After the last instalment’s detailed discussion of beam grouping and sloping, today’s development update is going to focus on some of the issues around laying out a page of music, in particular working in the horizontal dimension, including casting off and justification.

From galley view towards page view

The first kind of view onto the musical score that we implemented in our new application was an infinitely-wide view that lays the music out in a single system. In other applications, this is called things like scroll view, continuous view, or even Panorama; we call it galley view. This is an allusion to the use of the term in print publishing, when the typesetter would produce an initial proof of a book, having laid out the metal type into galleys, the trays that hold the individual pieces of type.

Although galley proofs for books are still typically laid out on pages, those pages are normally not bound together, and indeed are often handed to the proof-reader in signatures (large sheets of paper with multiple pages printed on them, which will eventually be cut and folded to produce the correct sequence of pages when the book is imposed). The analogy is imperfect, since in our application galley view produces no pages at all, but it is the same in spirit: a proof-reader looking at a galley proof is normally looking for typesetting errors, rather than examining the final layout in detail (that later stage of proof-reading uses page proofs), and the purpose of galley view in our application is to allow you to focus on the musical content, rather than on the final system and page layout1.

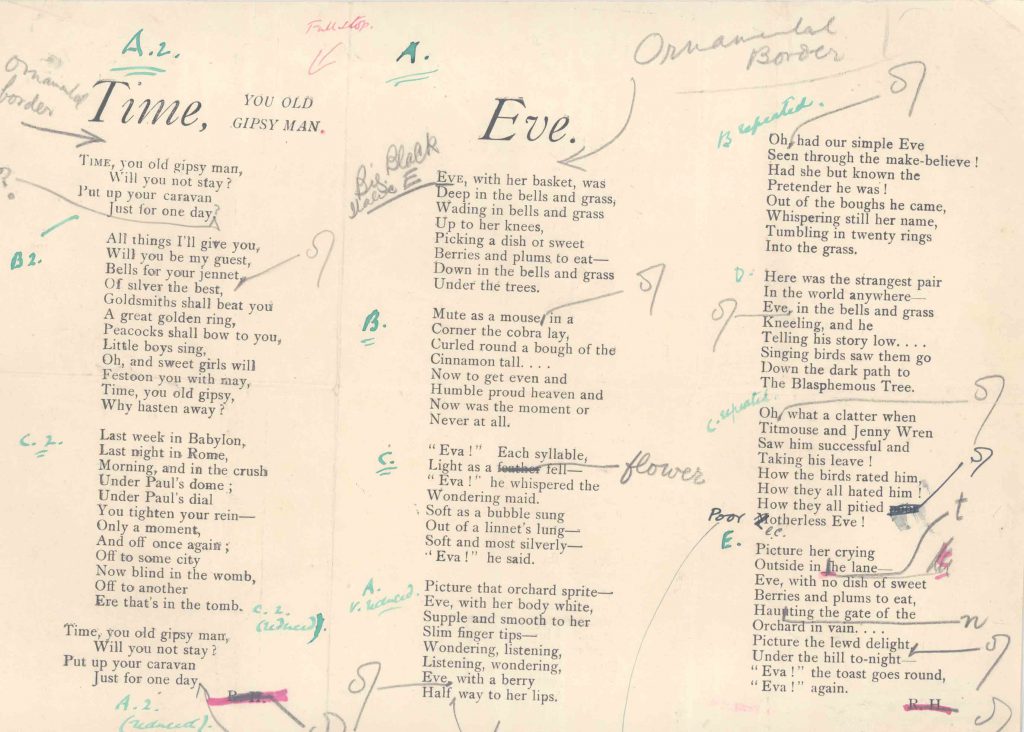

A galley proof of a poem by Ralph Hodgson. Image courtesy of the special collections at Bryn Mawr College Library.

Galley view has been implemented since the very first temporary drawing of the music that we achieved two summers ago. We later put in a very simple version of what we at the time rather optimistically called page view, where the music would be drawn on a single page of infinite height, with the music split into systems of four bars each, regardless of how wide or narrow each system ends up. The main purpose of this was to expose the sorts of issues that arise with notations that start on one system, and end on the next: ties, slurs, beams, octave lines, and so on, and so on. Each kind of notation needs special handling to ensure that it is laid out correctly on either side of the system break.

We also implemented a debug option that would force a new system at intervals of an arbitrary number of quarter note (crotchet) beats, even if that position did not correspond to a barline, i.e. in the middle of a bar: this helped to expose less common sorts of issues, such as what happens if you need a system break to occur in the middle of a tuplet, and so on. Because our application has built-in support for open time signatures, where bars can be of any length, it’s crucial that it can place a system break at any rhythmic position, so these kinds of simplistic options are important in forcing us to think about how to handle the different ways in which notations must be represented on either side of a system break.

Over the past few months, however, we’ve started to work incrementally on taking that very basic page view and moving it closer to an actual page-based view of the music. We have to date focused on the horizontal aspects of page layout: casting off music into systems, calculating the rhythmic space required by the music on each system, and then justifying the music into the available width, processes which are somewhat interdependent and which I will discuss in more detail below.

There are also, of course, the vertical aspects of page layout: setting the appropriate distances between staves within a system, determining how many systems can fit onto a page of a given height, and then justifying the music into the available height. Work in this area is just beginning in earnest.

Splitting up the process of laying out a page of music down into smaller, more discrete steps is in the spirit of the architecture of our application: we always break complex problems down into smaller, (hopefully) simpler ones, writing individual engines (which we call processors) to solve each problem in isolation, before chaining together them together to tackle the larger issue.

Rhythmic spacing

I’ve discussed our general approach to rhythmic spacing before, including the ability to kern adjacent columns, introducing additional space above and beyond the rhythmic space that should be allocated to each column only when necessary: for example, the presence of a group of accidentals on a chord will only require additional space to be allocated if they would otherwise collide with the previous note or chord; if they can tuck above or below the previous note or chord, then they will. In addition to the crucial benefit of ensuring that the rhythmic spacing is as consistent as possible, another important benefit of this approach is that our application can determine exactly the minimum amount of space to space the music with correct rhythmic proportions, and no collisions between items.

