dynamics and the like, that needs to be placed above the music? Any automatisms? Or pre-configuration options?

@rowild: Dynamics will automatically be positioned above staves belonging to voice instruments.

It looks extremely sophisticated and full of latent possibilities. Enjoyed the little movies too. Wonderful stuff Daniel.

Thanks Daniel! Love these “under the bonnet” looks.

This is all looking great, Daniel, particularly the page stuff. Getting the first page to be a verso in Sib is such a faff, I’ve given up bothering. It’s nice to know this stuff’s being embedded in Dorico early on.

Daniel, where words are split up into four or more short syllables, as is often the case in German for example, engravers of yore used to omit hyphens wherever they took up unnecessary space. Try fitting something like “Göt-ter-däm.mer-ung” or “Schau-spiel-di-rek-tor” to a group of short-value notes. Hyphens would just get in the way. How will Dorico handle scenarios of that kind?

@Antony: Dorico would normally show hyphens in that case, but if you really want to suppress the appearance of a specific hyphen, you can do so by changing the Syllable type of a lyric from e.g. Start of word or Middle (which will cause a hyphen to appear, and space will be made for the hyphen too) to Whole word.

Brilliant!

Hi Daniel,

I’m actually a bit surprised and disappointed that your proposal is a non-semantic workaround, given how much effort has been put into making Dorico think about the meaning of the music. Does this imply that words are not even recognized, only syllables? I find that this issue comes up a fair bit more frequently that I would enjoy fixing the way you propose, and as a singer, the closer spacing that results is far easier to read. Instead, could there be an option among all the other spacing tweaks for collapsible hyphens? Say, give a minimum hyphen size and below that it just disappears?

@Jacob: Dorico’s understanding of lyrics is based around how they should be drawn in the score: it certainly doesn’t try to parse the words themselves in any fashion. The aim is to provide direct control over whether or not a lyric should show a hyphen or extender line, and whether it should be centred or left-aligned, obviously taking its default behaviour from the conventional way that lyrics are positioned and spaced, but with the option of overriding it if necessary. It may be a tiny bit semantically unclean to specify that a syllable that would normally be drawn with a hyphen is instead a whole word, but it produces the desired result without any practical downsides. I would not rule out adding “collapsible” or soft hyphens in future, but my determination is that the behaviour of e.g. Product A, which allows any hyphen to disappear if spacing gets tight, optimises for the rare case rather than optimising for the common case: in many languages, it would never be acceptable to allow the hyphen to disappear, and even in English, it is often not a very good idea. So Dorico does the right thing much more often, and provides very direct and simple control to override the behaviour when you need to.

Thanks, Daniel. I’ll hold out hope that as Dorico’s lyric handling gets more sophisticated this will be considered as an edge case worth supporting, though by no means necessarily the default. I’d think that if auto-hyphenation is to come along, there would have to be some back-end understanding of word vs. syllable anyway. To my mind, this could potentially alleviate other thoughts people have, such as the need to manually tell Dorico to add an extender to a tied note (which as you’ve shown in previous diaries is only though of as a single duration, not as the presentation of two notes tied). The fact that lyrics are handled on a presentation-first basis just seems odd to me.

Anyway, impressive work all around, and thanks for fielding the nits! 🙂

@Jacob: Lyrics have to be handled presentation-first, because otherwise Dorico has to have a semantic understanding of the lyrics themselves, which could be in any language. The semantics of music notation, while complex, are at least somewhat more limited in scope than the semantics of every spoken and written language on the planet!

Haha, oh dear, we’re talking semantics differently – point made! I mean like the “semantic web” where objects have meaning rather than just visual descriptors. I certainly don’t expect Dorico to understand the semantics of hundreds of languages!!