Casting off

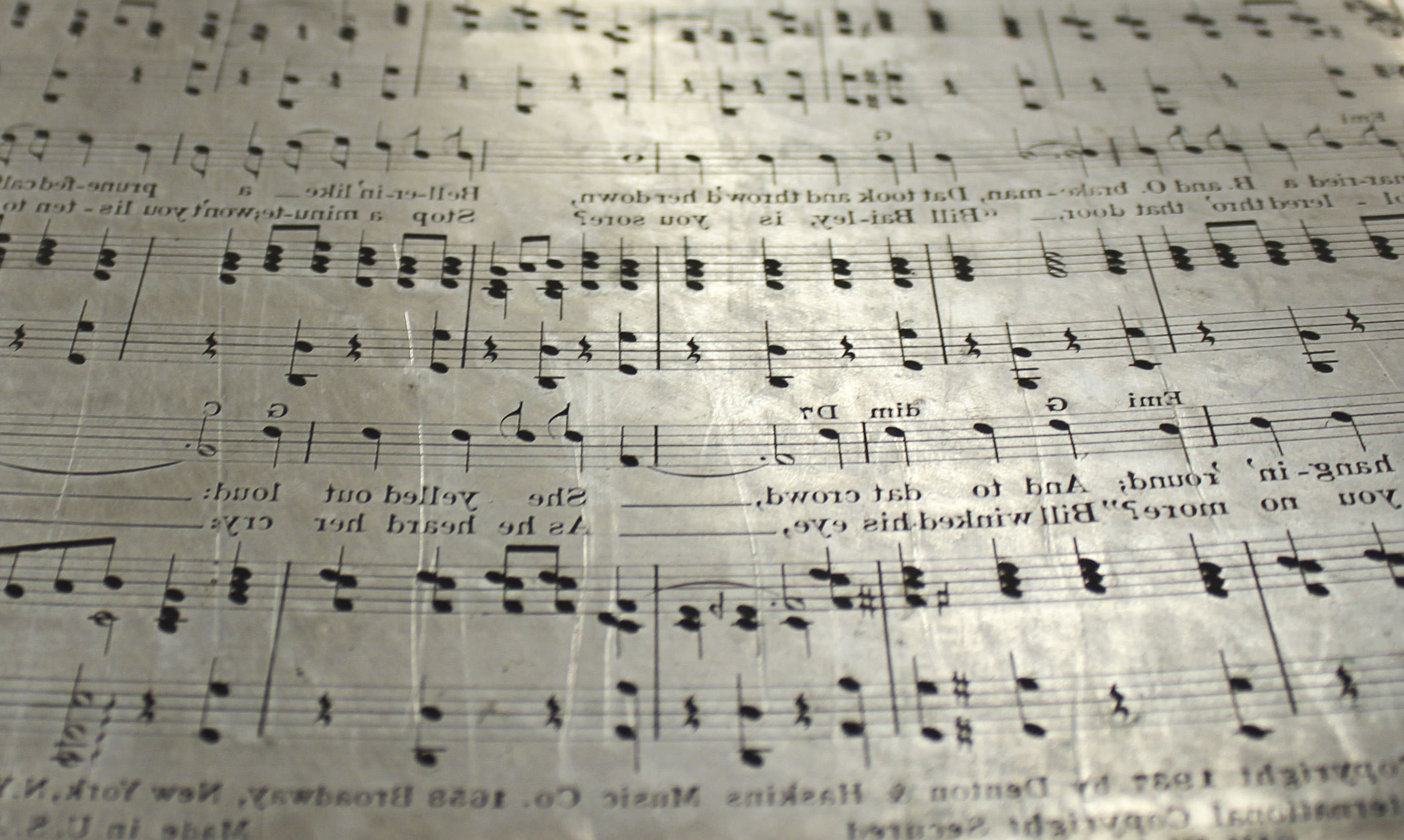

The knowledge of exactly how much space a given span of music requires is an input into the processor that determines the casting off of each system. Casting off is another term borrowed from print publishing, where it refers to the process of estimating the number of signatures required to typeset a given text. In music publishing, casting off is the process of determining how bars should be distributed within systems, and how systems should be distributed within pages, to produce a pleasing layout that uses the appropriate (not necessarily minimal) number of pages. Just as in print publishing, where complex considerations concerning widows (one or two lines at the start of a paragraph left at the end of one page) and orphans (a few words at the end of a paragraph spilling onto a new page), starting new chapters or sections on right-hand pages, ensuring that no two successive lines end with a hyphenated word, and so on, the process of casting off music is something that requires a good deal of skill.

Before engraving became computerised, casting off was normally the first step in preparing a piece: the engraver would mark up the manuscript or whatever source he was working from, and plan out how much music would appear on each system. He would do this even before working out the punctuation of the music2. Casting off is definitely more of an art than a science: engraver George McGuire, a recipient of many Paul Revere Awards (given out by the Music Publishers’ Association of the USA in recognition of excellence in music engraving), wrote:

“This is not an easy thing to do. Nor is it easy to describe how it is done. No one can tell you how to ride a bicycle, you learn by doing it – and falling off.”

Casting off, therefore, is one of the most difficult processes to ask a computer to perform, since it requires a high degree of judgement and discretion to do it well. However, there are aspects of casting off that a computer can perform much more efficiently than a human, and can arrive at a good result by way of a more deterministic method.

A human engraver, for example, must calculate the punctuation of the music by hand. He won’t have the time or inclination to do each system more than once, if at all possible, so based on his prior experience, he will make a number of quick decisions at the start of the process that will eliminate many possible solutions from the outset. He will make a judgement about the page size, the page margins, and the rastral (stave) size. These fundamental dimensions have an enormous impact on the punctuation; changing any one of these variables will dramatically alter the final layout of the music. To give a very simple example, using a larger rastral size will reduce the amount of rhythmic space (often measured in notehead widths, which are normally just a little more than one space wide, the space being the distance between two adjacent stave lines), so less music will fit onto the system.

A human engraver must also very carefully consider the vertical dimension at the outset: he must determine where the distance between staves must be increased to accommodate very high or low notes, or extra playing techniques, and so on. Once the staves are marked on the plate, or stenciled onto the page, it is very costly to go back and change his mind.

The computer, on the other hand, can perform the calculations required to punctuate the music in the blink of an eye. It can cope with changes to any of the vital statistics – page size, margins, stave size – at any point in the process. And, of course, the cost of making a change to the casting off is practically zero, because everything can be redone in an instant if the engraver changes his mind, if more music is added, or if the existing music is edited.

The computer can, to some degree, compensate for its lack of human judgement and discretion through its ability to evaluate combinations of possibilities thousands of times more quickly than a person can. When the computer performs casting off, unlike the human engraver, it starts with the punctuation: this gives an objective measure of the amount of space required to typset a span of music while producing appropriately proportioned spacing for the rhythm without any items colliding graphically. The computer also knows the width into which the music must be flowed: this will typically be the page width, minus the page margins, minus the width occupied by the staff labels, brackets or braces, and initial clef and, if appropriate, key and time signatures at the start of the system.

Most scoring programs seem to use a variant a kind of “greedy” approach to casting off: each system is simply filled up as much as possible, working from the start of the score to the end, which means that they might be left with a final system that is almost empty, and they deal with this remainder in different ways. Product A3, for example, appears to distribute the remainder over the last two systems. Product B chooses not to deal with the remainder at all, and will happily allow the last system to contain only one bar (though, in its defence, it provides very efficient tools to move bars between systems that help the user to exercise his or her judgement over casting off very quickly.)

Product C, according to its documentation, tries to produce an optimal result for casting off all systems. Since real-time performance is not a requirement for an application that produces output compiled from a text-based input format, the trade-off between requiring more computation to calculate the result and the speed of arriving at that result is a good one. For real-time, interactive applications, however, a compromise is needed in order to balance the quality of the result against the time taken to compute it. One design goal for our application in particular is to always do only the minimal amount of recalculation to respond to an edit, to make the performance of the application as high as possible.

Because there’s no one perfect solution to casting off any given score, the various scoring applications have all taken different approaches to solving the problem. Each approach has benefits and compromises, and it’s instructive to compare the results of each against our application, and against the results achieved by an expert human engraver.

Let’s look at an example: we’ll start with the Edition Peters engraving of Fugue 16 from Book 1 of Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier4, the G minor BWV 861. The engraver has successfully cast off the 34 bars of music onto two pages, with a very consistent layout: of 11 systems, all but one have three bars, with the fourth system having four. The engraving becomes tighter as the rhythmic complexity grows with the introduction of the third and fourth voices, but it is always very clear.

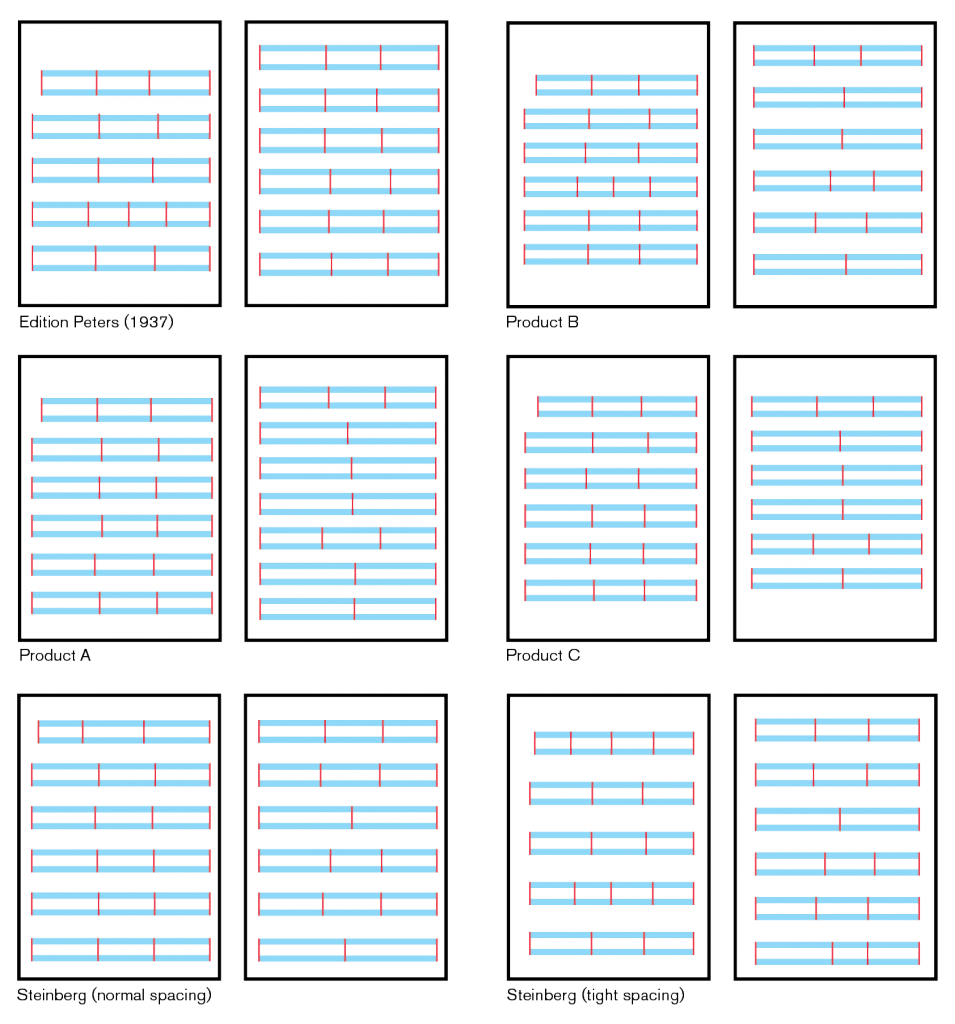

Here is a comparison of the default results produced by Product A, Product B, Product C, and our own application:5

A comparison of the casting off of BWV 861 by four scoring applications, using the Edition Peters engraving (1937) as the point of comparison.

All of the applications produce 12 systems by default, rather than 11, with the result that there are a number of systems that only contain two bars, rather than three. None of the applications produce a result as consistent as the original engraving by default.

The result from our own application is based on using its default rhythmic spacing, which is wider than the Edition Peters engraving, and comparable to the default rhythmic spacing of the other applications. However, because of the sophisticated rhythmic spacing algorithm we have implemented, it’s possible to make the spacing more narrow by changing a single value, which produces spacing much closer to the original engraving, and also produces a solution with 11 systems rather than 12 (though our application bites off four bars for the first system as well as the fourth, so it still produces one system of two bars on the second page). Here is an image showing bars 29–31, with the original engraving above and our application’s result below:

Bars 29–31 of BWV 861; above, an extract from the Edition Peters engraving, 1937; below, an extract from our in-development application.

(There has been no editing of the appearance or positioning of any of the elements in the image from our application, by the way: these are the default results when opening a MusicXML file with no positioning information included.)

Justification

The final element of the horizontal aspect of page layout is justification, another term borrowed from the related world of text typography and publishing. Justified text is where the spaces between words (and, sometimes, the spaces between individual letters) are increased to align both the left- and right-hand ends of the text with the surrounding lines, the page margins, or the gutter between columns.

Music is almost always justified: the stave starts at the left-hand page margin, and ends at the right-hand page margin. The process of spreading out the music to close the gap between the required width (providing adequate rhythmic space while avoiding collisions) and the available width (i.e. the width of the stave, minus the width of the items that appear on every system) is what we call justification.

In the days of hand engraving, the application of justification was another area where human judgement had to be carefully applied. Imagine that your available space, once you have subtracted the page margins and the musical preamble at the beginning of the system, is 120 spaces. Having completed the casting off, the required space for the bars to be included in this system is 111.5 spaces. Now, across the width of the whole system, a surplus 8.5 spaces must be distributed in a way that does not produce distortion.

The strategy that the engraver would employ to distribute the surplus space varies according to the number and duration of notes on the system. One strategy, for example, would be to identify the longest notes, and to allocate the surplus space equally only to the longest notes; if this doesn’t work out nicely, you might allocate it in smaller parcels to all of the notes that have the most frequently used duration; and so on. The one thing that a human engraver would find troublesome to achieve would be to distribute the surplus space absolutely evenly between all of the columns in the system, because this would typically mean adding a tiny amount of space very precisely to every column.

Of course, for a computer, applying a tiny fraction of a space to each column in a system is a simple bit of arithmetic, and will give overall more consistent results, particularly in the case of complex cross-rhythms and tuplets. This is an example of where a computer’s precision actually improves upon the more rough and ready approach taken by a human engraver. The computer can also more easily introduce small adjustments designed to produce a more optically pleasing result (for example, to ensure that the graphical distance between successive notes with opposing stem directions appears more equal to the eye).

By way of illustration, here are the same three bars of BWV 861 shown above, first drawn with justification disabled, and then drawn with justification enabled:

Notice how, even in the unjustified case, no elements are colliding: look, for example, at the left-hand F#2 on the third beat of bar 31, and notice how it is tucked underneath the preceding E3. There is no distortion of the rhythmic spacing caused by the presence of the accidental on the F#2, as is the case with other scoring applications. Even in the justified case, the accidental still tucks nicely underneath the preceding note, though the justification adds a little extra space between these two columns, so the accidental is not too tight on the previous note’s stem.

Vertical spacing

Of course, spacing the music according to its rhythmic durations, casting it off into systems, and then justifying the leftover width only addresses the horizontal dimension of page layout. In order to produce a complete page of music, the vertical dimension must be considered too: determining not only the optimal spacing between staves within a system, but also distributing the systems within the available height of the page as well.

The other important factors are the stave size, and the page size. Our application makes it very simple to change the stave size: a default stave size is defined for each layout, and the staves belonging to an individual player can be set to a different size expressed as a percentage of the default size – though the use of more than two different stave sizes within the same system is very rare; for example, ossia staves are typically three-quarters the size of the default, and small staves used to cue in a soloist’s part for the pianist in, say, a violin sonata are similarly sized. In some works for large ensembles, the number of staves may change from one movement to the next, or even sometimes within the same movement. To ensure an optimal layout throughout the whole score, it may therefore be necessary to change the default stave size, which can be done easily at any system break.

There is a great deal that could be written about the vertical aspects of page layout, but further discussion will have to wait for another instalment of this diary.

That’s all, folks

Of course a great deal of other work is going on. Our colleagues in Hamburg are continuing to work on extracting the audio engine from Cubase so that it can be integrated with our application; we continue to improve the input and editing workflows; we continue to iterate on the visual design of the application; we are starting to build the infrastructure that will make it easy to change the appearance of any notated element in your project; we are using the metadata defined in Bravura for fine adjustments to things like how stems attach to noteheads; we have beautiful slurs; and more besides. But all of this will have to wait for another time.

In the meantime, from all of us in London, thank you for taking an interest in the development of our application. If you have any questions or comments, please don’t be shy: leave a comment using the form below, or feel free to contact me directly.

- “Galley view” also happens to be the name given to this kind of view in MOTU’s venerable Mac OS scoring program, Composer’s Mosaic. ↩

- Punctuation is described in part 9 of this development diary, but briefly: it’s the process of determining what the columns to be spaced are, by creating a new column for each note onset across all of the staves in the system, and assigning the rhythmic value of the shortest sounding note across all systems to that column, to determine the allocation of rhythmic space to columns. ↩

- Product A and Product B are the two leading commercial, proprietary scoring applications; Product C is an open-source music engraving package that uses a text-based input format. ↩

- See pages 17 and 18 in this PDF, available from ISMLP (#69275). ↩

- A note on the methodology used in this comparison. A MusicXML file, containing no page and system formatting data, was opened in Product A and Product B, and the page size, page margins, stave size, and stave spacing parameters were changed to try to achieve the same density of systems per page and available horizontal space as the Edition Peters engraving. No changes were made to the default rhythmic spacing options. For Product C, the same MusicXML file was converted to the appropriate text input file using a tool supplied with Product C, and the resulting input file was lightly modified to set the page size, stave size, and page margins to match the Edition Peters engraving; neither the default stave spacing nor the default spacing was modified. For our own application, the same MusicXML file was opened, and the only adjustment made was to the stave size (at present, the page width is hardcoded, so it is instead necessary to adjust the stave size such that it is in proportion with the hardcoded width). ↩

Keep on keeping on, Daniel! I have money ready to go when you are.