That said. 🙂 Lyrics in music function AS music, with arguably fewer rules than, say, beaming, no matter the language (in my experience, anyway – I’ve never seen variation in how lyrics are laid out across languages, but you certainly know more about that than I). I just don’t think that they’re only visual elements on a page of otherwise meaningful music. Abstracting lyrics into something that can be processed with the same degree of musical intelligence as notes doesn’t require any understanding of different languages (and really, the only thing it needs to do is know “word” vs “syllable”), but it does enable a whole host of features, such as:

-find and replace

-spell check in any available dictionary library

-auto hyphenation using standard hyphenation dictionaries (I’ll note that if you don’t recognize a word, you can’t hyphenate it)

-automatic melismatic slurs (configurable)

-automatic syllabic flags and beams (configurable)

-music following: syllables get assigned to rhythmic points so if you add note values in the middle somewhere the lyrics reflow just like everything else

-cloning: a common text (eg, in polyphonic choral music) can be entered once and assigned ad libitum to multiple other flows; edits made to the master propagate throughout

I’m probably misunderstanding what you’re saying about how things work, but if not, I hope this is food for thought.

Cheers

@Jacob: Lyrics in Dorico do have semantic information associated with them: what else is the syllable type (defining a lyric either as a whole word, or as the start, middle, or end syllable of a word) if not semantic information? And Dorico uses this semantic information to determine both the horizontal alignment and the presence or absence of hyphens and extender lines. Your wish list concerning things like find and replace, spell checking and hyphenation are, I hope you will forgive me for saying, absolutely nothing to do with the semantics of how lyrics are represented within Dorico, which is not to say that they would not be very useful features for working with lyrics in the program.

“in many languages, it would never be acceptable to allow the hyphen to disappear”

This. 🙂 I remember fighting for years on the *cough* Sibelius user forum about disappearing lyrics… Now there is an option “Engraving Rules / Text / Hyphens allowed to disappear when syllables are too close together”, which can be un-checked. (checked by default for some reason)

I’m holding my Sibelius 6 tight! It does everything pretty much exactly the way I want now.

* Lyrics and note spacing are easy to handle, and it’s very easy to manually balance lyric placement and rhythmic distortion by having “Note spacing rule / Allow space for lyrics” unchecked, and then selecting a passage and stretching it with Alt+Shift+arrows left/right. Either expand the tight passage with Alt+Shift+Right-arrow, or compress a not-so-tight passage with Alt+Shift+Left-arrow. Often it’s enough to squeeze an empty bar or rests a bit narrower, to give more breathing space to the overly tight note passage. 🙂

* Lyric verse beginnings with separate hanging verse numbers are quickly and easily lined up with keyboard shortcuts.

* I can type in “Legacy chord symbols” in Scandinavian style, H and Bb like they should be typed, in-place, and without trying to get the software to “understand” stuff any more than absolutely necessary. (the new non-legacy chords are a bad idea to begin with)

* I can add extra symbols to chord symbols! 🙂 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6qt-d6pGO3g

Maybe I should make a Youtube video showing how I use Sibelius 6. I’m not saying Dorico couldn’t possibly be better, it’s more like, I actually want it to be even better.

@Daniel: I have to agree that this is in stark contrast to your carefully thought-through approach for many other aspects. I’d like to suggest to add a property to “omit hyphen” to “Start of Word” and “Middle” syllables, instead of recommending a workaround that seems to go against the very system of Dorico’s understanding of lyrics. As you say yourself: “what else is the syllable type (defining a lyric either as a whole word, or as the start, middle, or end syllable of a word) if not semantic information?”; so, with these rather clear semantic categories in place to make decisions about presentation, what is the benefit of then overriding this and telling the program that something is a whole word when it actually is not? The syllable type should provide the default for hyphenation, determining if a syllable can or can not have a hyphen at the end; but it should not directly be used to set the actual hyphenation of a case.

In fact, I can even think of cases where syllables might need an option to enforce preceding hyphens. There are pieces where multi-syllable words of the text are distributed between different performers. Depening on context, it might be useful to have a preceding hyphen for those “Middle” or “End” syllables which happen to be the syllable of a multiple-syllable word at which a performer joins into performing that word. (Player one: “Po-“; Player two: “-ta-“; player three: “-to!”).