Ah! After Avid released Sibelius 7.6 and rounded it up to 8, I was in need of another bit of good news from the notation world, and here you are! I can’t wait until the discussion turns to user interface concepts, as that is my great area of concern and hope for your new application.

Your approach and communication with all of us in the note mines is greatly appreciated, Daniel… Fight the good fight!

I keep wanting to ask when it’s going to be ready, but dare not. However, from the examples above, it seems it’s well on the way. Very exciting!

Glorious

As always, a welcome, fascinating update. I’ll be interested to see the effect of adding lyrics into the mix as their own spacing and positioning beneath the notes throw a wrench into solely musical spacing considerations. Keep up the good work!

Hear-Hear!

You are making us all excited with the possibilities with this new application Daniel !!!

It seems with your posts one may prognosticate that it is still a year or two out from introduction?

On another note I hope that this application will accept third party fonts to use also?

Wow! Its great to see that you’re taking such a meticulous approach to the notation side of things, really bringing back the craft of engraving!

I know I shouldn’t ask, but I’m simply desperate to know: can you give us any indication of the applications release date? Do you think it will be less time than has already passed since you started working on the application? I’m sorry to pester, but my excitement (coupled with my frustration with Avid’s neglect of Sibelius) makes me anxious to know!

@S. May: I do think we are more than halfway towards the release of our first version, yes, but I can’t be any more specific than that. We’re going absolutely as fast as we can, but we are trying to maintain our commitment to high quality above all else.

> we are trying to maintain our commitment to high quality above all else.

As you should! Bravo to Steinberg for affording you all the time to do this! We’re cheering you on!

Thanks Daniel! Its great to know the future of notation software is in such expert and capable hands!

Kudos to you and your team, Daniel! I perceive you are taking great pains to avoid imitation of the code, UI, and terminology of Sibelius and Finale (for good reason), and are endowing the new application with a distinctly classical, and even literary, bent…Bravo! I’m guessing from your above estimate that your first release will occur in, roughly, 2019 or 2020 (?). I look forward to the time when those of us “From The Beginning of Time” Sibelians will have weathered the current dry spell of nil notational development, and shall welcome Steinberg’s offering with open arms.

@Flare: I expect that our first release will come much sooner than 2019 or 2020. That would put the development time for the first version at something like seven years, which would be stretching the patience of our colleagues in Hamburg beyond breaking point, I think! We will release something as soon as we have a critical mass of functionality at an acceptable level of quality. Our first release will not have every feature that the competing applications have, but those that it does have will be polished, and it will also have some features that the competing applications just don’t have…

>I expect that our first release will come much sooner than 2019 or 2020.

Wonderful! Can’t wait. We’re all saving our Euros for that moment.

“it will also have some features that the competing applications just don’t have…”

Ba ha… ba ha ha… BA HA HA HA HA HA HA HA!!!!!!!!!!!

Dan, you know how to excite! I’m literally getting goosebumps and tingles on the back of my neck. 🙂

Fantastic update, Daniel, thank you! It sounds like there will finally be a program to convince me to give up SCORE once and for all. 🙂 Wonderful examples of the tricky issues of casting off and justification.

Fantastic Daniel, sounds great. Good luck with everything.

You guys should talk to the NotePerformer folks. That’s a killer playback engine that would integrate well with a modern notation package (It’s only “good” when tied down to Sib, since it’s limited by the playback dictionary). NotePerformer is really wonderful, especially given it’s overall size of only 1GB.

Seconded, although I’m sure at this stage the playback engine is a minor concern, if even at all significant for an 1.0 release. Not that I wouldn’t be dying to see what they might come up with, but from Steinberg’s POV I can very plausibly imagine a fully functional score writer without any kind of polish for the playback for the initial product version. That way, they would be able to release earlier on and also have something worthwhile to offer for an 1.5 or 2.0 release later on.

Also, development seems pretty focused on notation issues right (as it should). Once the deadline rush comes on (as it nearly always does in the world of professional software engineering), they might well decide to just skip the headaches of a smart playback engine altogether in favor of a more focused development of the core features, to get back to the playback later on when everything is a bit less stressful.

That would be unfortunate. For a hack like me that uses notation software to compose, if there isn’t a fairly decent sounding playback engine available the software might as well not exist.

@Tyler: I don’t anticipate that NotePerformer will be included with our application, but we would definitely be open to working with Arne Wallander to allow him to produce a version of NotePerformer that works with our application as seamlessly as it does with Sibelius, if he is interested. We will include a library of sounds drawn from our existing products, which will play back using a built-in version of the HALion Sonic SE VST instrument. I hope you will find that it reaches the bar of “fairly decent sounding”, though when we surveyed our potential users about this issue a year ago, more than three quarters of respondents said that they had bought at least one third-party sound library or virtual instrument for use with their current scoring software, so I think in general it is more important for us to make it easy to use any third-party VI with our application than it is to ship any particular instrument or library in the box.

That is a very smart choice, no need to reinvent the wheel with what Steinberg has readily available; and everyone has their own preferences anyway. The Sibelius system with the sound world was a beautiful idea but in practice it is tedious to use third party VSTs with Sibelius, even with the soundsets created by Jon Loving. Keep it simple and stupid if that’s at all possible, and use the developing resources available at Steinberg’s Cubase team. Cheers! 🙂

I think this is a case where you might be able to innovate. I would argue, for instance, that for playback purposes VST is actually a *terrible* choice, and some alternative protocol that allows the VI to know much more about the score would enable vastly superior VI integration, by being able to plan out keyswitch triggers in advance, instead of for instance, with a group of stacatto notes trigger the staccato keyswitch before each note, then going back to normal mode, then retrigger stacatto.

(PS: The actual sound quality is actually less important, I’m much more interested in the playback of the “musical content” as a real performer would.

The gold standard in this department, was a little known bit of software called Igor Engraver. Despite just using general MIDI for playback it got so many things right – phrasing, tremolos (Long sustained woodwind tremolo? The first few notes would be a bit slower instead of it just being a consistent speed). Sadly, Igor was written in some sort of weird Lisp variant so it doesn’t install or run on anything newer than, if I recall, Windows 98.

I could not disagree more. A *composer* needs only a pen, no playback features at all. For composing, a good pen and good paper are needed, nothing more. That is what Daniel and the guys are correctly working hard on to provide us with which is really really great. This is exactly what I and many other composers have been waiting for for many many years. To say that a software might as well not exist if it does not have playback capabilities is strange, even impolite. Not that a playback engine would hurt, though.

Regarding playback, I have plenty of third-party sounds already. What matters to me for playback is that it can easily and effectively trigger those sounds.

I completely agree, Jonathan. I know what instruments and voices sound like; I use playback only to check my accuracy on pitches and rhythms. Furthermore I understand that in performance, players make interpretive choices that can never be reproduced in a playback system. I want clean notation software, and I want developers to concentrate on the fundamentals, not on frills.

You (me!) can’t argue with that!

+1. I’ve now taken to using NotePerformer for all full orchestra scores. Despite the fact that VSL bring higher quality samples, NP produces a much more musical end result than the SE version at any rate which is what normal mortals are able to run (which doesn’t mean that Vienna doesn’t have a place in smaller ensembles where the emphasis is more on individual timbre rather than musical ensemble).

For what it’s worth, I come strongly down on the side of Tyler and others who regard a good playback engine as an essential part of notation software. NotePerformer has this intelligence built in (at least to some degree) but if the notation software was able to make musical sense of conventional sample libraries, it would be a huge step forward. Not everyone is able to get complex works for full orchestra performed by live musicians for instance.

Another very interesting update, Daniel! The more time I spend engraving music, the more impressed I am at each one of these notation programs with everything they have to consider. Quite the challenging math problem! I hope everything continues to go very well for your team!

One thing, though, that you may or may not want to hear. I’m not sure I like how far apart the opposing voices are in Steinberg’s engraver in the BWV example you use (top staff, first bar, beats 1.5 and 2.5 between the 16th notes in voice one and the eighth notes in voice two). They seem so far apart that I had to second guess the rhythm of what I saw. Take that for what it’s worth, I guess. Onward to perfection!