Talking of properties of lyric syllables: have you thought about other punctuation than hyphens? For example, I could see use cases where enclosing brackets would be more useful to be properties to be switched on and off instead of being part of the text proper.

Thanks daniel, it is really encouraging to see you are adressing lyric collision. Can i ask you about voices, in something like o for a thousand tounges, where the parts split at the end of the verse, i typically attach lyrics to a voice and put the lyrics for the lower part under the bar and those for the upper voice above the bar, (while still on the same verse). Is this feature likely to be in the first release? Hope this makes sense.

@Fraser: You can do that: either use Shift+up arrow to move the input position to above the staff rather than below and type the lyrics there, or type the lyrics as another line under the staff, then move them up by right-clicking one of them, and choosing Lyrics > Placement > Above from the context menu, as shown in the little gif animation.

Sorry daniel, obviously not clear in my question, say i have two voices, a sop and alto part in the same bar, can i associate different lyrics with the alto below to the sop above? For example in parts, they may have different rhythmic structures. Or do the lyrics just follow a single melody in a bar as in the example?

@Fraser: Yes, lyrics follow the rhythm of whichever voice you specify, i.e. by selecting a note in that voice at the point at which you want to start inputting lyrics.

Can frames overlap on a page? Or are they required to be disjoint?

Are you hoping to add layer support and blend modes eventually? The potential for graphic scores is very interesting.

@Ian: Frames can indeed overlap if you want or need them to. I’m not sure about a more generalised layers mechanism; beyond having control over the z-order of items drawn within a music frame, it’s not something we’ve given a lot of thought to as yet.

Great to hear that text frames can overlap music frames. Can you control the background of text frames – e.g. white or transparent?

@Ian: No, at present, all frames have transparent backgrounds. I expect this is something we could add in a future version.

Looking good! Two questions…

1) Will we be able to search and replace lyrics text?

2) If you choose a new line for an entered lyric, swapping would mess up the order of other verses; can the other lines simply be moved up or down to accommodate the change? For instance, if I decide to make lyric line 4 the new line 2, with swapping I end up with 1, 4, 3, 2. I’d have initially thought that most people would expect to end up with 1, 4, 2, 3.

@Iain: We don’t have any kind of search and replace at the moment, but that would definitely be a good feature for us to add (we probably won’t get it in before the first release, I’m afraid). I’ll have a think about your comment about the line swapping behaviour.

I’ve been following your blog for some time, eagerly awaiting this subject.

I’m a typography obsessive as well as a musician/teacher. I love InDesign because of the level of detail and control it offers, but setting teaching materials and books with musical examples is painfully tedious. I love the idea of an application that could handle everything, and this leaves me hungry for more details on the general type-setting capabilities you have planned. Just being able to have access to OpenType options would be a welcome start, but I’d guess you’ve got much more ambitious plans than that.

Thanks for so kindly giving us a peek at the work in progress, and all the time and work you’ve spent keeping this blog updated for us. Can’t wait to see it released!

@James: The level of typographical control provided in Dorico 1.0 will not be even close to the richness provided by current versions InDesign, I’m afraid, but that is absolutely the direction we would like to move towards as the application matures: the long-term goal is that you should not need InDesign for production of inners, even for complex publications. But I stress that this is the long-term goal and we will not be there in our first version. Hopefully it gives you a sense of our level of ambition for Dorico, though.

The UI Font looks promising. Is that Source Sans Pro?

@Shiki: Yes, it’s Source Sans Pro.

Bravo! 🙂

Great, I’ll definetly test-drive Dorico. I’m holding off Sibelius upgrade (I’m still on v7) because there hasn’t been much improvement in the “how the parts look” department. Positioning of chord symbols is simply not right, rehearsal marks can be all over the place if there’s a chord symbol or a high note in its way. Lots of small things that end up in endless hours of editing parts. IMHO one should not spend 50% of the time writing and the other 50% editing score and parts for them to look semi-decent. Dorico seems to be on the right path, you guys are much more anal about the little things than I am and that’s great.