@Abraham: Of course the gaps used by the software to tuck these voices are easily tweakable by the user. Many of these aspects are a matter of taste. These gaps look good to me, but if you prefer something different, it’s the work of a moment to adjust them.

I looked at the scores again Daniel, it’s beautiful, but there’s one thing you might want to change: in bar 29, F staff, the F# is a little too close to the Eb from the key signature, at least for my eyes; a little confusing. The Henle original layout is better. I’m not a piano player so feel free to ignore me. But since this is about alignment and justification, thought I would mention this. Cheers!

It’s not so bad to read (as a pianist). However, I agree the accidentals are a little too close. It may be helpful to position the key signature a little more to the left as well. But I’m guessing there will be parameters available to allow adjustment for both areas.

You’re right. There -must- be some sort of ‘left margin’ setting which guarantees a minimum space between the key sig and the first note on the staff. That would drive me nuts sight-reading.

The F natural in bar 30 is also bad. It almost looks like the ‘gap’ algorithm doesn’t provide the same minimal spacing with accidentals the way it does actual notes. IOW: that natural should -not- be kerned so tight. It should -always- have more space to the left.

Looks great, otherwise.

@Peter: We’ve certainly discussed how close you should allow an accidental on the first note on a system to get to the prevailing key signature drawn at the start of the system. At the moment, we treat that situation the same way as we treat the first note following a barline, where there is a certain default gap between the barline and the first note defined, and the accidental is allowed to encroach into that gap, provided it does not cause the accidental to collide with the barline, in which case the note and its associated accidental is moved to the right. We may want to make the first rhythmic position of the system special. All things are possible, given the will and the time!

Looks good!

Here’s to you all!

I whipped together a quick MusicXML file with this BWV 861 snippet, for those of us working on our own notation programs. Here is the file: http://red-bean.com/~adrian/soundslice/2015-06-29_steinberg_test.xml

Here’s how Soundslice renders it: https://www.soundslice.com/scores/29491/ It turned out better than I expected — and we even support fingerings, which I’m certain Daniel will cover in a subsequent post. 😉

Thanks for the great writeups, as always!

Adrian

Thank you for your contribution, I’ve tried it out as well…

Default score rendering in PriMus: http://cboensel.de/data/2015-06-29_steinberg_test.png

Slightly different XML-export of PriMus: http://cboensel.de/data/2015-06-29_steinberg_test_pri.xml

Very interesting, as always…

Speaking as one who started on Professional Composer (for PC – the first engraving software I heard of), then spent a decade or more on Finale with a brief detour through Nightingale, finally switching to Sibelius 6 years ago, I am very excited about your blogs.

Can’t wait!

LB

I began with Deluxe Music Construction set on a MacPlus in 1988. Amazing how far things have come – on the other hand, that was nearly 30 years ago 😉

Professional Composer (Mac), then Finale (starting in Beta) for me until switching to Sibelius in 2011. I’m ready to make another switch. Sooner than 2019 is good, 2016 or 17 would be great!

Any idea when this product will be released?

And thank you!

I searched the word “release” and got my answer, thanks.

“@S. May: I do think we are more than halfway towards the release of our first version, yes, but I can’t be any more specific than that.”

I love these updates, and please, take all the time you need. Keep up the good work!

Looks great! For me the big big question is whether I will be able to import my thousands of existing Sibelius 4 and Sibelius 6 files.

@Steve: You won’t be able to import Sibelius or Finale files directly, no (see the FAQ for more on why), but you will be able to import your existing projects by way of MusicXML.

I have two questions.

At the moment I create full scores on a page by page basis. This is partly an inherited instinct from the 35 years I spent writing scores by hand, and partly because with current software things can change radically if you leave the page layout and justification to the end of the process and I’m NOT a good proofreader.

Consequently, having finished all the movements in a multi movement work as separate files, I then concatenate them at the end in order to produce a printable full score with correct pagination, and rehearsal marks (I always force the first rehearsal mark of each movement to be 1) – I can’t use letters because my movements are too long and I’d be looking at AAA plus.

That is OK as far as it goes, but if any particular movement happens to use divisi strings on extra staves or introduces more or less instruments my current software (Sibelius) will not concatenate correctly, or often not at all, forcing me to introduce the extra staves in each and every movement.

So my two questions are:

1)Will the new software encourage a multi-movement work to be a single file from the outset with the ability of laying it all out correctly at the end of the process?

2) Will instrumentation that is different be allowed within the file. I have always used the end of Britten’s War Requiem as an example where the composer goes into 52 staves for the mass effect at the end. If you tried to create this in Sibelius you would have to have those 52 staves throughout the movement/work, slowing down the process by making copying and pasting hazardous throughout. as pasting in Sibelius reintroduces all the hidden staves within the pasting group.

One additional but related question:

Can you force the pagination in the new program always to finish at the end of a page? At the moment I’m often left with a half completed page at the end if it’s work with only a few staves. This forces me to go through the pages manually forcing page breaks in appropriate pages to make sure the music goes right to the end of a page.

@Derek: I would say that the approach our application takes towards multi-movement works is in fact radically superior to how most other scoring programs handle these issues, so it will be very convenient to work on a multi-movement work within a single project file in our application. Instrumentation is also very flexible: if you need some instruments to be present in one movement but not in another, you don’t need to worry about things like hiding their empty staves; instead, you can simply tell the application not to include them until the movement in which they are required.

We are just getting started on the vertical layout aspects this week, so some experimentation is still required, but I anticipate that our application will be able to balance the number of systems per page automatically in order to ensure a full final page.

Great

Thank you Daniel. It sounds like a 15 year wish list is finally coming true!

How about changes within a single movement. For instance, in many 20th century orchestra scores there are large subsections with divisi strings.

I’m interested in hearing more about how you plan to handle parts/instruments.

Will it be possible to divide a 1st violin part into two divisi staves for a few bars, for example? (the “solution” of having the second stave all the time, and hiding it everywhere except a few bars is cumbersome)

Will there be a solution to the problem of automatically extracting “oboe 1 and “oboe 2” from a combined “oboe 1+2” in the score? Automatic detection of things like “a 2” and “unis.”

@Ian: I can’t talk too much about these aspects at the moment, but we are working to make the handling of requirements such as needing to have more or fewer staves for a given instrument in either a score or part layout as flexible as possible. I’ll definitely be able to go into more detail about this later on, as we get nearer to release.

Great – thanks!

I am not sure how complex this is in terms of development, but I found it the one most frustrating missing feature from both Finale and Sibelius: the ability to properly create parts for winds (in a typical orchestral score, where 1st and 2nd share staves). What we have to do today is: finalise our score for printing; then create additional staves for each wind part that shares staff with another in the original score, then extract each voice from the original part (making sure the relevant dynamic, expression, technique and articulation gets correctly copied), so that every individual instrument has their own staff, then create a “full score” part that only has staves with pairs of winds (rather than individual staves), but since this “full score” part isn’t an ordinary part, we need to manually override some of the house style settings (instrument names, multi-rests, bar numbering, etc)… And if you’re working with a theatrical production, and there are changes along the way, then the whole process is repeated (first delete all those individual instrument staves, extract the parts again from the original staves, etc, etc). The ability of Sibelius to automatically update parts whenever we make changes in the score is the most significant time-saver, but with a typical symphony orchestra (where all winds are two per staff), that feature only helps for strings and percussion.

When the score is properly written, an experienced copyist will always know exactly how to extract parts (i.e. where single lines are solo 1st, 2nd or a2). In vast majority of situations, there is a clear indication who is to play the single note in a staff. About the only situations where this may not be the case is when a phrase with two parts in harmony passes through a few notes that are in unison, where the orchestrator would normally omit ‘a2’ (especially if it is just one or two notes, and if it happens frequently in the phrase). Some logic could be written into the algorithm that decides what goes into which part, that could determine if the ‘a2’ passage comes right after and before split ones, and perhaps also defining the maximum length of such a2 passage without it needing to be marked as such.

Otherwise, ideal situation would be that user could specify exactly how many parts does the staff contain, and software would then automatically generate those parts the same way Sibelius today generates parts from each staff. In that sense, Sibelius is vastly superior to Finale in that everything remains in one place, and you don’t have to extract parts in order to add cues or make other types of changes to the part layouts. We can assume that the team, being ex-Sibelius, is fully aware of the huge advantage of having parts completely linked to the score.

Bottom line: for my work, the ability to automatically generate multiple parts from a single staff (where required) is the most significant feature missing from literally every existing tool out there, and would be the most valuable time saver. I won’t even pretend to imagine how much development work this would require, but it would be really cool if this feature made its way to the first commercial release.

Hi Daniel,

this all sounds so good and exciting! I’m looking forward to see the first release of this application!

All the best and good luck to you and the team,

Hannes

Hi Daniel,

Thanks a lot for sharing once more some of the behind the scene thinking and processes for the new Steinberg scoring software. Keep up the fantastic work!

My wallet is waiting:-)

Thanks for these insights into the world of notation software programming. It helps me to understand the other programs s bit better. Like many others, I am curious to see what the interface will look like. Those of us who preferred the older versions of Sib’s interface are hopeful. However, I have noticed that most of the younger generation likes the current Sib look. I’m sure this suggestion would cause lots of headaches, but thought I would throw it out there: IF you are deciding between similar interface options to Sib and Finale, what about a simpler ‘old school’ option that can be selected?

I almost hate to suggest it!

Please continue to take your time, Daniel. We all have something serviceable, now we want something better. It is worth the wait.

Jeff

@Jeff: The user interface for our application won’t look very much like either Sibelius or Finale. It won’t use a ribbon user interface, and nor will it use lots of floating palettes of tools. We will of course share more about how the interface will work as we get closer to release.

Here we go again. After about two years of pounding the conference pavement with Finale in Dallas, Texas, and even Adobe Systems at their MAX Conference in Los Angeles, I have yet to hear of any major “breakthroughs,” what have you of a Schenkerian musical notation useful for the music theorist. I have also tried to interest universities in such research, but there is one component missing: money. Who will take the time and effort to do and research such a thing? Where is the ultimate payoff in do-re-mi dollars and sense?

There are possibly a handful of professional music theorists out there who could use such a program, but, from what I see, is useful in university and academic settings. Therefore, there may possibly be a large market for a software program where one may use Schenkerian analysis quickly and effectively for possible use in either homework assignments or in publishable materials such as journal articles, conference papers, and, of course, theses and dissertations.

My request is simple: Can Steinberg or anyone else develop a useful program using the tools and requirements of Schenkerian analysis? For a graphic representation of what a Schenkerian diagram may look like, I suggest a Google image search on the subject. As it stands, music theorists have to “bend,” “tweek,” or “spank” Finale into obeying our wishes for a detailed Schenkerian graph. The man-hours needed to do such a graph is ridiculous! Torture! Any help at the systems development level is need to redesign the software for doing this. Can Steinberg have the foresight to help with this issue? It shouldn’t be that bad, once a simple graphics program for Schenkerian analysis gets up and running.

See a book by Heinrich Schenker, “Five Graphic Analyses,” available from Amazon, etc., by Dover Publications, of how a typical Schenkerian diagram may look. Schenker gave us a powerful tool for music analysis, but he also gave us a computational and notational nightmare in realizing his graphs in computer form almost a century after he died.

Please look into such software development of Schenker diagrams, Steinberg! Thanks!

Bradley, I’ve used Sibelius to do several Schenker graphs. It’s still not what the program is intended to do, but I can usually make it work with limited headaches.

Having said that, Daniel has said that this new program will be much more flexible with regard to rhythm, so I think that’s something that will be of great benefit to Schenker sketches.

An old practice in handwritten music was to add a closing parenthesis (bracket) after key signatures in staves without time signature, in order to visually separate the “signature” from accidentals… I would love to be able to set this as default in my scores. Will your application be able to cope with this?

@Claude: I’m certainly aware of this convention, and I anticipate that we will support it in our application at some point. I can’t promise it will be in the very first version, though!

Cheers!

there will be versions for beta testers?

@lucanor81: We’re still some way off beta testing, and we haven’t yet determined when or how large our beta program will be, but if we have need of volunteers, we’ll be sure to post about it here when the time comes.

Thanks for all of your updates, Daniel! That would be very exciting for folks of different musical backgrounds to be able to beta test and give feedback! Educators, composers, theorists, etc. I would love to be part of that myself as I am a band director.

The score is looking great (there is the already mention F# that I would have to agree to be to close), but the ties are just beautiful, the font, and the balance of all the spacing. This is definitely the child of a labor of love.

Although I wish this could be out tomorrow already, it is amazing to see quality as a main objective in the development of this tool, and a company like Steinberg allowing for this to happen in its own due time. Kudos to Steinberg and to you and your team. Well done.

(ps: On another note, and traveling much further into the future, please take a look at the new licensing subscription forms for Sibelius, and do your best to stay away from things of that sort, or at least keep the old school buying option available simultaneously)

@estroela: Don’t worry, we are committed to making it simple for people to buy our products, and to allowing existing users to decide whether or not to buy an upgrade to a new version based on the merits of the new features and improvements that are included in each version. Steinberg surveyed its customers about whether or not they would welcome subscription pricing, and the answer was a resounding “no thanks.” Our Director of Marketing, Frank Simmerlein, has stated publicly that we intend to abide by our users’ wishes.

Thank the lord!! I suspect that with Sibelius’s new yearly pricing scheme, you are going to eat their lunch! Thanks your commitment Daniel, I truly suspect that we may well be entering a golden age for notation software.

Subscription pricing is bean counter’s wet dream. Constant stream of revenue, without having to think when the next paycheque is going to arrive, allowing developers to work without pressure from bean counters / management to push the next version out in order to meet quarterly numbers projections…

But for customers, it is off-putting and annoying; your subscription lapses and you’re left with a non-working tool. Vast majority of people prefer buying a license upfront and having the tool work for as long as we own it (or the computer it is installed on). The reasons for this are rather obvious.

Thanks for another update!

When I wrote the global optimal line-breaking, I ran it on a 386/40mhz or so, and it was somewhat expensive, but computers have become 100x faster, and I imagine you could use it for interactive scores too. The equivalent problem for text and line breaks is making its way into browsers and mobile phone platforms too, which are quite constrained. (You have to solve O(#bars * #bars-per-system) spacing problems so you may need tricks if you want to handle arbitrarily long scores.)

The real kicker is when you consider vertical spacing too. Since 5 years or so, LilyPond will also consider dynamic signs jutting out of systems, and avoid linebreaks that would align symbols of adjacent systems horizontally, to avoid forcing them too far apart vertically. I’m curious to see if and how you deal with that.

Global optimal line-breaking is possible in interactive scores, as shown in PriMus since over 10 years. PriMus uses Knuth’s (i.e. TeX’s) totalfit-algorithm modified for scores instead of text. One trick, to make this possible in realtime (you can move the margins with the mouse while the score follows and re-breaks instantly), is, that the horizontal collision is taken into account by an equivalent linear operation, making the inverse (stretching vs. fitting) a cheap operation.

Thanks, Daniel, for this as always interesting stuff.

Years ago I’d hoped that Sibelius could invent a method to make articulations independent of the notes to which they are attached: then they could be filtered and copied to other staves as required. For example staccato dots placed on dozens of Vln 1 bars copied to viola, vln 2. Similarly when sections of wind instruments all needed them.

Will that be possible in Steinberg?

And of course looking forward to Steinberg when it’s finished.

This has worked in Sibelius for quite some time now. The plug-in “Copy Articulations and Slures does exactly what you’re asking. It can simultaneously copy to multiple staves with the same rhythm, and if the rhythm is slightly different, ‘fuzzy match’ will try to copy articulations that make musical sense. You can replace whatever destination articulation you already have, or add to what’s already there.