Great stuff, as usual!

I wonder if Dorico’s page layout features make it easy to start on a left-hand side page instead of the usual right-hand side? In my current setup I have to resort to clumsy hacks to achieve this.

The use case is that many of my parts fit on two pages, and I print them on two sheets of paper to avoid page turns. If the software thinks the first page will be on the right-hand side, it can insert a “V.S.” where it doesn’t belong. And in any case, it will optimize for the wrong thing. Sometimes my music would otherwise fit on 2 pages, but it doesn’t since the program is trying to optimize the location of a nonexistent page turn between the first and second page.

@Veli: Dorico doesn’t allow you to do things like consider the first page a verso but still number it as 1, because… well, because that’s horrible and it offends us. But it certainly allows you to make the first page a verso, provided you are happy for it to be correctly numbered!

At the moment, Dorico doesn’t consider page turns when casting off. We certainly hope to offer options for this in future, but when we do, you will be able to easily control whether or not it should consider recto pages only when looking for page breaks.

Text: brilliant news on text boxes, paragraph style etc,. A major, major plus for me. Are you thinking in terms of basic text options – i.e. line height, alignment, indenting, bullet points ?

@David: I’m not sure exactly what kinds of typographical control will be included in the very first version, but over time we do anticipate adding those kinds of text features, yes.

Thanks Daniel – appreciated.

As usual, I’m as happy as the proverbial Larry with the way Dorico is going, with no reservations and no suggestions—although I daresay I’ll feel like putting in my two-bobs’ worth from time to time once I start using it.

I particularly like the approach to spacing of lyrics—in Sibelius 7.1.3 I find it necessary to intervene more often and more extensively than I would like, and given that most of my music has a vocal component—song, canzonet, cantata, Singspiel, opera—it is a matter of central importance to me.

Oh! Apparently I lied—I do have a question/request/suggestion.

At present, it is my habit to insert a single percussion line in Singspiel or opera scores to which I attach stage directions (SDs), boxed, usually hiding the staff line.

I like to think that in Dorico one could insert a ‘blank staff’ for SDs, with its ‘Instrument name’, the ‘staff’ appearing only as required, like any other vocal or instrumental staff, and occupying only as much vertical space as necessary.

Feasible, Daniel?

@Ralph: We don’t have the capability of creating staves with no lines at the moment, and I’m not sure that would be the way we would try to accomplish inserting stage directions like that in any case. I’ll have to think about it a bit, and I’ll let you know.

Thanks, Daniel,

There’s no rush—next such job will be in about December, and I’m sure I’ll be able to make do, even if you are still cogitating.

If it’s of any interest, I usually put stage directions above the top vocal line.

I’m very pleased to see all of the lyric improvements!

As a choral singer, I’ve become unhappy with Sib’s lyric spacing–I’ve witnessed/made lots of reading mistakes where bad rhythmic spacing due to lyrics contributed to misreading. Basically wasted rehearsal time due to non-attention by the typesetter (often a composer (understandably) using the software’s default output).

I currently use a two-step process in Sib7: (A) I initially (esp. when composing, but also when transcribing) let Sib space the lyrics and adjust the note spacing. This gives me a reasonable starting point for system breaks that will let the words and music fit. (B) I then have to lock the format, then change the music spacing to ignore the lyrics (so music is spaced solely based on rhythmic content), then I manually fix up all of the colliding lyrics. Occasionally, I also have to adjust system breaks, but mostly I’m changing the horizontal position of lyrics like you describe Dorico will do for me. (Yay!) I also frequently have to tweak the horizontal rhythmic spacing, but I can do a much more subtle job than Sib does, except when Sib does the “jumpy” spacing thing, in which case I do as well as I can without wasting tons of time.

It’s great to hear such care given to lyrics… I’d been waiting for Sib to get around to these kinds of improvements, and they’re finally here! This will save me a lot of time setting music. But equally important, it will really improve the default output from more naive users.

(BTW, I’m also really glad to hear that by default hyphen will always show!)

Tremendous stuff, simply tremendous. I can’t wait to get my hands on this software. So many of the vexing problems that have plagued me with other notation programs are being brilliantly and elegantly addressed here. And your UI looks outstanding.

Hi Daniel,

Layout & lyrics, with overrides of any kind… fantastic!

You guys are really doing it right. :-))

Looking forward!

Robert

Wow Dorico sounds amazing! I can’t wait!

Any chance you might implement an “articulation styles” feature to allow slurring/dotting/accenting to be applied as a style like a paragraph style in word? Tedious to me is updating articulations in one part and then laboriously updating all other parts anytime I want a change to several parts.

Additionally, a “master passage” feature allowing whole sections of music to be used anywhere, then updated in a master would also be a great time saver to me. Almost like a master page, but instead a master passage that could be updated throughout the score…with the ability of course to have multiple master passages as needed…

Great work Daniel!

Mike

@Mike: Slurs and dynamics (and indeed lyrics) can be shared between different instruments, but articulations can’t. Hopefully we’ll be able, in due course, to make it possible to copy and paste articulations independently from their notes. As for your idea of “master passages”, we have some underlying support for this kind of thing built-in, but I’m afraid it’s not going to be included in the first version: something for down the line.

In many of my vocal and choral scores I have passages that are almost recitative like, in a senza misura bar, under which there is often a sustained chord in (say) the strings. I usually use a breve notation to indicate it should be sustained, but if the chord or note needs to tie over to the next measured bar I have a problem getting the ties to behave themselves using Sibelius. Will Dorico make this easier?

@Derek: Insofar as Dorico will make it very easy to change the length of existing notes, and it also makes it easy to write senza misura passages, I would hope that you will find this kind of thing easier to handle in Dorico than in other programs.

Hi Daniel,

everything is really looking great! Very much looking forward to use your new software! We sometimes use fold-out pages for page turning reasons. Because these pages have to be cut off a little, they have a slightly different (smaller) layout. At the moment we produce these publications using Sibelius and InDesign. I would appreciate, if this would be possible in Dorico too. As I understand your Diary, this will be possible in Dorico. Will it be possible, to adjust this for the fold-out pages in one go or will it be possible to copy the layout?

@Heiko: Dorico doesn’t support fold-out pages per se, but it does allow you to create page number changes at will so that you can insert e.g. 5a, 5b, 5c for fold-out pages following page 5, and you can also set the size of the frames for these pages differently; however, the page size of all of the pages within a single layout must be the same (it’s specified once in Layout Options for each layout).

Hi Daniel, I understand that Dorico will not support chord symbols in its first iteration, but in my case (as well as many arrangers) I use the traditional forms of chord writing i.e. Cmaj7, Emin6, Bb7, etc. So if the Dorico supports any kind of text, then can I assume I can still write chords like the above example? Is the issue simply flats and sharps?

Thank you!

@Claude: You should be able to write sharps and flats in text simply by changing to Bravura Text (or another suitable font containing such symbols) within a run of text.

I cannot wait until the launch of Dorico. It’s the reason I never upgraded to Sibelius 8, because I did not want to shell out money too many times. It would be a useless upgrade when I already know of something better on the horizon!

Anyway, the real reason I am writing this is because I am wondering how many computers you will be able to install Dorico on. I use multiple machines, and some of them run multiple operating systems, and I did not know if I will need to purchase multiple licenses or not to be able to run this software on all of them.

I cannot wait until the release!

Thank you!

@Peter: You will be able to install and activate the software on one computer using the default Soft-eLicenser, but we will also supply a USB-eLicenser, onto which you can transfer your license in order to then run the software on up to three of your computers, by plugging the USB-eLicenser into the machine you want to use at that time. See here for more information.