… Hi Daniel – Just hope that you folks know about StaffPad for the MS-tablet platform?!? – Sure looks fine and such an in-put method would make a lot of composers’ & arrangers’ dreams come true – please, consider this or some such front end input-app in your program that I can’t wait to use – that and “a YouTube ready” “Scorch”-like export function to me looks like THE winning package for pros, teachers and amateurs alike. KUTGW (y)

StaffPad: http://apps.microsoft.com/windows/en-us/app/staffpad/ce714f58-1113-4c30-a9a3-f14a0fb5d7ed

@Per: Yes, we’ve been tracking the development of StaffPad for some time. We’re not working on pen input ourselves, but we are definitely open to working with StaffPad in the future, in whatever form makes sense. I meet with David Hearn, the co-creator of StaffPad, regularly, since he’s a fellow Londoner, and I’m sure we’ll be able to figure something out once we have more of our own application built.

I don’t know… The hand-written music note input looks cool, but is it really efficient…? I spent some 15 years of music education writing music by hand (70’s and early 80’s), finishing it off with 18-stave staff paper, ruler and pencil, large orchestra scores, but by the late 80’s early 90’s, I was already using C-Lab’s Notator. Not even after almost 20 years of writing music by hand (last five of those doing it for a living, almost every day), was I ever as fast writing music down as I was even in the early years of the Notator. After a few weeks (actually, days) of learning one’s way around the QWERTY keyboard, I was much faster than I could every be with pencil and staff paper. Anyway, there may be people who simply can’t be bothered to practice fast keyboard-based input, and for them, stylus-on-screen might be more efficient.

My other concern is Windows Surface; the current addressable market for that device is rather negligible (about 5% of the global tablet market; even smaller among musicians). As intriguing as the initiative is, I’m not sure it is a good investment of development resources for such a small segment of the potential market space. Addressing Android and iOS would be a logical first choice, if one were to pursue pen-based input.

Thanks for the update, Daniel! I imagine the focus of your team right now is to make the program able to produce scores written in traditional notation but what about non-traditional notation? Will you address that in the future? This pertains not only contemporary music but some late-romantic composers as well, like Strauss. My copy of Elektra, for example, shows up to three different time signatures being used at the same time. And what about more contemporary scores like some of Ligeti’s works? He often wrote for several instruments using not only different time signatures but also different tempi and despite that, all the parts line up vertically. Do you think your program will eventually be able to produce such scores?

@Antonio: Our application is already capable of notating some pretty non-traditional notation, including using arbitrary divisions of the octave to produce custom key signatures and accidental systems, open time signatures, time signatures with non-power of two denominators, arbitrarily nested tuplets, and so on, and so on. The intention is certainly to be able to handle the repertoire from the 20th century that still uses more or less conventional notation (which only really rules out fully graphical scores, or very elaborate pieces that mix conventional notation with unorthodox form factors, e.g. Crumb). It may take us some time to get there, but the foundations of the application are designed to be flexible enough to accommodate this music.

I just heard about this project last week and since then have become deeply interested, as my dissatisfaction with existing notation software is an ongoing constant feeling.

It is hard to reach the point in the blog where you guys are on the developing, but I was looking for a specific UI element, for it is what makes Sibelius unusable to me: it’s how you edit notes’ durations after they’ve already been entered. In Finale if you write say two quarter notes and later decide you wanted a dotted quarter note followed by an eighth note you could go back and change it and the remaining notes would be moved in time accordingly until the end of the measure in question, which I think is ideal, whereas in Sibelius you have to rewrite what comes after. It is a design decision and to me it’s a deal breaker concerning Sibelius. I found somewhere among your posts that when the user selects a note and deletes it, the application leaves a rest in its place”, which makes me assume that it will behave similarly as Sibelius. did I understand correctly? If so, I think you could survey your potential customers about it, for I’ve seen many people complain and many people defend this particular thing in some forums, notably the Musescore forum. Each party says the other party’s way of thinking/working is awkward. The ideal solution, IMHO, would be to make it possible to choose which form of handling this the user prefers, but I understand it could be too complex.

So my question is very simple: will it really be like Sibelius in this regard? Where you said this you said too “at least for now” or something similar.

Apart from that, it’s great to see that a software that could be such a fundamental part of our working routing is being handled with such attention and dedication.

@Frederico: You will be able to choose how this kind of situation is handled: the application will always maintain the correct number of beats in the bar according to the prevailing time signature, but you can choose whether or not to shunt notes left or right by the difference in duration produced by your edit, or to replace any leftover duration with a rest, as you wish. The flexibility of input and editing in our application will, I believe, be unparalleled by any other scoring program out there today.

Great! That is, by far, the best solution I could think of and it makes me even more anxious to see the program come out. I’m ooking forward to it and following the development with a lot of interest.

I enjoyed reading the article and seeing the examples you presented. Thank you for sharing.

Dan-

I’ve long been frustrated with a lack of custom viewing in the notation world. Cubase has brilliantly allowed for visibility controls. I’d like to only view strings, or only view instruments playing a certain phrase. Do you guys plan to allow for such track-specific visibility controls?

Also, are you designing your application to be a 1-time transition tool between Cubase and makingnotes, or will I easily be able to go back and forth? I’d like to input in the scoring application, tweak some performances and some other edits in Cubase, then switch back to makingnotes. Will that be friendly? There is nothing more I hate then having a nice performance in the piano roll that is timed just right, then having to do a long clean up to get it to look right in the scoring app. Then, when film edit nightmares strike and I have to revisit a measure, I have to start all over and do all the clean up work again. I just want to know if you guys plan to address these issues or not? I’m not exclusively scoring for acoustic instruments. So I need a scoring application that will not only handle decent page display, but a good musical performance and some dang good clean up options that will allow for changes later in both applications with ease. I can’t afford to be re-working cubase-to-makingnotes file transitions. I hope that my question is clear.

Thank you for the updates. This is a thrill ride!

@Jackson: We know that the workflow of going between your DAW and your scoring program can be painful and time-consuming, and we certainly have some ideas about how we can make this workflow more efficient. We won’t have deep, direct integration with Cubase in our first version (this requires a lot of time and effort to be expended both by us in London and by our colleagues in Hamburg, who are focused on the extraction of the audio engine from Cubase for use in our application at the moment), but that is what we will build towards as our application matures.

Hi Daniel,

I don’t know if it will make any difference as I have no expertise in engraving music, but when I look at the output from your program it really doesn’t look right to me (compared to the Edition Peters version for example) and gives me a jarring feeling. I know I will be able to adjust things but but I feel I would have to adjust a lot. I feel sad about this as I love the approach you are taking to thinking ground up about these things.

If it would help, I’d be happy to give a list of the things that don’t look right to me.

In any case, I wish you and the team good luck with the remaining development and testing work!

best wishes

Rich

@Rich: Please do give me a list. I’d be interested in your feedback. Probably best if you drop me an email.

I’ve been tracking this development since the beginning, and it seems more worth the wait with each development diary entry. Thank you for your work!

No one else seems to have mentioned this yet, but in the image with 6 products compared, it seems clear to me that the Edition Peters is the most natural, and I find the linked PDF of Fugue 16 to be quite beautiful, well spaced, and easy to read.

Why does Steinberg’s put 4 bars in the first system, and only 2 in the 3rd system of the 2nd page? Is it that much better? Does the algorithm need tweaking, or will it be left that way? Obviously, I’m guessing this will be very easy to adjust in a second, but if it can be done automatically, all the better!

@Keehun: Our application puts four bars in the first system because they fit! Without going into too many details about how it all works, the basic approach is to try to put as much music as will fit on each system to start with, and then deal with any ugly remainder (e.g. having only one bar left on the final system, or something like that) by working backwards. There are other approaches to solving the problem, and we certainly haven’t ruled out trying other approaches. Our goal is always to produce results that require the least amount of tweaking and changing, and getting towards the kind of consistency of flow and spacing in the Peters engraving is definitely a desirable outcome for us.

I was wondering the same thing about your output, and one thing I’ve thought about is the visual rhythm of the layout. I approach this as a performer more than an engraver, since I find that pages that are laid out with slightly more regular bar lengths are just that much easier to read. (That said, I certainly don’t want bar lines that just line up straight down the page!) It seems that there should be a way for the application to look at its “best fit” solution and recognize when the rhythm of bar numbers per line is stuttering, as it were, and make an effort to even things out.

Hi, Dan. You care to discuss this,

https://www.w3.org/community/music-notation/

And how it relates to the new application?