I often include word-by-word translations of foreign text so that vocalists know exactly what they are saying. I usually do this as a second (or third) verse. That way the translation moves in sync with the notes (and foreign words) should the music or layout be changed. Unfortunately, this approach can create issues with music and lyric spacing as the program attempts to allow for “proper” spacing of the translation line when that is neither necessary nor desirable. I realize this likely won’t be included in the initial release, but might there be a way to indicate that a given line of “lyrics” should not be considered music and not affect the spacing of notes and other lyric lines? I’m open to other approaches for translation lines, but I can’t think of what they might be.

Great work! I’m excited to see Dorico when the first release is ready.

@Bruce: Certainly at the moment there’s no way of designating a particular line of lyrics to discount them from rhythmic spacing, but this is something we could consider for the future.

We absolutely love the lyrics features, but do not need all the other bells& whistles. Will there be a more pocket-friendly version like Finale PrintMusic or Finale SongWriter?

Thanks

@vovilibrary: Yes, we expect that at some point in the future we will broaden the Dorico product line with lower-cost, reduced feature set versions, just as is already the case for the Cubase product line, but we are not planning to release any cut-down versions in the near future, I’m afraid.

This looks great! Will the master pages be able to handle things like 4-handed piano music where you need every other part on every other page up to the same bar numbers?

@Erik: Yes, absolutely. All you need to do to set this up is unlink the frames on the left- and right-hand pages of the master page definition, so that left- and right-hand pages have independent chains of frames, then use the Player filter for the left-and page such that only the Secondo player is included, and likewise include only the Primo player on the right-hand page, and you’re done. If you create system breaks on either the left- or right-hand page, it will appear in the same place on the opposite page, so it’s very easy to produce a four-hands piano layout quicker than in any other program (to my knowledge).

Wonderful work Daniel. Can’t wait to get my fingers on Dorico.

Will Dorico be able to handle alternate language lyrics? For example, given a piece that is written in French, there might be an English translation of the lyrics given below it. Often times, that would mean changing the rhythms or adding/subtracting a couple notes here or there. Sometimes those additional notes would be smaller notes stemmed down. Will there be an easy way to do that in Dorico than the competitors?

I’m extremely excited about Dorico, by the way! I love the development diaries and how they offer a glimpse into the technical details of the workings! Thanks to all of you guys for your work

@James: It’s certainly very easy to create additional voices as needed with opposing stems, including direct control over whether or not those new voices should be padded with rests or just start and stop with the notes you need. It will also be easy to create lyrics attached to those voices. The only thing that is not possible as things stand today is to make one line of lyrics e.g. italic and another not (chorus lyrics are automatically italicised, but that’s not quite the same thing, of course). I’ll have a think about how this might be achieved.

Congratulations, you are doing a great job. I have a question: Is Dorico going to be available in Spanish? Because it would make Dorico easier to use for me and other people who don’t speak english very fluenty. Thank you, Dorico looks really interesting.

@Alan: Yes, Dorico will be available in Spanish (and French, Italian, Japanese, Brazilian Portuguese, Chinese, Japanese, and Russian).

And of course in Finnish, I assume. 😉 😉 😉 The country of Sibelius – and mine.

Turkish? 🙁

Turkish is, of course, the main language of Dorico. Others like English and German follow… 😉

Shame on you. 🙁 I am serious.

So am I. 🙂 🙂 🙂

It makes me happy to read the terms “responsive design” and “constraints” because being a web designer (besides being a professional musician) I’m currently switching to a new UI design/vector illustration application called Affinity Designer (which is an alternative to Adobe Illustrator – and developed in Nottingham, by the way) which is also under active development, and where UI concepts much similar to yours have been or are being implemented (e. g. different work modes for design, export etc., and also constraints).

I’m currently working with Finale but am eager to try Dorico and much looking forward to the workflow which seems somewhat similar to Affinity Designer.

As someone working with a lot of lyrics these days (more lyrics than music it seems!) I have a very broad appreciation of the problems of a successful setting. I am currently working with quite a tightly optimised format and the one saving grace of Finale and Sibelius is that there are means to “switch off” lyric spacing thereby allowing the note spacing to dominate. There may be improvements to the way Dorico handles syllables hyphenation and words but will we be able to use the same technique and switch off lyric spacing when there is just no way to achieve a good note spacing with lyric spacing active? And, as rare as this may seem, will it be possible to decrease the tracking/kerning or even glyph width in especially difficult areas?

@Stephen: At present in Dorico there’s no way to prevent lyrics from being taken into consideration when performing rhythmic spacing. I’m hopeful that you will find the need for this much less often in Dorico as it does a smarter job of spacing lyrics. You will eventually of course be able to adjust the rhythmic spacing and the position of the lyrics directly to resolve any local issues that might occur. At the moment, we don’t have detailed text and typography controls for things like kerning and character scaling, but I expect that these will all come in due course.

Please see that you allow Dorico to import all of my Sibelius files – at least the ones written with versions through Sibelius 6. Thanks, Daniel.

@Jack: I’m afraid Dorico will not be able to import Sibelius files directly. Please see the FAQ for more details.

Please SEE… that ALL… MY… files…

Wow! 😉 Never before have I seen anything that selfish. 😉

Dear Daniel,

I don’t know if this has already been asked, but will there be a variety of music fonts to choose from (such as a Jazz font)? Hope to hear from you soon!

Sincerely,

Paul

@Paul: Initially Dorico will come with just a single music font, Bravura, but it will be compatible with all SMuFL-compliant fonts. We are working on our own handwritten-style font, which will unfortunately not be ready in time for the first release, but hopefully some third-party font developers will answer your prayers with a variety of other fonts as well before too long.

Hi Daniel,

Thanks for your detailed sharing. Appreciate.

I must say I was sure to purchase the first version of Dorice, but was disappointed to find out the high cost for the cross grade price. 300$ for first version which doesn’t include Chords and guitar tabs/fret board is really a lot.

So I decided not to go for it.

But there is one thing that might influence my decision.

As a Sibelius user who usually write piano music (Treble + Bass Clefs),

Does Dorico use better intelligence (in terms of less manual fixing headache) to intuitive analyse a piano played midi with both hands (melodic + harmony) into score devided between Treble/Bass Clefs?

also better understanding the rhythmic patterns played (something that can be more readable) than the strange sibelius interpretation of what I played?

I spend hours fixing the notations after being freely played on my midi piano.

Sorry, meant Dorico (it was type in the first line)

@Yaron: The first release of Dorico does not include real-time recording and transcription from a MIDI keyboard (though you will be able to use step-time input with your keyboard), so I’m afraid it doesn’t have a good solution for your transcription problem just yet.

I wonder if Dorico will suitable for contemporary music notation…

@Richard: I think Dorico will be suitable for a good many kinds of contemporary music notation, with its excellent support for tuplets, microtonality, complex meter (including open meter), and so on. However, in its first version it will not be equipped with a lot of purely graphical flexibility, e.g. the ability to use custom lines, graphics and so on in an integrated fashion (though you can achieve a lot with the graphics frame functionality, since you can import SVGs and then resize them freely and position them where they need to go). I would say that Dorico makes a solid start in this area but we will be able to greatly expand its capability in future.

“I would say that Dorico makes a solid start in this area but we will be able to greatly expand its capability in future”… Solid start for the same or higher money amount like Finale or Sibelius, which are very flexible in graphic elements??? I think that many contemporary composers who use Sibelius or Finale will “remain from the side”…

@Richard: I think you have to have realistic expectations. Sibelius and Finale are mature applications that have had, between them, about half a century of development work, literally hundreds of man-years. You cannot reasonably expect Dorico to have all of the features that Finale and Sibelius have accrued over the course of all of these years in its first version – or, at least, if you do expect that, you will be disappointed. I hope that there will nevertheless be many things to interest you in the first version of Dorico, and that the program will only become more interesting still to you as it matures.