@Frikandel: You can read about this move in more detail on the SMuFL web site. It doesn’t change anything in the short term for us: we were obviously going to support SMuFL in our application, and we are also going to support MusicXML. However, we are excited about where this could take both the SMuFL and MusicXML standards in the future!

Recently, I have been pondering what the future implementation of 3rd party sample libraries might look like with Steinberg’s Notation program. I am speaking of string libraries that use C0, C#0, D0, etc. to create articulation changes such as arco, pizz, tremolo, trill, etc. Without giving away too much information, are you free to share if there will be a way to do this without having to use additional sound set templates from yet another 3rd party app? I am really trying to imagine the most elegant and efficient way to achieve this!

@Dave: We will be using as much of the infrastructure in Cubase for handling this, known as VST Expression Maps, as possible in our application. You can read a little bit about them here on the Cubase product pages, and there is lots more information about how they work in Cubase in its Operation Manual, which you can download here if you want to find out more. We will probably have to extend the VST Expression Maps concept slightly to support a wider range of playing techniques and articulations, but we are hoping to do this in a manner that retains compatibility with VST Expression Maps that have already been produced for Cubase.

How about Note Expression?

When will you publish demo or beta edition of this application ?

@ercan: We have no news about this to share at the moment. Please keep following the blog for more updates.

Will we able to use plug-in (like Sibelius)?

@ercan: Yes, ultimately our application will support running user-created scripts written in Lua.

Will we able to control between accords 5th-8th? (i think “yes”)

Sorry for my english. Not “accords” it is “chords”.

Okay, we’re well into September now, so it must be time for another update—with a surprise Holiday Season release date! 😉

@James: I will start work on another blog post at some point in the next couple of weeks. There continues to be a lot going on, of course, and it can be a challenge to carve out the time to write about it in detail.

Well, increasing constraints on your time can only be a good sign, I think. So, we’ll survive!

And as thought #100 on this subject: Am I really the first one to note that the layout as drawn by Daniel of product C’s layout only has 32 bars, not 34?

I understand this entry is about system organization, but since several spacing problems shown in your product’s rendering of BWV 861 bars 29-31 were not mentioned, I feel compelled to point them out (at least those that leap out at me).

(1) Bar 29 after the key signature there needs to be a bit of space (compare with Peters). Steinberg’s rendering is too crowded; the tenor F-sharp almost clashes with the signature’s E-flat.

(2) Also in bar 29, note heads need to be more closely aligned on the “&s” of beats 1 and 2 in the soprano and alto voice crossing (again compare with Peters). Steinberg’s rendering is putting too much space there so that the rhythm is a bit distorted. The soprano note heads should be only a hair away from the (crossed) alto stems.

(3) In bar 30, the soprano F-natural accidental is too close to the E stem directly previous.

(4) At the end of each measure there should be a bit of space; the last notes are just a bit too close to the end of each bar.

Very glad to see you’re taking on rendering issues specific to contrapuntal music! Thank you so much for all your excellent work!

@Aaron: You can take a look at an updated rendering of how those bars look in a more recent build of our application. The issues you describe with regard to the spacing of accidentals versus key signatures and versus the preceding rhythmic positions have been addressed. If you would prefer more space at the end of the bar, or less space between interlocking voices, you can tweak this in the application’s engraving options.

@Daniel: Now that looks SO much better than the original in this post. I’m wondering, though, if you could show how the spacing reacts to changing the system width to be the same as the original Peter’s edition? The updated one is about half a measure wider than it. Here’s what I mean (I tried to make the staff-height as identical as possible for accurate comparison): Before & After comparison.

I’m afraid my opinion hasn’t changed, however, as @Aaron pointed out in (2). I still think the noteheads of the crossed voices in m. 29 is still too far apart (though I know you mentioned that I can change that setting). I just think it would look much better by default if the offset one were closer to the primary note column to make the rhythm. It would just make it that much clearer.

Please tell your developers they are doing great work! Very exciting peek.

@Daniel, thanks so much for considering my comments and responding with the updated rendering! It looks much better; however, the crossed voices still leap out as wrong. I understand what you wrote “If you would prefer … less space between interlocking voices, you can tweak this in the application’s engraving options” which is reasonable and I’m glad it is something that can be tweaked, but the application by default should render crossed voices in polyphony according to the following aim: align the note heads as closely as possible without touching stems or flags. The best engraved scores of contrapuntal keyboard music all use this principle. It is very important also when multiple parts create “chords” that need to be notated with independent stems. The voices cascade according to the principle – note heads aligned as closely as possible without touching stems or clashing flags.

@Aaron: The gaps that we’re using are pretty consistent with Gould’s recommendations in Behind Bars (see pages 53–54), so I feel good about them as they stand. Of course many aspects of music engraving are matters of taste, and it will be easy to adjust these gaps in such a way that all of your projects will use your preferred settings without needing to make the same adjustment in each one.

Re-reading this, I had some thoughts/ideas about a new approach to rhythmic spacing / casting off.

The Edition Peters layout is clearly the best, with three bars per system except for one system. Why do I think it’s the best?

The piece has a consistent tempo and most bars consist of semi-quaver or quaver material. The performer benefits from each bar being of a reasonably consistent size. The imaginary moving playback line (or Disney “bouncing ball”) moves at similar speed in each bar. A performer would find rapid changes in its speed to be subconsciously jarring.

I wonder if a casting off algorithm could calculate the speed of the playback line in each bar, and minimise how this would vary over time, perhaps by calculating a standard deviation. The algorithm could compare this value between different casting off choices and use this as a factor in its decisions.

I realise taking these ideas to their logical conclusion might result in every bar being the same size, which would not be ideal. The algorithm would need some weighting that took into account the resulting optical and rhythmic density.

Just a thought.

Ian (programmer and musician)

@Ian: I’d need to think about your idea in more detail to be sure, but off the top of my head, the problem with a spacing algorithm that is based around keeping the speed of a playback line more or less constant is that it would tend towards proportionality, which is actually pretty undesirable in music spacing (except for music which is intended to be spaced fully proportionally, which while not uncommon in the latter half of the 20th century is still something of an exception).

Hi Daniel, I’m not suggesting that the speed of the playback line should be more or less constant, just that using its speed as a factor in the casting off algorithm might improve things.

Check out the latest sibeliusblog.com, “Daniel Spreadbury previews Steinberg software in New York.” Go to http://www.sibeliusblog.com/news/daniel-spreadbury-previews-steinberg-software-in-new-york/

I think first version is ready for start-come out. 🙂

If Daniel only could find time to tell us something about something… 🙂

Development diary, part 11, was published 29 June 2015. I so hope this means NEWS. 🙂

http://www.sibeliusblog.com/news/staffpad-for-windows-10-released-with-new-features/

What has this StaffPad advertisement got to do with Steinberg’s notation program to come and why is it here on Daniel’s great blog? Stupid and vulgar.

pls be respectful. 🙁

Exactly. That’s what I ask you to be and not to post spam here. Thank you.

“Be close to your friend , be closer to your enemy.” Sun Tzu.

This might sound like a grocery list item, but I’ll give it a shot. I’m working with Musescore 2.0.2 and for me, it is fine so far. I am sort of a beginner in writing music. But I might change for a new software in the near future. I am a guitarist and I use also guitar diagrams for my scores. I find these diagrams very limited and static. When I move a finger in a chord, make a pull-off or an hammer on, I have to ad a diagram for each event, which make the score scrambled with guitar diagrams. How about animated and dynamic guitar diagrams in your sofware which reflect minor changes in the guitar playing while performing a chord? Do you thing that this is possible? That would be so cool.

I’m thinking how nice it would be to have a split view, or two parallel galley views of the same piece so that things can be compared or copy and pasted from measures 41-49 to measures 134-142. Music is very pattern based, and repetition based. Working on more than one point in the score at the same time would be very beneficial.

Another feature I’d give most anything for would be direct native Roman Numeral figured bass notation (I’d be happy to enter it myself (automatic would be insane).).

@Jim: You can create a split view by way of Window > Split Horizontally, and then open the same layout in both halves of the split if you wish, so this kind of thing will be easily possible in Dorico. No Roman numeral symbols as yet, I’m afraid, but when we start working on chord symbols we will consider whether or not we can also implement Roman numerals, and possible function symbols, at the same time.