From notaion software (I am a professional composer) I expect professional functionality… If it costs more than Finale or Sibelius, than the software functions have to meet the expectations of professionals and not amateurs, according to the price of other professional software

@Richard: One of the main reasons the first version of Dorico doesn’t have every feature that Finale and Sibelius have, aside from the hopefully obvious fact that Finale and Sibelius have been in development for decades now, is that we are aiming to complete every feature we implement to the standard required by professional users. It takes time — a lot of time — to develop high-quality, capable software. In the end, nobody is going to force you to buy Dorico. If you don’t think it represents good value for money for you, then simply don’t buy it. But if you are serious about making music notation on your computer, then I think you owe it to yourself to give Dorico an impartial look.

One more thing. Let Dorico easy hide any element of score and create own symbols and lines to achive modern contemporary layout. With these functions Dorico will the best score notiation software

Dear Daniel,

What about the trill ends (doesn’t works in Sibelius: http://www.sibelius.com/helpcenter/article.php?id=336&languageid=1&searchid=3044805) that’s not a solution. It worked fine in Turandot, but doesn’t exists anymore.

@Czentnár: Dorico does have good support for positioning grace notes before the barline. All you have to do is add the grace notes at the rhythmic position following the barline, then select the rightmost grace note that you want to appear to the left of the barline, and switch on the relevant property. This is stable on future editing, spaced properly, and so on.

Daniel

A fussy question about lyrics. I sometimes prepare performing scores of liturgical music from 15/16thC choirbooks, in which the scribes often adopt an approximate approach to lyric placement and completeness. Normal editorial practice is to type text that is in the source in Roman type. Text added to fill gaps or show repetitions not shown in the source are typed in italic type, so you have both Roman and italic text in the same line. Can Dorico do this?

Michael

@Michael: It’s actually a little tricky to change between Roman and italic text for individual lyrics or syllables within the same line, but we could potentially add a property to allow this in future. I’ll make a note of it.

Daniel

Thank you. Of course, the ability to switch between Roman and italic text in the same line is important also e.g. for macaronic texts (looking forward to Christmas, such as In dulci jubilo, There is no rose) so it’s definitely needed. Sibelius has been able to do this at least since Sib5, if not earlier.

Hi Daniel,

Thanks for the update. A feature that I would really like to see deals with tied notes and second endings, and the continuation of a melisma to that ending. For example, if there is a word that is sung starting in the measure immediately preceding the first ending, in my current software, I can continue the text line/melisma indication to the first ending quite easily (it is just treated as the subsequent measure). However, when that held note/word needs to continue to the second ending, I have to create a text line/melisma indication from scratch, and I have to create slurs and ties from scratch in order to make it look as though the notes are naturally tied to the notes in the second ending. It’s a major pain and there must be a way to streamline this process.

Do you have any plans for a workaround for this in Dorico?

Thanks for your work!

@Jake: The first version of Dorico will not, I’m afraid, support first and second endings at all, but when we do, we do intend to try to come up with a good solution to the issue of things that continue into the endings.

Dorico is only for Windows 10!!! ??? (not available for earlier 64 bit version… like Win 8 or 7) in my opinion very stupid idea… good luck Steinberg

@Richard: Dorico is only officially supported on Windows 10 64-bit, but we have been running Dorico on Windows 7 64-bit, and on Windows 8.1 64-bit, and it runs fine on those operating systems. The issue is simply that we have limited support and testing resources, and we cannot qualify the software fully on every possible version of the operating system. So use Dorico on Windows 7 or Windows 8.1 at your own risk, but I do not anticipate that you will encounter any problems.

but if I will have problems? Do you return money??? You don’t provide demo version…

@Richard: A fully-functional 30-day trial version will be available before the end of November, so you can try Dorico before you buy. You just have to wait a few more weeks for the trial to be made available.